The floating “magic islands” on Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, may finally have a scientific explanation. Scientists believe they are honeycomb-shaped clumps of glacial snow.

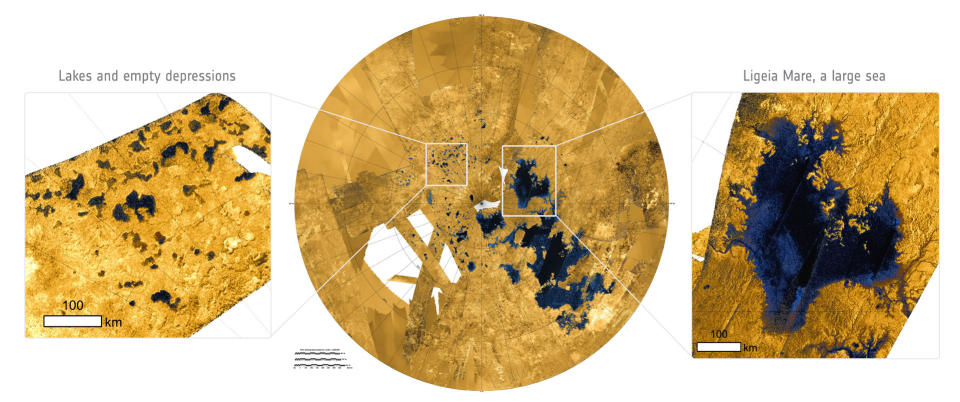

The so-called islands were first spotted by the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft in 2014 while peering through the orange ring around Titan, a moon larger than the planet Mercury. Appearing as shifting bright spots on Saturn’s moon above lakes of liquid methane and ethane, the islands have left scientists scrambling for an explanation. No one could figure out how these ephemeral blocks could appear, then simply disappear, from observation to observation.

However, new research led by Xinting Yu, an assistant professor at the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Texas San Antonio, suggests that these magical islands are actually floating porous organic solids, frozen in shapes not unlike those of a comb. honey or swiss cheese. Presumably, the solids accumulate after snowfall from the Titan sky.

“I wanted to investigate whether the magical islands could be organisms floating on the surface, like pumice that can float on water here on Earth before finally disappearing,” Yu said in a statement.

Related: Nuclear-powered Dragonfly mission to Saturn’s moon Titan delayed until 2028, NASA says

The magical islands of Titan are real after all

Theories developed to explain the magical islands of Titan fall into two broad categories. On the one hand, there are those who suggest that the islands are like a phantom; on the other hand, there are those who say they must be real physical bodies.

In the phantom category are suggestions that the islands could be caused by waves in the moon’s methane or ethane lakes, or perhaps even chains of bubbles associated with floating materials beneath these liquid bodies.

But Yu discovered the peculiar non-phantom nature of the magical island of Titan when she decided to take a closer look at how the moon’s atmosphere, which is 50% thicker than Earth’s and rich in methane and other organic molecules, relates to its lakes liquid. and dark dunes of organic matter across its surface.

Titan’s upper atmosphere is dense with organic molecules that can clump together, freeze, and then snowball onto the moon’s surface and into the calm rivers and lakes of methane and ethane that complete this alien sight.

To see if this could account for magical islands, the team first had to determine whether the complex organic molecules of Titan’s “snow” would immediately dissolve as soon as it hit the liquid lakes and rivers. The researchers concluded that because these liquid bodies are already packed or “saturated” with organic molecules, this dissolution could not occur.

The next question Yu wanted to answer was: What happens to these lumps when they hit these liquid bodies? Would they sink or float?

“For us to see the magic islands, they can only swim for a second and then sink. They have to swim for a while, but not forever, either,” said Yu.

At first glance, the Titan models seem to suggest immediate absorption of the solids. Ethane and methane would have a low surface tension in the liquid regions of Titan’s surface, while the frozen solids would have a high density. This suggests that these frozen materials would not float long enough to be mistaken for islands, magical or otherwise.

But, the team says, there is a mechanism that would enable this snow to float on liquid lakes of methane or ethane.

If the snowpacks were large enough and porous like Swiss cheese, the hollow holes and tubes would allow them to float until methane or ethane escapes inside, filling the voids and causing them to sink.

The model developed by Yu and her colleagues suggested that individual clumps of snow would be too small to allow this to happen, but if enough of this snow converged on the shores of Lake Titan, large pieces could break off and fall off and float. on methane/ethene lakes.

This is similar to how ice sheets break off from glaciers on Earth and float into seas, a process known as “calving.”

RELATED STORIES:

—Saturn’s moon Titan looks strange to Earth, and scientists may finally know why

—Saturn’s largest moon Titan can bake its own atmosphere

—James Webb Space Telescope gives scientists a glimpse of Saturn’s strangest moon Titan

Yu and her fellow researchers also explained another mystery on Titan: why its liquid body is so peaceful with waves no bigger than a few millimeters.

She and the team determined that this is because the surfaces of these liquid bodies are coated with a fine floating blanket of frozen solids that gives them their smoothness.

The team’s research was published on Thursday (January 4) in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.