Some 90s trends are making a welcome comeback; others, no one needs to see again. Unlike frosted tips, baggy Tie-Dye shirts, landline phones and pockets, however, which have (hopefully?) been consigned to the dustbin, binary stars are resurfacing as worth studying. And not a moment too soon.

In short, binary stars are crucial to understanding stellar evolution. They can also contribute to our understanding of exotic astrophysical phenomena, such as the supernova explosions that mark the births of black holes and neutron stars. However, for decades, binary star research has been as neglected as the old Tamagotchi in your drawer.

Kareem El-Badry, a researcher from the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), confirms that a binary star revival is now underway.

“I think many astronomers have been looking at binaries as a kind of solved problem and less exciting than other areas of astrophysics, like galaxy formation, cosmology, or exoplanets,” El-Badry told Space.com. “It’s an old field, so after 200 years of study, it seemed about 15 years ago that most of the important questions were answered. Now binary stars are coming back stronger than the 90s trend !”

Related: Record breakers! Super-compact dwarf stars orbit each other in less than a day

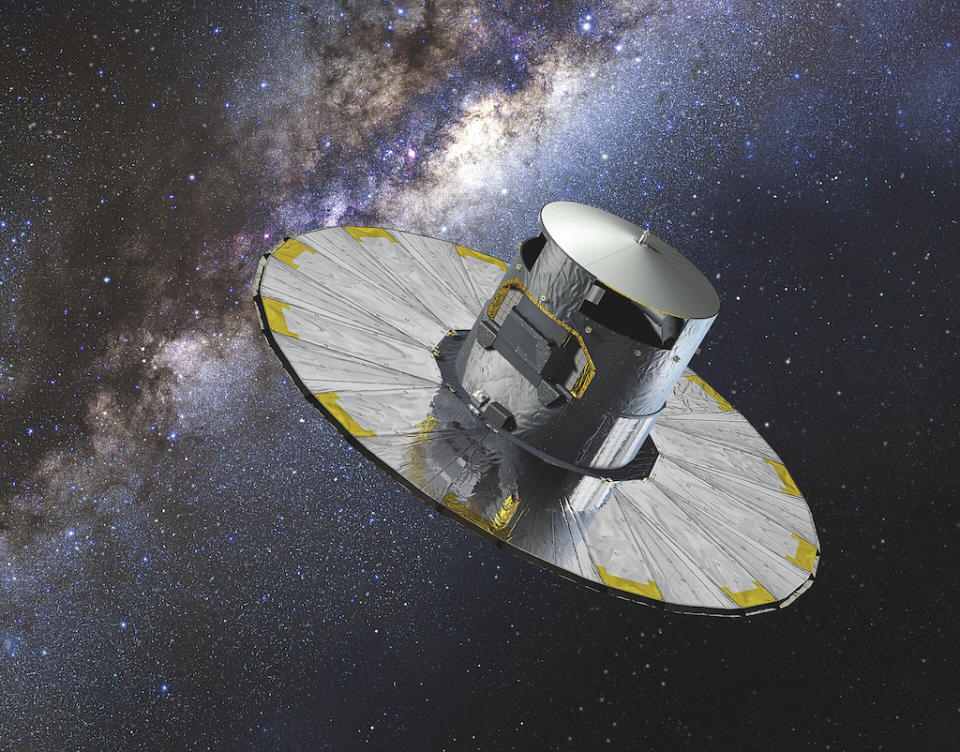

He credits the return of the binary star to decades of cosmic data collected by the European Space Agency’s star-mapping space telescope, Gaia.

Gaia launched in 2013 on a mission to create detailed measurements of a billion stars throughout the Milky Way galaxy and beyond. By mapping the movements, luminosities, temperatures and compositions of these stars, Gaia aims to create the most accurate three-dimensional model of our cosmic backyard ever.

The most recent data drop from Gaia was on October 10, 2023, and contained data on 1.8 billion stars. Amazingly, this was just a taste of what’s to come with the fourth major data drop from the space telescope, known as Gaia Data Release 4 (DR4). Gaia is powered by a technique called “Astrometry,” almost adapted to the investigation of stars with companions.

“Astrometry measures distances to stars and detects their ‘wobble’ on the sky due to binary companions,” said El-Badry. “The sheer size of Gaia’s data sets means that many things are included that have never been seen before: Gaia has already given us orbital solutions for about 50 times more binaries than all previous missions.”

When two come

Despite our familiarity with (and implicit bias towards) single-star systems, thanks to the fact that we orbit such a lonely interstellar body, binaries are more common in the Milky Way than imagined . About 50% of stars around the size of the Sun have a binary partner, and this proportion increases to about 75% for more massive stars.

“More than half of all stars are binaries!” Said El-Badry. “So if you want to understand the evolution of ‘typical’ stars, you need to account for the presence of their counterparts.”

