E-commerce may make shopping more convenient, but it has a dark side that most consumers never see.

Say you order yourself an electric toothbrush and two shirts during a sale on Amazon. You unpack your order and discover that the electric toothbrush won’t cut and that only one shirt fits you. So, you decide to return the unwanted shirt and the electric toothbrush.

Returns like this may seem simple, and are often free to the consumer. But those returns can be expensive for retailers to manage, so much so that many returns are thrown out.

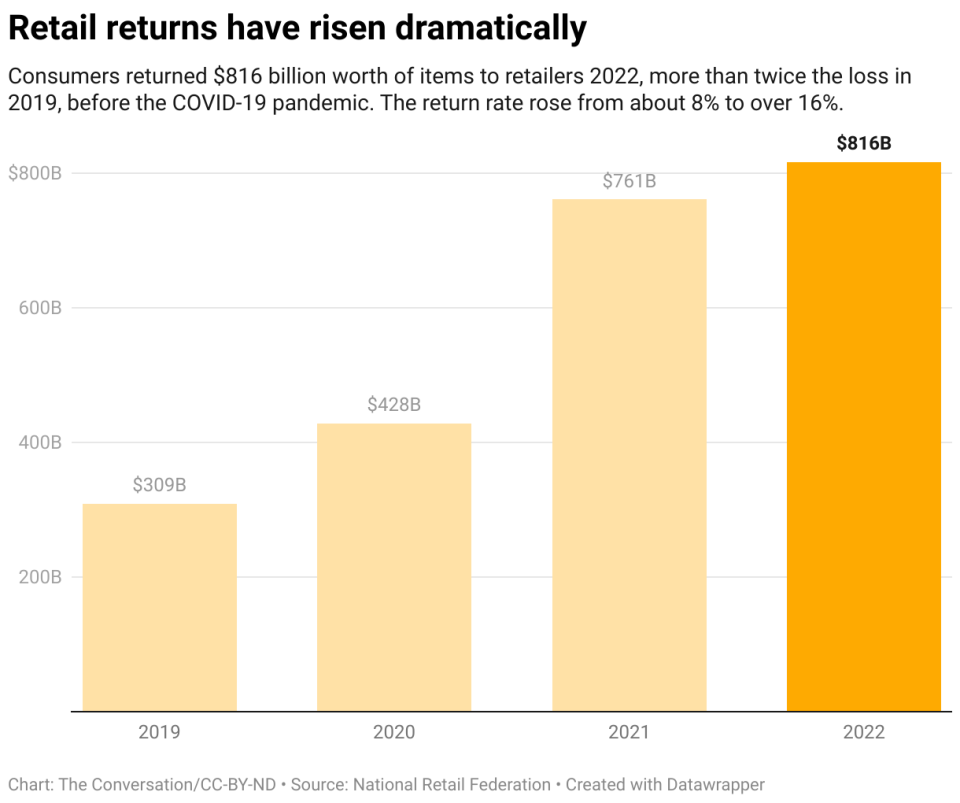

In 2022, returns cost retailers an estimated US6 billion in lost sales. That’s almost as much as the US spent on public schools and almost double the cost of returns in 2020. The wrapping process, with shipping and packaging, also generated about 24 million metric tons of planet-warming carbon dioxide emissions in 2022 .

Together, costs and emissions create a sustainability problem for retailers and the planet.

As a supply chain management researcher, I follow developments in retail logistics. Let’s take a closer look inside the black box of product returns.

Returns start with one thousand transports

So, you repackaged your unwanted shirt and electric toothbrush and drove them to UPS, which has an agreement with Amazon for free returns. Now what?

UPS transports those items to the retailer’s warehouses dedicated to processing returns. This step in the process costs the retailer money – 66% of the cost of an item by one estimate – and releases carbon dioxide as trucks and planes transport goods hundreds of miles. Waste is made of plastic, paper or cardboard from the return package.

It takes two to three times longer to process a return than when the item is originally shipped – it has to be unpacked, inspected, repacked and re-routed. That adds more to the cost to the company, especially in a tight labor market. Workers must manually unpack the items, inspect them and, based on the reason for return, decide what happens next.

Restocking and reselling means more miles

If a warehouse worker determines that the shirt in our example can be resold, the shirt will be repackaged and sent to another warehouse.

When another consumer orders the shirt, it will be ready to be packed and shipped.

In-store returns can significantly reduce warehousing and transportation costs, but it may not be convenient for the consumer to drive to a brick and mortar store. Only about a quarter of online purchases are returned in person to the store.

Refurbishment, if repair costs less than the product

If the item is defective, like the electric toothbrush in our example, the warehouse worker could send it back to the manufacturer for repair and refurbishing. It would be repackaged and loaded onto a truck and possibly a plane to be sent to the manufacturer, resulting in more carbon dioxide emissions.

If the electric toothbrush can be repaired, the refurbished product is ready to be sold on the consumer market again – often at a lower price.

Refurbishing products helps achieve a closed-loop supply chain where products are reused rather than disposed of as waste, making the process more sustainable than buying a new item.

Sometimes, however, repairs cost more than the product can be resold. When it is more expensive to restock or refurbish a product, it may be cheaper for the retailer to dispose of the item.

Landfills are a common destination for returns

If the company cannot economically resell the shirt or refurbish the electric toothbrush, the outlook for these items is bleak. Some are sold in bulk to discount stores. Products that are returned are often sent to landfills, sometimes overseas.

In 2019, approximately 5 billion pounds of waste from returns were sent to landfills, according to an estimate from return technology platform Optoro. By 2022, the waste was estimated to almost double to around 9.5 billion pounds.

The era of free returns might not last

In the past, customers who wanted to return items by mail were often expected to do so on their own dime. That changed after Amazon started offering free returns and providing easy-to-use drop-off locations at UPS or Kohl’s stores. Other retailers followed suit to compete, and many saw free results as a way to keep shoppers coming back.

But that pendulum may be starting to swing back. The percentage of retailers charging for ship returns increased from 33% to 41% in 2022.

Retailers are using various other techniques to lower the rate of return, waste and losses, which ultimately comes back to consumers in the form of higher prices.

Some retailers have shortened the return window, restricted frequent returns or stopped offering free returns. Other strategies include virtual fitting rooms and clearer fitting instructions, which can help reduce clothing returns, and high-quality photos and videos that accurately reflect size and color. If consumers use these tools and pay attention to sizes, they can help reduce the footprint of a growing retail climate.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. Like this article? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

It was written by: Simone Peinkofer, Michigan State University.

Read more:

Simone Peinkofer does not work for, consult with, own shares or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and He has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.