One of the strongest measures of the Earth’s changing climate is that winter is warming faster than other seasons. The cascade of changes that come with it, including ice storms and rain in regions that were once reliably frozen, are symptoms of what I call “winter warming syndrome”.

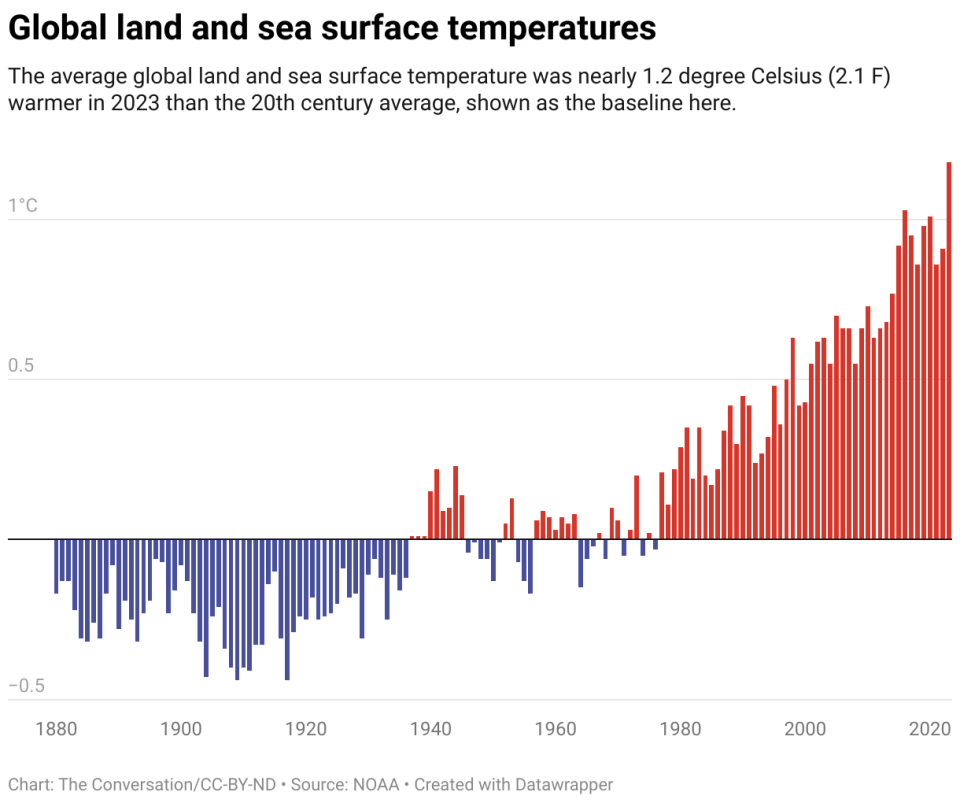

Winter warming reflects the global accumulation of heat. During the winter, direct heat from the Sun is weak, but storms and shifts in the jet stream bring warm air up from warmer latitudes into the northern US and Canada. As the earth’s temperature and oceans warm, that stored heat affects both temperature and precipitation.

Warming is evident in changes to growing seasons, reflected in recent updates to planting hardiness zones printed on the back of seed packets. These maps show the northward and, sometimes, westward movement of freezing temperatures in eastern North America.

The transition of this freezing line between snow and rain can mean ice storms in places and times that communities are not ready to handle, as many parts of the US saw in early 2024.

Ice storms and wet snow

I study the impact of global warming and have recorded climate and weather changes over the years.

On average, freezing temperatures are moving north and, along the Atlantic coast, towards the interior of the continent. For individual storms, the transition to freezing temperatures even in the dead of winter can be as far north as Lake Superior and southern Canada in places where, 50 years ago, it was reliably below freezing from early December to February.

When the temperature is close to freezing, water can be rain, snow or ice. An increase in ice storms is seen in regions on the colder side, which would historically be below freezing and snow.

The character of snow also changes near the freezing line. When the temperature is well below freezing, the snow is dry and fluffy. Near freezing, the snow has large, heavy, wet flakes that turn roads into slush and cling to tree branches and bring down power lines.

Because the climate where blizzards are forming is warmer due to a global accumulation of heat, and wetter due to increased evaporation and warmer air that can hold more moisture, individual blizzards can produce snowfall tougher too. However, as temperatures get warmer in the future, the scales will tip towards rain, and the total amount of snow will decrease.

In fact, on the warmer side of the freezing line, winter rain is already becoming the dominant form of precipitation, a trend that is expected to continue. With the warmer oceans as the main source of moisture, the already wet Eastern US can expect more winter precipitation over the next 30 years. Looking to the future, wet soggy winters are more likely.

Disaster and water planning becomes more difficult

For communities, planning for water supplies and extreme weather becomes more complex in a rapidly changing climate. Planners cannot count on the weather 30 years in the future to be the same as the weather today. It’s changing too fast.

In many places, snow will not continue until late spring. In regions like California and the Rockies that depend on the snowpack for water throughout the year, those supplies will be less reliable.

The rain that falls on the snowpack can also speed up melting, trigger flooding and alter the flows of trees and rivers. This indicates changing runoff patterns in the Great Lakes, and caused flooding on the East Coast in January 2024.

For road planners, the rate of freeze-thaw cycles that could damage roads during winter will increase in many regions that are not used to such rapid transitions.

A particularly interesting effect occurs in the Great Lakes. Already, the Great Lakes don’t freeze as quickly or as completely as they used to. This has major effects on the famous lake-effect precipitation zones.

Because the lakes are not frozen, more water evaporates into the atmosphere. In places where winter air temperatures are still below freezing, snowpack affecting lakes is increasing. The Buffalo, New York region saw 6 feet of snow from one lake-effect storm in 2022. As air temperatures approach freezing, the events are more likely to be rain and ice. this is how it snows.

These changes do not mean that the cold is truly gone. There will be occasions when Arctic air descends into the U.S. This may cause flash freezes and fog as warm wet air rises back over the frozen surface.

Huge consequences for economies

What we have in store for winter warming syndrome is a consistent and strong set of signs of a feverish planet.

November and December will be milder; February and Marches will be more like spring. Winter weather will be more concentrated around January. There will be an unusual variety of snow, ice and rain. Some people might say that these changes are great; there is less snow to shovel and heating bills are down.

But on the other hand, entire economies are set up for winter, many crops depend on cool winter temperatures, and many farmers rely on freezing weather to control pests. Anytime there are changes in temperature and water, the conditions in which plants and animals thrive are altered.

These changes, which affect outdoor sports and recreation, commercial fisheries and agriculture, have huge consequences not only for the ecosystems but also for our relationship with them. In some cases, traditions will be lost, such as ice fishing. All in all, people almost everywhere will have to adapt.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world.

It was written by: Richard B. (Ricky) Rood, University of Michigan.

Read more:

Richard B. (Ricky) Rood receives funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).