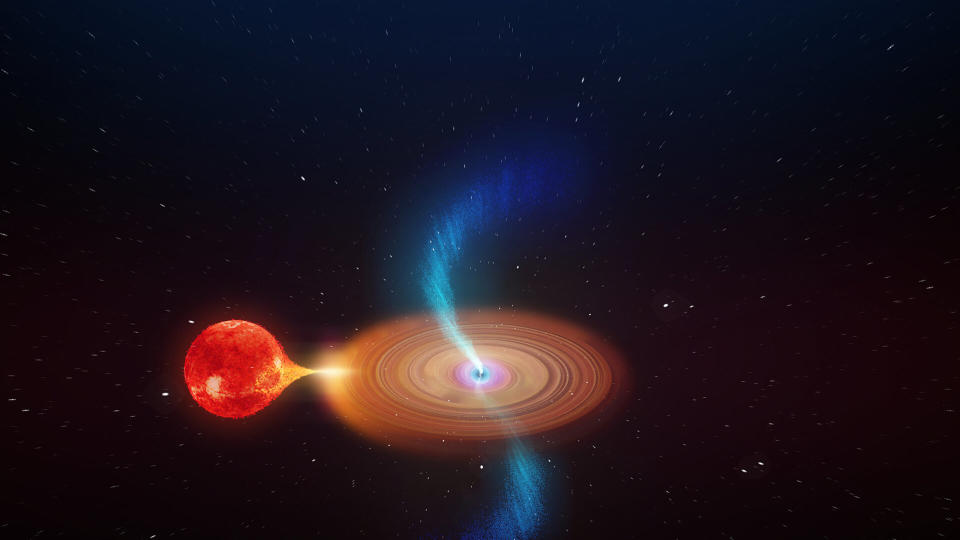

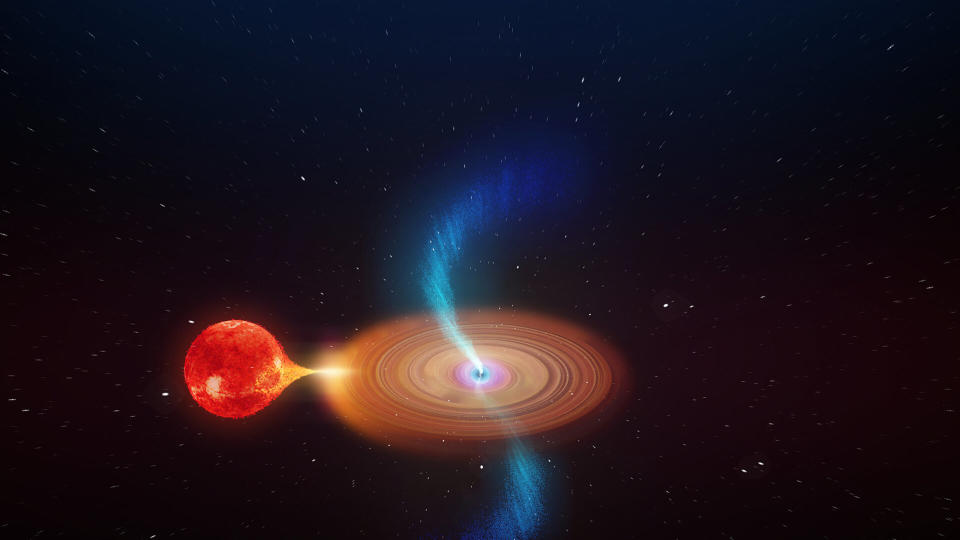

These binary systems allow scientists to study unseen phenomena around individual stars, such as the sun. This includes what happens during mass transfer from a star to its binary partner, events that result in one star being kicked out of a binary system. The systems can also help us understand what happens when stars collide and merge into one.

Gaia data can generally show the kinds of distances that binary stars orbit each other even when those distances are very wide, giving a better picture over a wider range of binary separations than other missions.

“Alternative binaries give us the ability to measure star masses directly through the stars’ gravitational effects on each other, which we can’t do otherwise,” El-Badry explained. “This showed that there is an excess population of binaries in which the two stars are almost exactly the same mass, even when separated by hundreds and thousands of times the distance between the Earth and the sun.”

Gaia didn’t just influence the number of stellar binaries she physically exposed, however. The ESA spacecraft also gave us better estimates of the distance of binary stars as a whole, which El-Badry said had previously been a “major roadblock” in astrophysics.

The Gaia data can also tell us something about binary systems where a star is orbited by something more exotic, such as a white dwarf, neutron star, or black hole. These systems emit gravitational waves as their components spiral around each other.

“Binaries also allow the detection of dark objects such as black holes, which we could not see otherwise, through their gravitational effects on luminous companions,” El-Badry said, adding that this could help astronomers better understand better find out how common a black hole companion is to ordinary stars. and how these extremely exotic systems could form.

This renaissance in binary star studies comes at the right time, coinciding with renewed interest in understanding how these systems formed – one fueled by recently detected gravitational waves from black holes and star binaries neutrons.

RELATED STORIES:

— A new collection of Gaia data will reveal the dark history and future of the Milky Way

— The alien planet of the newly raptured is undergoing nuclear fusion

— Gaia spacecraft look at star mapping of a pair of Jupiter-like planets

The future looks bright for binary stars, and El-Badry is genuinely optimistic that the trends of the 90s may one day make a similar revival.

“Hopefully phones will be flipped, they won’t have to write so many emails, and all the Spice Girls will come back,” said the CfA researcher. “I’m less keen to see low-rise jeans and curly hair equate to ‘being ugly’ in every teenage movie back then.”

El-Badry’s review of a decade of Gaia binary star data is published on the arXiv paper repository site.