One of the most common stereotypes about human life is that men hunted and women gathered. Some genders of labor, as the story goes, would have provided humans with the meat and plant foods needed to survive.

That characterization of our time as a species entirely dependent on wild foods – before humans began to domesticate plants and animals more than 10,000 years ago – is consistent with the pattern anthropologists have observed among hunter-gatherers during the 19th century and early 20th century. Almost all of the big game hunts they documented were done by men.

It is an open question whether these ethnographic accounts of labor are truly representative of the subsistence behavior of recent forager-gatherers. They certainly inspired the assumptions that some genders of labor arose early in the evolution of our species. Current employment statistics do little to shake that idea; in a recent analysis, only 13% of hunters, fishermen and trappers in the US were women.

Still, as an archaeologist, I have spent much of my life studying how people in the past got their food. I can’t always square my views with the “man the hunter” stereotype.

A long-standing anthropological assumption

First, I would like to note that this article uses “women” to describe people who are biologically equipped to experience pregnancy, while recognizing that not all a person who identifies as a woman is equipped as such, and not all people who are equipped as such identify as women.

I am using this definition here because reproduction is at the heart of many hypotheses about when and why subsistence labor became a gendered activity. As the thinking goes, women gathered because it was a low-risk way to provide a reliable stream of nutrients to dependent children. Men hunted to supplement the family diet or to use hard-to-find meat as a way to attract friends.

One of the things that has troubled me about attempts to test related hypotheses using archaeological data – including some of my own – is that plants and animals are assumed to be mutually exclusive food categories. Everything hinges on the idea that plants and animals are completely different in terms of how dangerous they are to find, their nutrient profiles and their abundance on a landscape.

