A few years after their then chief executive Garry Cook said Manchester City were on the way to becoming “the biggest and best club in the world”, the scoreline suggested he had a point. It was September 2012, a year after Cook’s retirement, and City’s second Champions League campaign got off to a flying start. With five minutes remaining in their opening game, Aleksandar Kolarov scored with a free kick to put them 2-1 up. Against Real Madrid. At the Bernabeu.

Then came the comeback, Karim Benzema and Cristiano Ronaldo scoring. This was not the last injury time goal that City conceded at the Bernabeu but it was an indication of Real’s ability to go back for the established order. City did not win a game in that Champions League campaign, topping their group. Real got their semi-final; even if their standards were barely met.

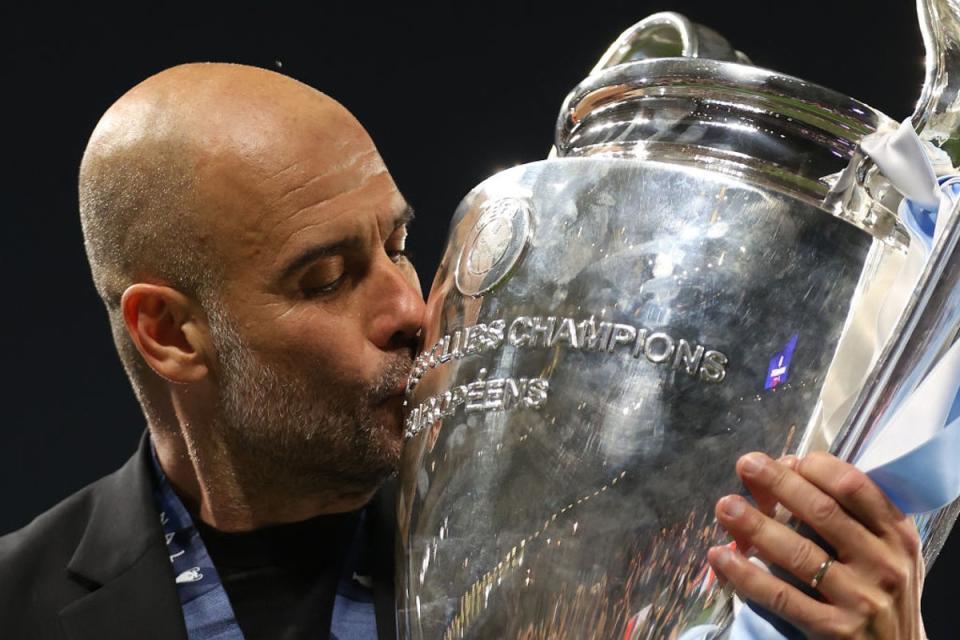

Returning to the Spanish capital for a sixth visit in a dozen years, City already have eight wins in this season’s competition, 10 in a row since they drew at the Bernabeu last year. For all of Cook’s bravado and City silverware, many would still anoint Real as the world’s greatest club. But City’s treble last year gave them a claim to be the best team. But for the fact that they were drawn against each other, they would probably be the two favorites now; even before that, each felt the side most likely to stop the other.

If old and new money have taken different journeys to a similar destination, Real have never been more of a nemesis and antithesis than a role model for City.

