It was Sunday, December 12, 1992, just a week or so before he was due to go to Mustique for the holidays. David Bowie was 45, and he was in a promo for his 18th album, Black Tie White Noise, which would be released in a few months.

He was feeling his way around a few photographers, seeing how it felt to re-enter the market after a few years of messing around with his boy band Tin Machine, a project that looked more than ever like an agent’s fantasy extremely biased estates. He was married to Iman for six months, and his enthusiasm to make music again with renewed energy was a big part of it.

He was, basically, happy.

Bowie arrived at Metro Studios in Clerkenwell accompanied, as ever, by his long-time assistant, Coco. She was everything to him, as he was everything to her. She was soft and hard, nice and tough, short and indulgent, whatever took her fancy. Today she was all Gile, as was her charge twice. Smile, laugh, eager to get on with the day.

Kevin Davies was the photographer, the least exposed of his kind, and yet a man who had established relationships with all the important magazines of the time: iD, The Face, Arena, The Sunday Times Magazine and Vogue. Bowie immediately welcomed him, and the results of that meeting now form the basis of an exhibition opening next month at Fitzrovia Chapel, just north of Oxford Street.

They arrived that morning, photographer and subject, at the studio almost at the same time, and proceeded to plot and plan the day in the most orderly manner.

Bowie was curious, talkative, and eager to see where the shoot was going. For 25 years he directed photographers, allowing them to direct him, and he had an almost co-dependent relationship with his image, but, almost unbelievably, he was softening.

