I The Secret Agent by Joseph Conrad, a cornerstone of British espionage in a pornographic shop. This hidden horror is somewhere unknown, but on Irving Street, just off Leicester Square.

This hidden history – one that reveals the secrets of the socialists in Soho and the Bolsheviks in Belgravia – is revealed on the Secret Agent Conrad walk, one of the Footprints of London literary walking tours. Other themed walks include Italianate Clerkenwell and Peter Ackroyd’s East End, but I’m here to discover London in the early 20th century, and the real places that inspired Conrad’s most mysterious novel.

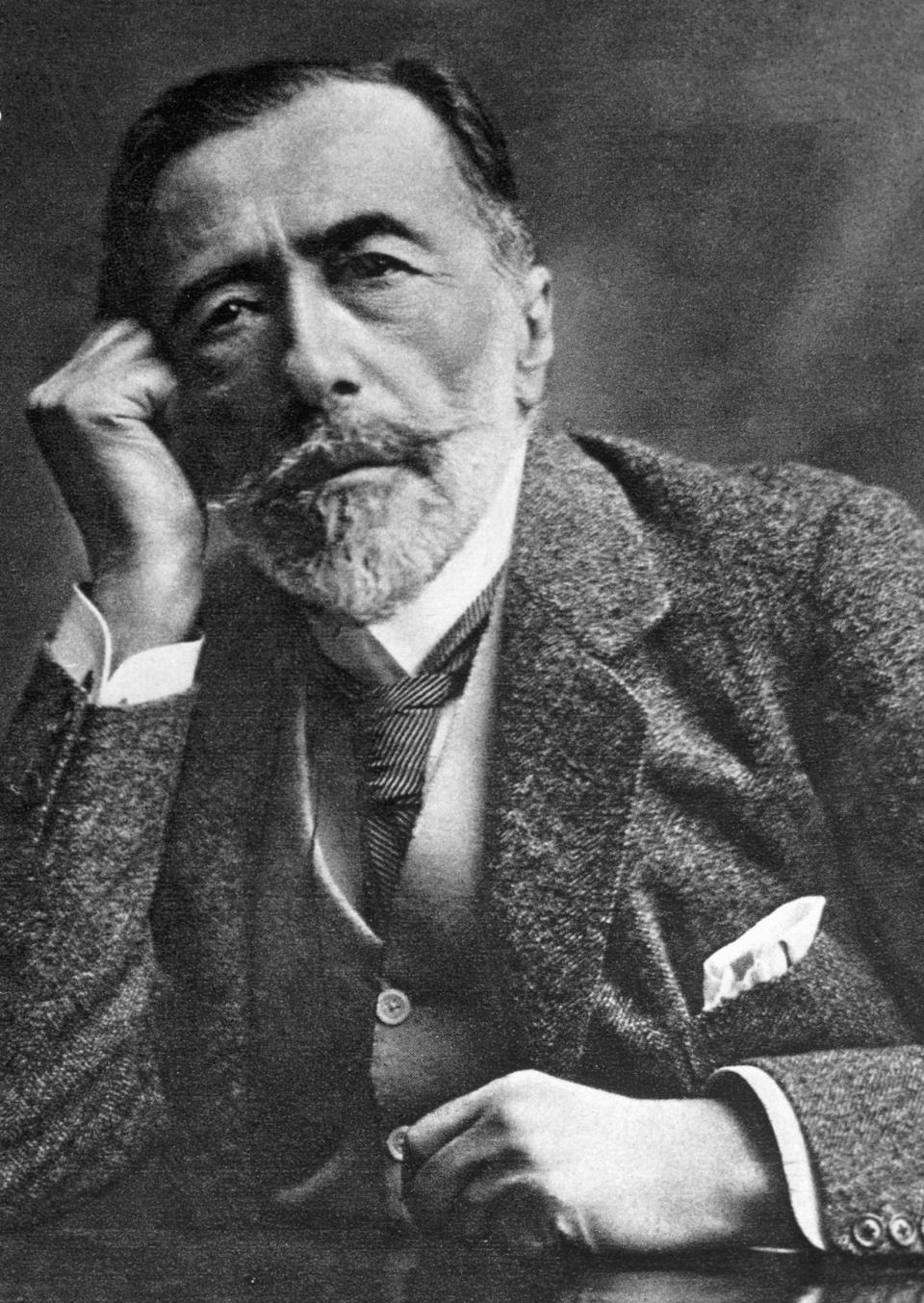

The Secret Agent set in 1886, it follows Adolf Verloc, a spy trying to infiltrate a mysterious, presumably Russian, embassy. He informs a group of anarchists at the behest of the Embassy, and forces his intellectually disabled brother-in-law to bomb the observatory at Greenwich. The political landscape of the book feels quite relevant, but the events are based on the real Greenwich bombing in 1894, in which Frenchman Martial Bourdin was killed when his explosives detonated prematurely. His motives have never been discovered.

