-

Lise Meitner recognized the process of fission when her male colleagues could not figure it out.

-

Her closest colleague, Otto Hahn, described her significant role in the discovery.

-

In 1944, Hahn won the Nobel prize for the discovery. Meitner was nominated but did not win.

The discovery of nuclear fission was one of the greatest scientific milestones of the 20th century. It was the cause of the atomic bombnuclear power, and the Nobel Prize in 1944 for the German chemist Otto Hahn.

But Lise Meitner, Hahn’s longtime colleague and collaborator who identified and scientifically explained the process of nuclear fission, was nominated for a degree. Nobel the same year but did not win.

“Every physicist knew that was her work and she deserved that award,” Marissa Moss, a biographer of Meitner’s, told Business Insider, adding that she thinks it was the reason Meitner was overlooked. than the issue of sexism and antisemitism.

“I think it’s very easy to dismiss a Jewish woman,” Moss said.

Meitner was admired by other physicists — Einstein called her “Our Marie Curie” — comparing her to the two-time Nobel laureate.

During her career, Meitner was nominated for the Nobel Prize 49 times without winning, but the 1944 award is the most significant of her brilliant career.

Meitner had to flee Nazi Germany

Meitner, Jewish and born in Austria, was the first professor of physics in Germany.

She headed the radiophysics division at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin. Hahn was head of radiochemistry and would later become director of the institute. They often collaborated over the years, including the joint discovery of the element protactinium in the late 1910s.