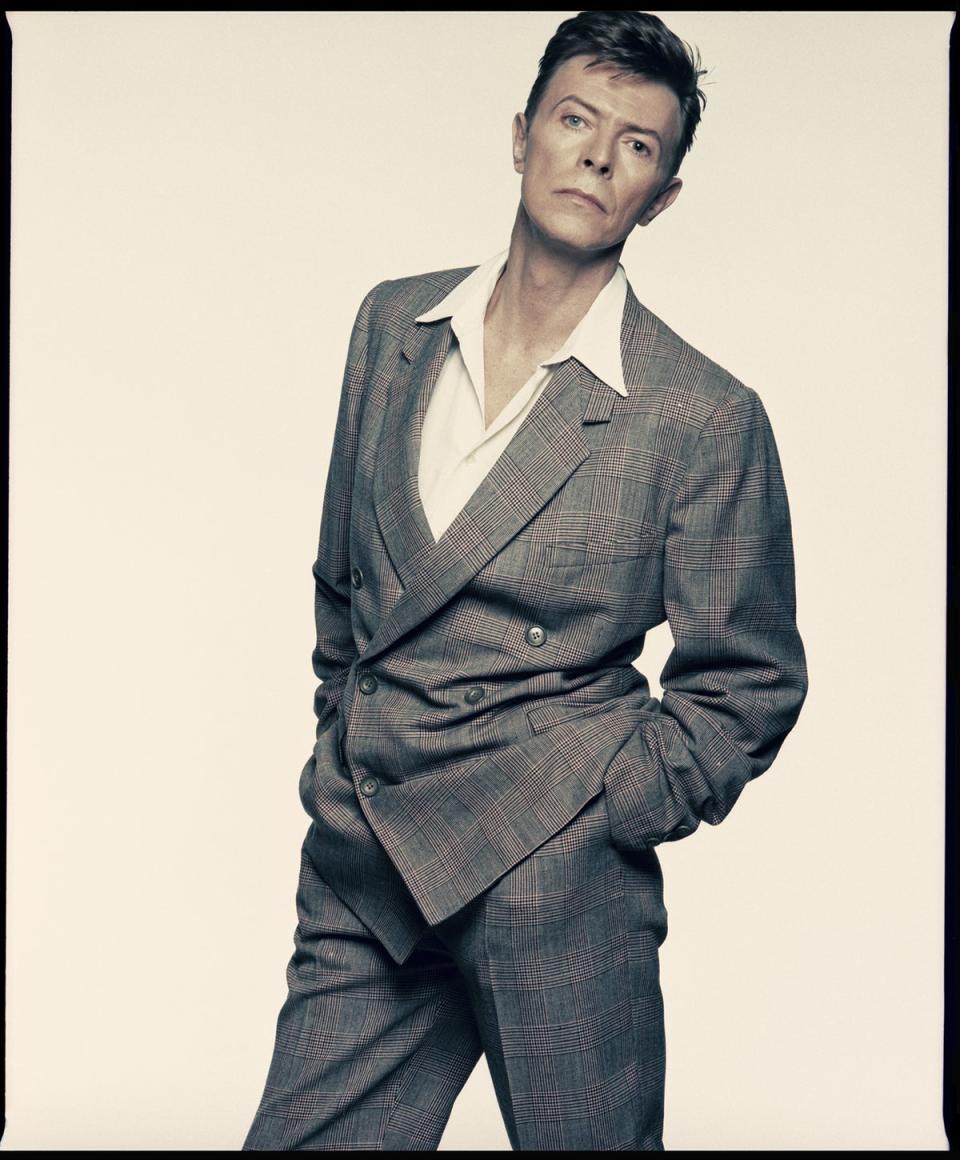

He was not going to erase Tin Machine’s memory by an extremely volte face, but by a moderate development. And so he was, exchanging Polaroids with Davies, and enjoying the box of Bond Street clothes that now littered the studio floor.

Between shots he would take breaks in the dressing room. Kevin’s interpretation was that he needed moments of privacy to feel comfortable in front of the camera. At lunch Bowie was talking enthusiastically with hair and makeup about the music they were listening to and the clubs they were going to. He was very friendly and engaged with everyone on the shoot.

However, he surprised Kevin with his cunning and the mental nature of his behavior – but then he was certainly mirroring Davies’ own way of working.

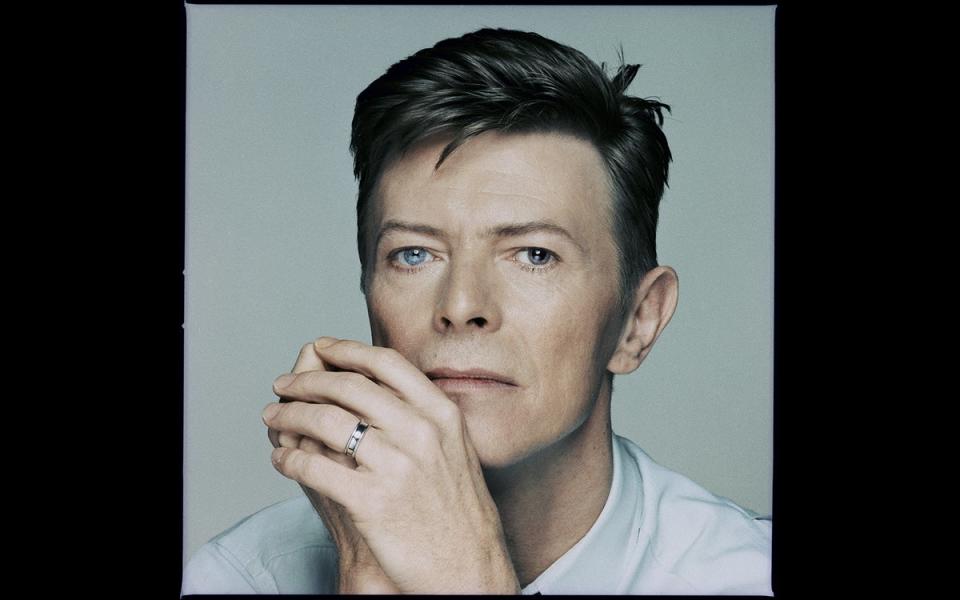

During the shoot he was warm and open to ideas, down to earth and easy to work with. He was interested in collaboration, especially towards the end of the day when he was completely relaxed, which led to some of the more intimate portraits they took, many of which are on display in this exhibition. Football probably had the opposite theme to most sessions like this at the time; The objective was to promote an idea using as much diversity as possible. So this was a very special London day.

Bowie later allowed a selection of Davies’ images to be used in the press, after which Kevin put the original rolls of film, contact sheets and prints into storage where they remained for almost 30 years. In 2020, during the lockdown, Davies uncovered the boxes, to reveal perfectly preserved film negatives of over 400 images from that day alone with Bowie, whose details were encapsulated by the unrecognizable memory of a luminous presence.

Kevin decided to do something about it, and spent months going through the images, whittling them down to the 24 that will soon be on display in Fitzrovia Church.

“With the anxiety of locking I found comfort in retrieving my career through boxes of stored negatives,” says Davies. “I finally had a chance to do something I’ve been wanting to do for a long time; rediscover past jobs in their entirety. For me, this exhibition is an opportunity to show the photographic process beyond a commission.