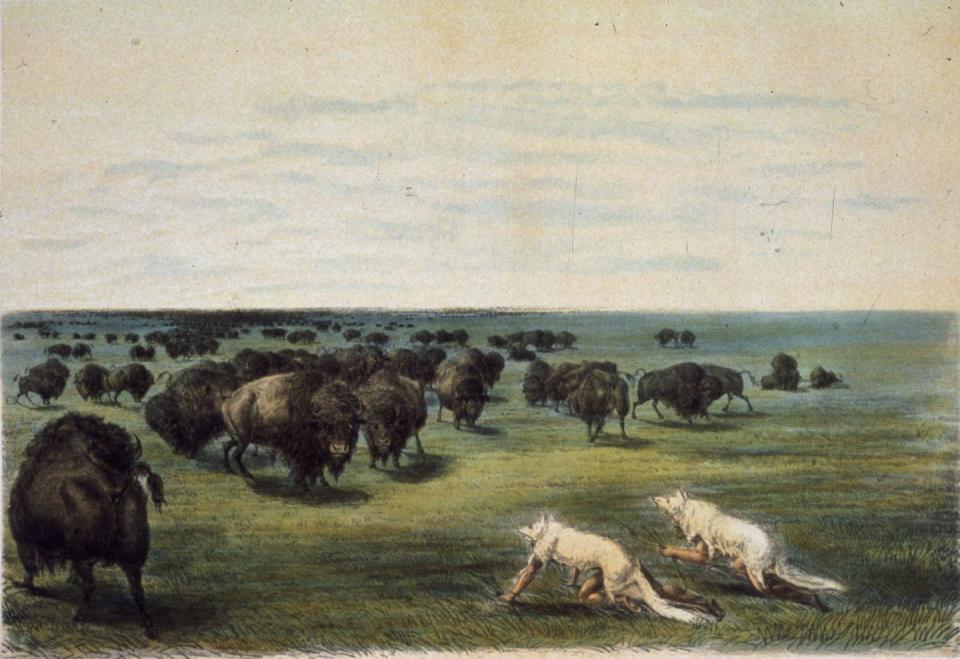

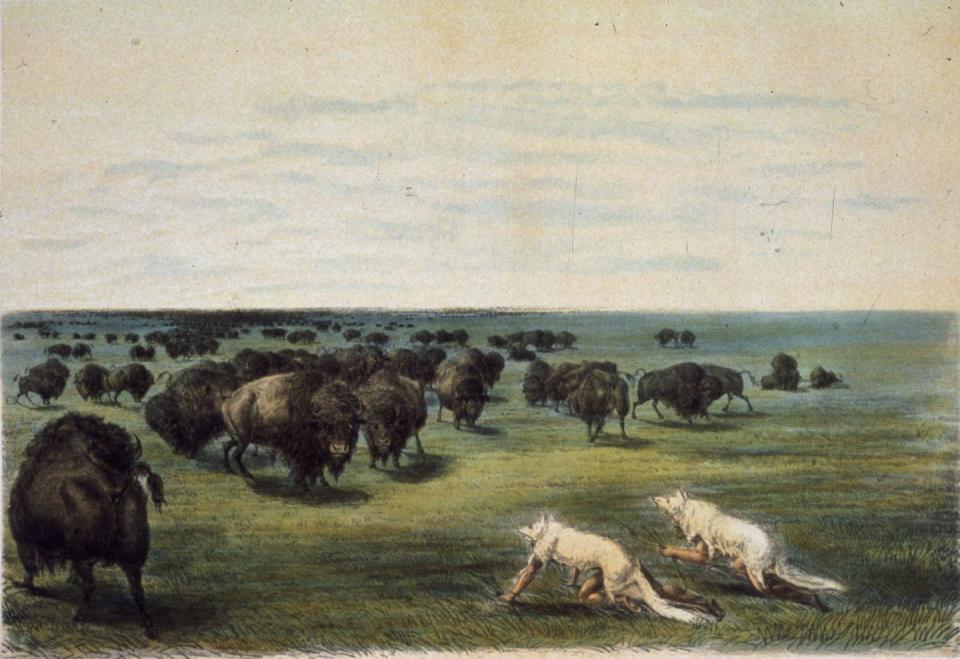

It is true that highly mobile herbivorous species such as bison, caribou and guanaco (a deer-sized South American herbivore) were sometimes concentrated in places or seasons where human edible plants were scarce. But what if people could get the plant part of their diets from the animals themselves?

Animal prey as a plant-based food source

The plant material being digested in the stomachs and large intestines of ruminants is a less palatable substance called digesta. This partially digested material is edible for humans and rich in carbohydrates, which animal tissues lack.

Conversely, animal tissues are rich in protein and, in some seasons, fats – nutrients that are not available in many plants or occur in such small amounts that one would need to eat only modest amounts to meet nutritional needs. meet daily plant only.

If people in the past ate digesta, a large herbivore with a full belly would essentially be one-stop shopping for complete nutrition.

To explore the potential and implications of digestion as a source of carbohydrates, I recently compared institutional feeding guidelines and human feeding days per animal using a 1,000-pound (450-kilogram) bison as a model. First I compiled estimates available for protein in bison’s own tissues and carbohydrates in digestion. Using that data, I found that a group of 25 adults could meet the US Department of Agriculture’s recommended daily average for protein and carbohydrates for three full days eating buffalo meat and digestifs from one animal.

Among humans in the past, the consumption of digesta would have driven the demand for fresh plant foods, potentially changing the dynamics of subsistence labor.

Recalibrate the risk if everyone is hunting

One of the risks usually associated with big game hunting is failure. According to the evolutionary hypotheses regarding the gender division of labor, when the risk of hunting failure is high – that is, the probability of bagging an animal on any given hunting trip is low – women should have more reliable resources choose to provide children, even if it means long meeting hours. The cost of failure is too high to do otherwise.

However, there is evidence to suggest that large game was much more abundant in North America, for example, before the 19th and 20th centuries ethnographers noted foraging behaviors. If high-yield resources such as buffalo could be obtained with low risk, and the animals’ digestion was also consumed, women may have been more likely to participate in the hunt. Under these circumstances, hunting may have provided complete nutrition, eliminating the need to obtain protein and carbohydrates from separate sources that may have been widely distributed across the landscape.

And, statistically, women’s participation in the hunt would help reduce the risk of failure. My models show that if all 25 people in a hypothetical group took part in the hunt, except for the men, and all agreed to share when they succeeded, each hunter would only have to be successful about for five times a year for. a group subsisting entirely on buffalo and digesta. Of course, the real world is more complicated than the model suggests, but the exercise shows the potential advantages of digestion and female hunting.

Ethnographically documented consumption of digesta is common for hunters, especially where herbivores were plentiful but edible plants were scarce, such as in the Arctic, where prey stomach contents were an important source of carbohydrates.

I believe that eating digesta may have been a more common practice in the past, but direct evidence is extremely difficult to find. In at least one case, plant species present in the mineralized plaque of Neanderthal human teeth point to digesta as a source of nutrients. To systematically study past digestive consumption and its aftermath, including female hunting, researchers will need to draw on multiple lines of archaeological evidence and insights gained from models like the ones I have developed.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Raven Garvey, University of Michigan

Read more:

Raven Garvey does not work for, consult with, own shares in, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article this, and has not disclosed any relevant connections beyond their academic appointment.