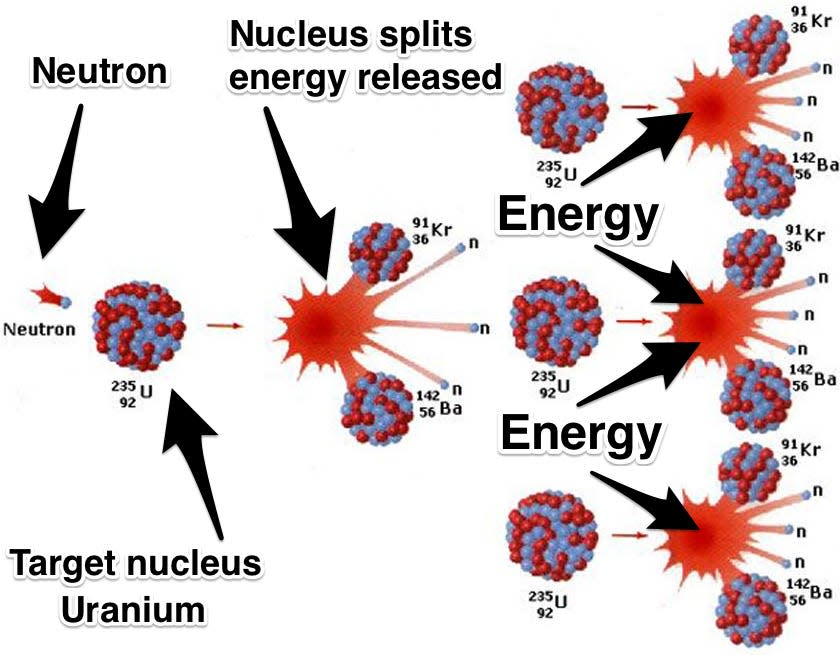

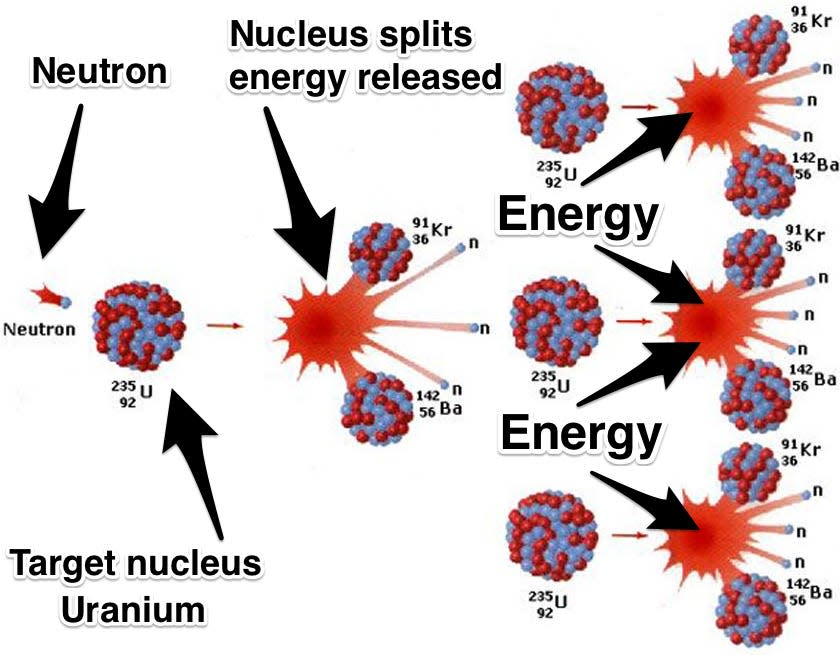

In the 1930s, their work together continued to investigate transuranic elements. The idea was that new, heavier elements called transuranics could be produced by bombarding uranium with neutrons.

But as Hitler came to power, Meitner’s position became tenuous; she lost her professorship in 1933, and was only allowed to stay in Berlin because of her Austrian citizenship. After Germany was annexed by Austria in 1938, Meitner fled to Sweden.

“All her Jewish colleagues left years before she did. She continued because she had a community, and she could work,” Moss said.

Meitner, who was in exile in Sweden, kept up a correspondence with Hahn. At Meitner’s urging, he and the chemist Fritz Strassman continued their experiments with uranium. Then, in December 1938, she received a letter from Hahn detailing an obscure experimental result.

Hahn discovered fission but wasn’t sure about it

Hahn’s letter stated that their experiments to bombard uranium with neutrons appeared to produce barium as a product. There was no ready explanation for this result because barium is a much lighter element than uranium, and scientists expected to produce heavier elements, not lighter ones.

Hahn wrote to Meitner: “Perhaps you can come up with some wonderful explanation. We ourselves know that it cannot be broken apart in Ba.”

Before Meitner could respond, Hahn and Strassman published their results, but without any explanation of what they thought was happening – and no mention of Meitner’s role in the experiments in their paper.

“You have to understand that he couldn’t really quote Meitner because it didn’t appear that he was working with a Jew,” Moss said. “He was already writing letters to her complaining that he had worked with her while ruining his reputation in the institution. At the big dinners of the institution, he was sitting at smaller tables, he was not getting the ambitions he deserved by him, because he was working with a Jew. and that was not a good thing.”

Meitner continued to ponder Hahn’s findings and, discussing it with his nephew, the physicist Otto Frisch, came to the conclusion that if an atomic nucleus were imagined as a liquid drop, perhaps energetic neutrons could split the uranium nucleus into produce different parts and lighter elements. — the process of nuclear fission.

Meitner used Einstein’s famous equation E=mc^2 to explain the reaction mathematically: The atoms produced after uranium fission weighed slightly less than the original uranium atoms — and the missing mass was transformed into pure energy.

In February 1939, Meitner and Frisch published their paper on fission in the scientific journal Nature, just one month after Hahn’s paper.

It was not expected for the Nobel Prize

Hahn was awarded the 1944 Nobel Prize in chemistry for the discovery of nuclear fission. Meitner was nominated in the physics category, but did not win despite his crucial role in verifying and explaining the discovery. Strassman and Frisch were also overlooked for Nobel.

An analysis of Nobel committee records published in Physics Today concluded that one reason Meitner was overlooked was “a general failure of the evaluation committees to appreciate the extent to which German persecution of Jews had skewed the published scientific record” .

Since 1901 more than 621 Nobel Prizes have been awarded in the fields of physics, chemistry, medicine, literature, peace and economic sciences. Of those 621 awards, only 65 have gone to women — about 10%.

More than twenty years later, in 1966, Meitner, Strassmann, and Hahn were awarded the Enrico Fermi Prize for their discovery.

But Hahn had spent years downplaying Meitner’s role. She was referred to as her mitarbeiterin in the German press and in a museum display of the apparatus used to detect fission – a word that “can be interpreted as helper,” Moss said.

Hahn did nothing to dispel the notion that Meitner played a small role in the discovery.

“She was very hurt by it,” said Moss.

Read the original article on Business Insider