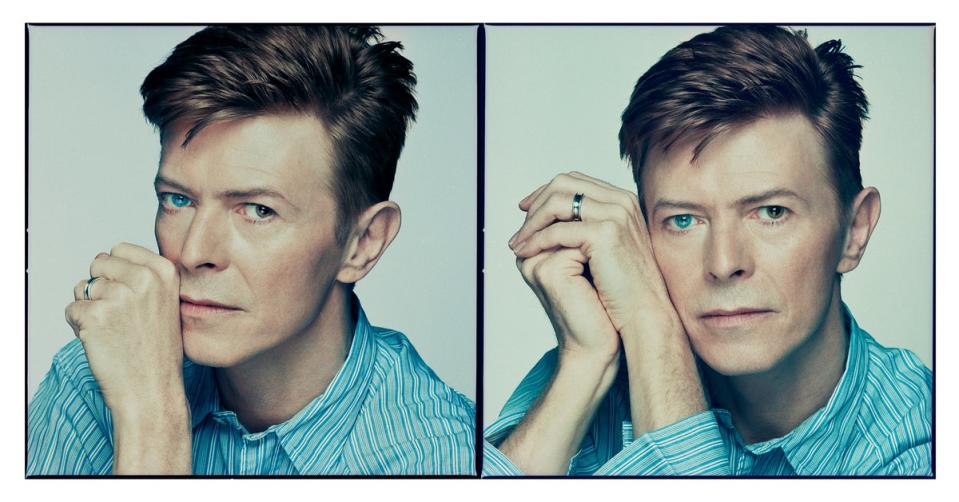

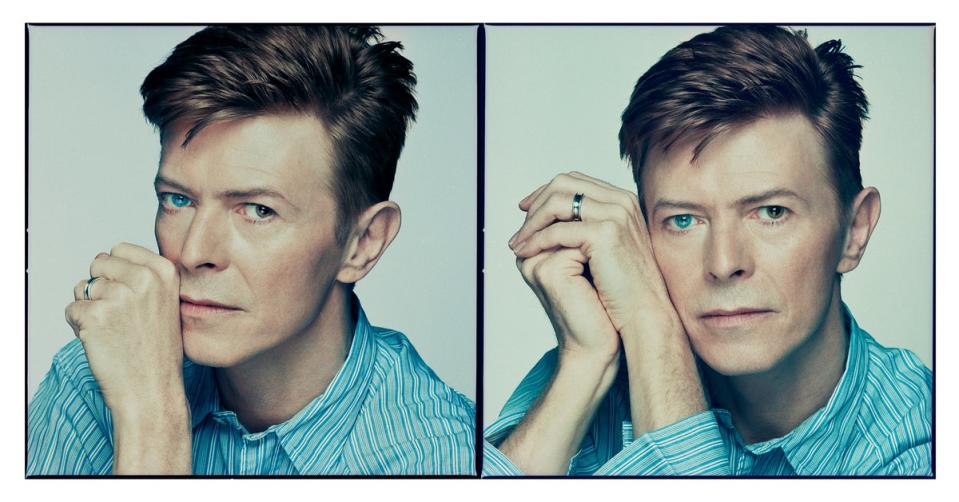

“Some of the images are in diptychs and triptychs, inspired by Richard Avedon. I wanted to convey progress in the shoot and show the subtle differences between frames. It was a process of reconciling his original preferences with mine.”

While making his choices, Kevin asked me to help curate the exhibit, which was one of the nicest offers I’ve had in a while. Who wouldn’t want to curate a Bowie exhibition? I have always enjoyed working with Kevin, especially his attention to detail.

“The color of the images was the result of my long relationship with my printer Brian Dowling, who printed the original prints in 1992,” says Davies. “I also wanted to rework the images, which might not work with every rock star but with Bowie.

“I have a very clear memory of looking through the viewfinder and thinking, ‘it’s David f***ing Bowie, don’t f*** this up.’

“What did we talk about? They both settled.”

The exhibition takes Bowie as the subject of the exhibition, but it is also a reflection of the other world of analogue photography. It explores the intersection of the archive and creative memory.

This is a fascinating work because it is a visual story that takes place over one session in one day. It not only shows Bowie’s unusual attention to detail, but also Davies’ ability to shape and catalog that story.

Madeleine Boomgaarden, director of Fitzrovia Chapel, says, “These quiet and very beautiful images of Bowie sit perfectly in the calm beauty of the chapel. We are delighted to host images of this London icon in the heart of the city where he grew up.”

She is right. And I guarantee that it will be a spiritual experience for everyone who comes.

David Bowie – A London Day by Kevin Davies is at Fitzrovia Church from March 1 to 20; fitzroviachapel.org.uk