Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on exciting discoveries, scientific advances and more.

“Do you think every fingerprint is really unique?”

It’s a question a professor asked Gabe Guo during a casual conversation while stuck at home during the Covid-19 lockdown, waiting to start his freshman year at Columbia University. “Little did I know that conversation would set the stage for the focus of my life for the next three years,” Guo said.

Guo, now a senior undergraduate in Columbia’s computer science department, led a team that studied the topic, with professor Wenyao Xu of the University of Buffalo as one of his co-authors. Published this week in the journal Science Advances, the paper appears to upend a long-accepted truth about fingerprints: They are not, Guo and his colleagues argue, all unique.

In fact, the work was rejected by journals several times before the team appealed and was eventually accepted by Science Advances. “There was a lot of pushback from the forensic community at first,” recalled Guo, who had no background in forensics before the study.

“For the first iteration or two of our paper, they said it’s a known fact that no two fingerprints are the same. I think that really helped improve our study, because we didn’t keep adding more data to it, (increasing accuracy) until the evidence was incontrovertible in the end,” he said.

A new look at old prints

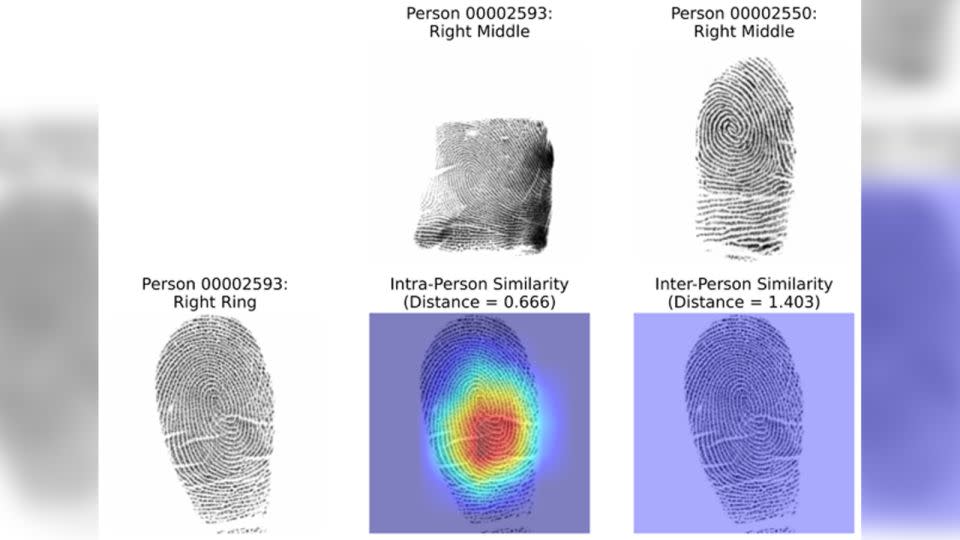

To achieve the surprising results, the team used an artificial intelligence model called a deep contrast network, which is commonly used for tasks such as face recognition. The researchers added their own twist and then fed a US government database of 60,000 fingerprints in pairs that sometimes belonged to the same person (but from different fingers) and sometimes belonged to different people.

As it worked, the AI-based system found strong similarities between fingerprints from different fingers of the same person and was therefore able to tell when the fingerprints belonged to the same person and when they did not yes, to be exact for one pair. a peak of 77% – indicating that each fingerprint is “unique”.

“We found a rigorous explanation for why this is so: the angles and curvatures in the center of the fingerprint,” Guo said.

For hundreds of years of forensic analysis, he said, people have been looking at various features called “minutiae,” the branches and endpoints in fingerprint ridges that are used as traditional markers for fingerprint identification. “They are great for fingerprint matching, but not reliable for finding correlations among fingerprints from the same person,” Guo said. “And that was our insight.”

The authors stated that they are aware of potential biases in the data. While they believe the AI system works largely the same way across gender and race, for the system to be usable in real forensics, more careful validation is needed by analyzing a larger database of fingerprints and wider, according to the study.

However, Guo said he is confident the discovery can improve criminal investigations.:

“The most immediate application is that it could help generate new leads for cold cases, when the fingerprints left at the crime scene come from different fingers than those on file,” he said. “But on the flip side, this will not only help catch more criminals. This will also help innocent people to no longer need to be investigated unnecessarily. And I think that’s a win for society.”

‘Accident in a teacup’?

Using deep learning techniques on fingerprint images is an interesting topic, according to Christophe Champod, professor of forensic science at the School of Criminal Justice at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland. Champod, however, said that he was not involved in the study, that he does not believe that anything new was discovered with the work.

“Their argument that these shapes are somewhat correlated between fingers has been known since the early days of fingerprinting, when it was done by hand, and has been documented for many years,” he said. “I think they have oversold their paper, due to a lack of information, in my opinion. I’m happy they’ve got something recognizable again, but basically, it’s teacup weather.”

In response, Guo said that no one had systematically quantified or used the similarities between fingerprints from different fingers of the same person until the new study.

“We are the first to clearly point out that the similarity is due to the ridge orientation in the middle of the fingerprint,” Guo said. “In addition, we are the first to attempt to match fingerprints from different fingers of the same person, at least with an automated system.”

Simon Cole, a professor in the Department of Criminology, Law and Society at the University of California, Irvine, agreed that the paper is interesting but said its practical utility is overstated. Cole was also not involved in the study.

“We were not ‘wrong’ about fingerprints,” he told forensic experts. “The unproven but implicitly true claim that no two fingerprints are ‘exactly the same’ is not refuted when the fingerprints are found to be similar. It was always known that fingerprints from different people, and from the same person were always similar.”

The paper said the system could be useful in crime scenes where the fingerprints obtained from different fingers than those in the police record, but Cole said this can only happen in rare cases, because when prints are taken, every 10 fingers and often. palms are regularly recorded. “I don’t understand when they think that only part of the person’s fingerprints, but not all, will be on record,” he said.

The team behind the study say they are confident in the results and have open-sourced the AI code for others to check, a decision both Champod and Cole praised. But Guo said the importance of the study goes beyond fingerprints.

“This isn’t just about forensics, it’s about AI. Humans have been looking at fingerprints since we’ve been around, but no one noticed this similarity until our AI analyzed it. That’s just about the power of AI to automatically identify and extract relevant features,” he said.

“I think this study is just the first domino in a huge sequence of these things. We will see people using AI to discover things that were plainly hidden in plain sight, right in front of our eyes, like our fingers.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com