Curtly Ambrose remembers the icy stares of his teammates. On the fourth evening of England’s Test in Trinidad & Tobago in 1994, Ambrose bowled a wild swipe.

“I say, ‘boy, I messed up – I’ve got to get something magical out of the bag’,” recalls Ambrose. “I was very motivated.”

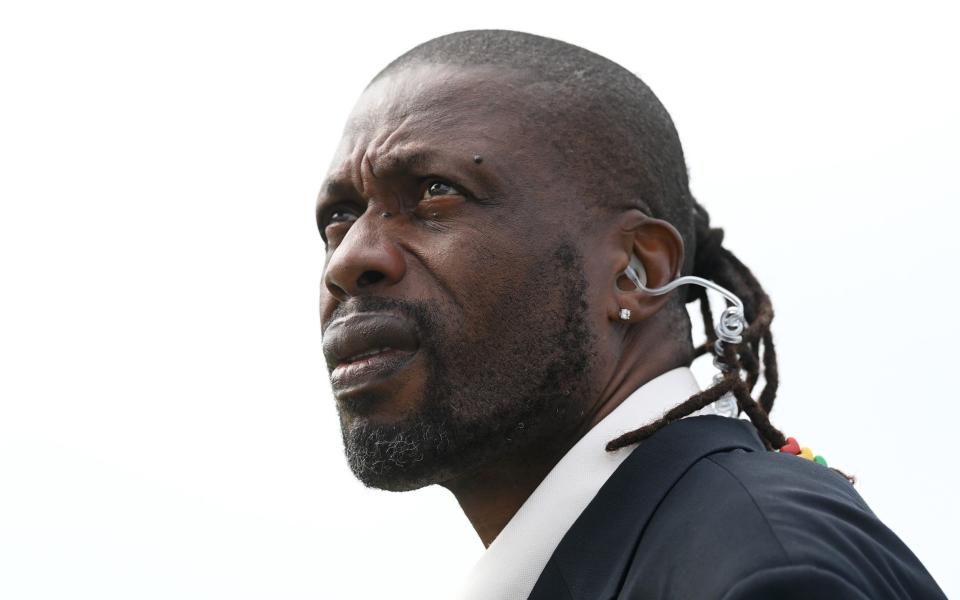

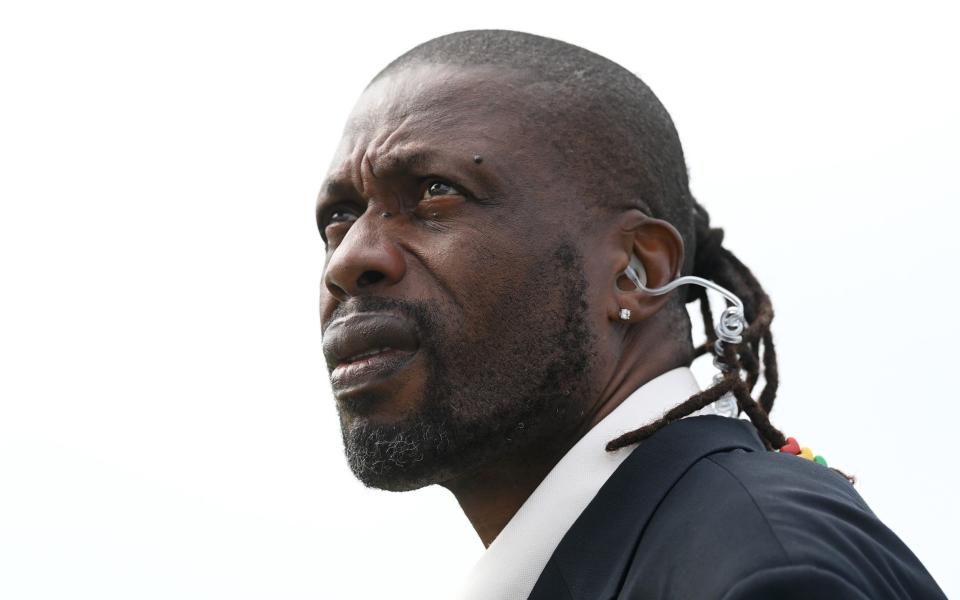

He is now 60 years old, smiling and a smooth talker – unlike his playing career, when he said, ‘Curtly talk to no man’. And yet, with his slender but muscular frame and height of 6ft 8in, it is immediately clear why Ambrose produced some of the most lethal spells in the history of Test cricket.

At the Queen’s Park Oval almost 30 years ago, England began their quest for a 194-run win; 15 goals remained in play on the fourth day. For Ambrose, his personal frustrations, along with the knowledge that he would only have one turn that evening and a game in the balance, were the prelude to a devastating spell of destruction.

“If you want to drive, buy a car,” was Ambrose’s love mantra. But in Trinidad, on a pitch now offering some low bounce, Ambrose moved his length a bit fuller. His first ball reached back to hit Michael Atherton’s front pad in line with the stumps. Ambrose’s arms were now spinning around in anticipation. When Steve Bucknor raised his finger, Ambrose whirled his arms, and trademark white wristbands, in jubilation.

“When you get a wicket, suddenly you can bowl a yard or two faster, because it gives you a lot of energy. So I was really pumped up. And it fell into place perfectly.”