I’m guided by Oonagh, a retired archivist who has been leading walks around London for about a decade. We are not following scenes from the novel in chronological order, per sebut following the path of the communards, refugees and political exiles who inspired the author to write.

Conrad was the son of two exiled Polish revolutionaries, which is now somewhat unfashionable. Both died before he was 12; his early life was marked by political turmoil and ill health, spending time in boarding houses for those orphaned by political activity. After a career in the French merchant navy, Conrad eventually moved to Pimlico to write.

Oonagh mischievously suggests that this troubled youth is why the writer is so ambivalent towards his revolutionary characters. He may have hesitated, but Conrad nevertheless knew the communist character of London in the early 20th century.

Take, for example, its many revolutionary meeting places. This is the first stop on the walking tour: on a side street near Tottenham Court Road, we find the one-time meeting house for European exiles. Rudolf Rocker, the German anarcho-syndicalist, spent time here before organizing a strike that influenced Jewish garment workers in the East End in 1912. Now, Stephen Mews has a pub and not much else; its radical history unmarked.

More enigmatic, however, is the cobbled Newman’s Passage, which is accessed via an old smelly path. Once a soup kitchen, the building sheltered French communists, who fled to the British capital when the Paris Commune fell in 1871. Persecuted at home, the radicals gathered across the Channel. The “inflow” of French exiles (actually only about 3,500 arrived in London) was a matter of great concern. The Secret Agent – characters in the book worry that international conspirators are infiltrating the city. Raphoe Street is worth a visit, not for its remarkable beauty but for the ease with which one can imagine its former purpose.

As we walk through Soho, Oonagh produces laminated cards to tell the story of Louise Michel, a French writer and teacher who founded an anarchist school in London, which was closed when explosives were found in the basement. It turned out that Auguste Coulon, promoter of the Special Branch, sent them; Incidentally, Conrad used Coulon as the basis for Chief Heat Inspector i The Secret Agent. Michel is still obscure in Britain, but when she died in 1905, around 100,000 people went to her funeral in Paris. It is a curiously unknown biography, one not helped by Conrad, who has little interest in revolutionary women.

It is remarkable, however, how signs of the city of men remain. We turn a corner on Windmill Street, where an unlicensed Moroccan cafe is part of a terrace of shops. Here, Oonagh tells me, was the Autonomie Club, a social hub for anarchists at the end of the 19th century. Now, a few tables are occupied but it is relatively quiet; you wouldn’t imagine this as a place of revolution. The radicalism was short-lived – it was raided after a membership card was found in Bourdin’s possession, leading to its disbandment.

The journey is not all about intrigue. The Sondheim Theatre, on the corner of Shaftesbury Avenue and Wardour Street, is thought to be the site close to St Martin’s Hall. The hall hosted the first meeting of the International Working Men’s Association, where delegations from across Europe met to discuss the future of the trade union movement. A certain Karl Marx from Germany was present, although he refused to speak. Marx would eventually live, in poverty, nearby, writing and working alongside a fellow communist in Soho. His flat in Dean Street is now marked with a blue plaque.

Lenin was also a local. “He wasn’t that interested in mixing with other people, though,” says Oonagh. Despite his anti-social tendencies, the Russian moved around central London, living in Clerkenwell and spending time at the British Library. It is from here that he invented his revolutionary newspaper, The Sparkwhose aim was to incite rebellion against the tsar.

As a final stop, we head through the bustling streets to Maison Bertaux, a French café. Iced buns, croissants and pastries line the windows, coquettishly hidden behind striped Breton blinds. It was founded in 1871 by a former communist to serve the growing French population, offering pastries and cakes familiar in Paris but completely foreign to London. It’s always popular, with a constant stream of customers rushing through the door for an espresso.

The cafe became popular almost immediately, among refugees and locals alike, and, remarkably, it still is. The city of Conrad is here, it seems, still – if you know where to look.

Footprints of London runs walking tours throughout the year, with tickets starting at £15. Find out more via website. Oonagh Gay, and her fellow guide Sue McCarthy, can also be booked privately through Capital Walks in London – see the website or email oonagh.gay@icloud.com for more details.