One of the major contributors to record global temperatures over the past year – El Niño – is almost gone, and its opposite, La Niña, is on the way.

Whether that’s a relief or not depends in part on where you live. Above-normal temperatures are still predicted across the US in the summer of 2024. And if you live along the Atlantic or Gulf coasts of the US, La Niña can add to the worst possible mix of climate conditions to trigger a hurricane.

Pedro DiNezio, an atmospheric and oceanic scientist at the University of Colorado who studies El Niño and La Niña, explains why and what lies ahead.

What is La Niña?

La Niña and El Niño are two recurring climate patterns that can affect the weather around the world.

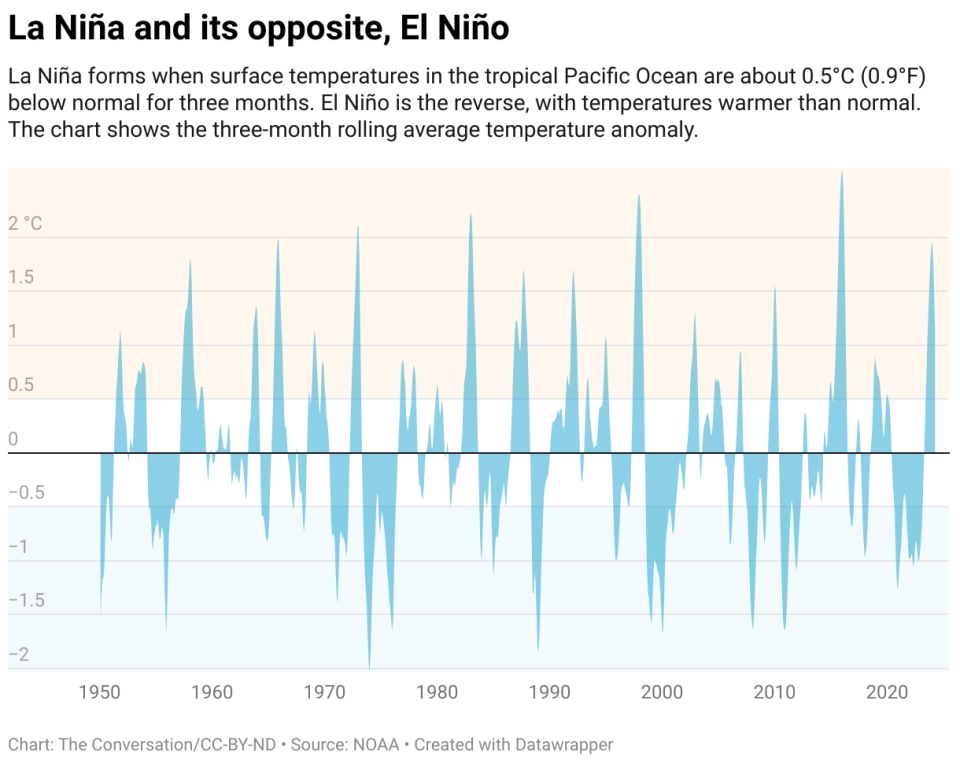

Forecasters know that La Niña has arrived when temperatures in the eastern Pacific Ocean along the equator west of South America cool by at least half a degree Celsius (0.9 Fahrenheit) below normal. During El Niño, the same region warms instead.

Those temperature fluctuations may seem small, but they can affect the atmosphere in ways that run across the planet.

The tropics have an atmospheric circulation pattern known as the Walker Circulation, named after Sir Gilbert Walker, an English physicist in the early 20th century. Walker Cruises are basically huge loops of air rising and falling in different parts of the tropics.

Normally, air rises over the Amazon and Indonesia as moisture from the tropical forests makes the air more buoyant, and descends over East Africa and the eastern Pacific Ocean. During La Niña, those loops strengthen, creating stormier conditions when they rise and drier conditions where they descend. During El Niño, ocean heat in the eastern Pacific shifts those loops instead, so the eastern Pacific becomes stormier.

El Niño and La Niña also affect the jet stream, a strong current of air that blows from west to east across the US and other mid-latitude regions.

During El Niño, the jet stream tends to push storms toward the subtropics, making these dry areas wetter. Conversely, mid-latitude regions that would normally experience storms become drier as storms move.

This year, forecasters are expecting a quick transition to La Niña – probably by late summer. After a strong El Niño, as the world saw in late 2023 and early 2024, conditions tend to transition fairly quickly to La Niña. How long it will stick is an open question. This cycle usually changes from extreme to extreme every three to seven years on average, but while El Niños tend to be short-lived, La Niñas can last two years or longer.

How does La Niña affect hurricanes?

Temperatures in the tropical Pacific Ocean control wind shear over large parts of the Atlantic Ocean.

Wind shear is a difference in wind speeds at a different height or direction. Hurricanes have a harder time maintaining their column structure during strong wind shear because stronger higher winds push the column apart.

La Niña produces less wind shear, which puts the brakes on hurricanes. That’s not good news for people who live in hurricane-prone regions like Florida. In 2020, during the last La Niña, there were 30 tropical storms and 14 hurricanes in the Atlantic, and 21 tropical storms and seven hurricanes in 2021.

Forecasters are already warning that this year’s Atlantic storm season could rival 2021, due in large part to La Niña. The tropical Atlantic is also extremely warm, with sea surface temperatures on record for more than a year. That heat affects the atmosphere, causing more atmospheric movement over the Atlantic, fueling hurricanes.

Does La Niña mean drought returns to the US Southwest?

The US Southwest’s water supplies are likely to be OK for the first year of La Niña because of all the rain this past winter. But there are often problems in the second year. A third year could lead to severe water shortages, as the region saw in 2022.

Drier conditions also lead to more extreme fire seasons in the West, especially in the fall, when winds pick up.

What happens in the Southern Hemisphere during La Niña?

El Niño and La Niña influences are almost a mirror image in the Southern Hemisphere.

Chile and Argentina tend to experience drought during La Niña, while the same phase results in more rain in the Amazon. There were major floods in Australia during the last La Niña. The Indian monsoon is also favored by La Niña, which means above-average rainfall. The effects are not immediate, however. In South Asia, for example, the changes tend to occur a few months after La Niña officially appears.

La Niña is particularly bad for eastern Africa, where vulnerable communities are already in long-term drought.

Is climate change influencing the impact of La Niña?

El Niño and La Niña are now occurring on top of the effects of global warming. That can make temperatures worse, as the world saw in 2023, and precipitation can go off the charts.

Since the summer of 2023, the world has had 10 straight months of record global temperatures. Much of that heat is coming from the oceans, which are still at record temperatures.

La Niña should cool things down a bit, but greenhouse gas emissions that drive global warming are still rising in the background. So, while fluctuations between El Niño and La Niña can cause short-term temperature swings, the overall trend is towards a warming world.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world.

It was written by: Pedro DiNezio, University of Colorado Boulder.

Read more:

Pedro DiNezio receives funding from the NSF.