He made an exciting cocktail: a towering bowler who found speeds of 90mph while taking advantage of some uneven bounce, which was applauded by the large Queen’s Park crowd. For all the ignominy of being bowled out for 46 – still England’s lowest Test total since 1877 – the score owed to Ambrose’s extraordinary bowling far outweighed England’s inconsistency.

When Mark Ramprakash was run out later in the opener, England were in for a shock. “That opened the floodgates,” recalls Ambrose. “England was in a bit of a panic.

“When I’m in a certain kind of zone, I’ve always felt invisible. That’s how I feel at that moment. I could do no wrong. And I don’t think any batter on the planet can beat me when I have that kind of attitude.”

In barely an hour, Ambrose smashed the stumps of Robin Smith, Alec Stewart and Graham Thorpe. He walked out with six wickets in 7.5 overs; England were 40-8, and were bowled out for 46 the next morning.

A year earlier, Ambrose had an even more devastating spell: 7-1 off 32 balls at Perth. Once again, frustration was the catalyst: this time, Ambrose believed he had wasted the new ball on the first morning at the WACA, where the series was poised at 1-1 in the decisive Test.

“My first gig was really a joke,” he says. “I was bowling a bit too short. I was bowling my regular length and on that surface the batsmen were going away.”

At lunch, with Australia 59-2, Ambrose ate nothing. “I sat there and said to myself, ‘you’ve messed up’.”

As the West Indies returned to the field, captain Richie Richardson asked Ambrose how he was feeling. “I said ready to go. And I made the adjustment, bowling a bit fuller – not a half-volley length, but a length that the batsmen looked like they could drive.”

The difference, he reckoned, was about a metre: enough to force batsmen camped on the back foot to go forward instead. “The keeper gave in a lot and he slips trying to drive because I changed my distance.

“That’s what fast bowling is all about – the surface you’re playing on and making adjustments accordingly. And I did that and it worked perfectly.

“Seven wickets for one run in an innings – that’s unheard of. That thing happened once in a lifetime, if ever, and against Australia, man!”

‘They looked too cocky for my liking’

These two great spells showed how Ambrose could do his best if he got out of it, whether it was personal frustration or the opposition.

“I’m at my most dangerous when I’m upset or when my back is against the wall. Something will upset me. And then I get upset. And then I also felt that I could bowl maybe a few yards faster.

“Maybe a bat will just walk around and look a little too tough for my liking. I will say – you know what, I’m going to take care of you. It could be anything to inspire me.”

Perhaps no batsman felt this Ambrose tendency more than Steve Waugh. The two shared fierce battles throughout the 1990s, as Australia claimed the West Indies crown at the top of the Test game. In Trinidad in 1995, teammate Kenny Benjamin told Ambrose at lunch that Waugh swore at him.

Now Ambrose abandoned his usual maxim – “I find that the five and a half ounces will do me enough. I don’t say anything.

“When we came back from the break, we went back to it again. And someone said to me ‘ask him if he said it’. And I said to him, ‘did you say so and so to me?’ He didn’t say yes, he didn’t say no. He simply said ‘I can say whatever I want’. That was for me.”

This was Test cricket at its most primal. Ambrose’s anger caused him to confront Waugh, and Richardson had to pull him away.

“I wanted to hit him physically because I demanded more respect from him.” Characteristically, Ambrose showed his anger when he took nine wickets for 65 runs in the West Indies win. “We haven’t talked about it.”

‘I’m a freak of nature’

Ambrose never aspired to be a Test player. As a boy, his great love was basketball.

It was said that John F Kennedy became president because his older brother was unable to fulfill the family dream. Ambrose, too, fulfilled the hopes originally invested in another. His cricket-loving mother, who used to listen to Test matches on her transistor radio in Swetes, her village in Antigua, dreamed of her eldest son becoming a Test cricketer.

“My older brother used to play club cricket,” recalls Ambrose. “When he emigrated to the United States to join my father I was naturally next in line.”

In his late teens, Ambrose blossomed so quickly that some schoolboys didn’t recognize him when they saw him bowl on TV. At the age of 20, Ambrose started playing club cricket for Swetes. Within four years, after just six first-class matches, he was playing for the West Indies.

And so Ambrose didn’t need the 10,000 hours of training said to be necessary to achieve greatness – a theory that has largely been debunked anyway.

“It was natural for me,” he says. “According to Desmond Haynes, I’m a freak of nature.”

At first Ambrose relied on the classic fast bowler’s combination: following a bouncer with a yorker. In Test cricket, he quickly learned, this was not enough.

“I’ve developed that short delivery where batters aren’t sure whether to come forward or go back – an ‘in-between’ length. He could not leave the guys at all. They had to watch play.

“I was never a swing bowler. I was relying on hitting the pitch and getting the ball away from them or going back or going straight forward.”

Some great fast bowlers accept being driven for boundaries as an unavoidable cost of doing business. For Ambrose every run scored against him was more like a personal affliction. No one who took more than his 405 Test wickets, not even Glenn McGrath, was so frugal.

“I’m a very proud man. Everything I do, I want to be the best.

“I hate giving runs. I have to work hard to take wickets so I won’t be easy for you as a batsman.” As a generation of Test batsmen could attest, Ambrose never did.