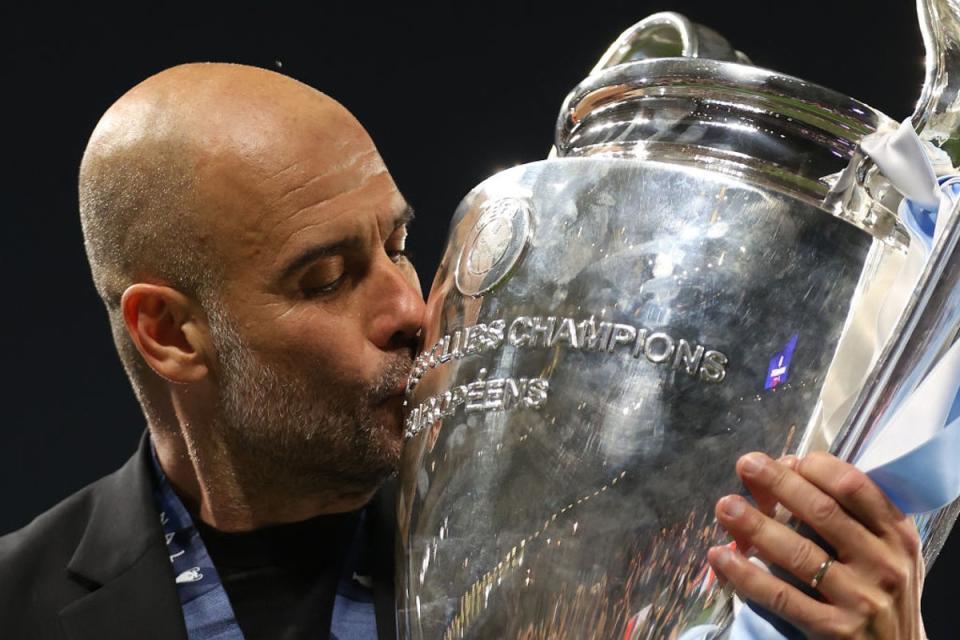

Pep Guardiola grew up in a club that defined itself against Real: they had won six European Cups before he was born, he was a ball boy when Barcelona reached the first final of his life, a midfielder when they came to slow as the champions of the continent. He said they were the “kings of the tournament” when the quarter-final draw was made. For years, he argued that an institution with such a track record had an inherent advantage. Even when City won their inaugural Champions League in Istanbul last year, he said: “We’re only 13 behind them. Be careful, Real Madrid.

Two of Real’s haul of 14 came after City were eliminated; the defining result of the Mancunians’ lone win was a 4-0 hammering of Real at the Etihad Stadium last May. This is a tale of three semi-finals: in the first and under Manuel Pellegrini, whose departure was already confirmed as well as the arrival of Guardiola, City were too slow, settling for a respectable 1-0 loss in Madrid, with only two meeting them. shots on target over 180 minutes.

The 2016 win was Real’s first hat-trick. It showed their ability to prevail in their competition. If both Guardiola and Barcelona have defined an era, the fact is that in the 16 years since his appointment at Camp Nou, the club and the manager have won the Champions League three times, two of them together. Real won it five times. That is their philosophy.

Their most recent victory was in 2022. That ability to find a way to win was most evident against City. Guardiola’s team dominated the semi-final for 178 minutes and lost it. If he followed the theme of City, then specialists in tragicomic ways without winning the Champions League, he also provided the context for last year’s 4-0, which followed a first-leg draw in Spain: the demolition of Real ensured this time, at least, there was no coming back.

City drew at the Bernabeu last season. Their individual victory can then feel obscure: because the return stage took place more than five months later, because of Covid, because it did not facilitate but perhaps the worst European night in the City under Guardiola , the fourth final win for the Lyon side who finished seventh in Ligue Un.

But a decisive 2-1 result in 2020, courtesy of a five-minute turnaround in which Gabriel Jesus and Kevin De Bruyne scored. The loss to Lyon in the next round has been worse since. It may have started City’s rise to elite status in Europe. Since then, they have been finalists, semi-finalists and winners in three subsequent seasons. Their now annual presence in the Champions League can be divided into three phases: the complicated group exits under Roberto Mancini, a six-season period in which they reached the knockout stages but often lost to the best first team they faced, turn there. as a true competitor.

And so they renew their acquaintance with Real as equals and opposites. Barcelona was more of a touchstone for the City; understandable since they took the hierarchy from Nou Camp, in Ferran Soriano and Txiki Begiristain, laying the foundation to get Guardiola. One of the biggest characteristics is that Real has the best English midfielder, in Jude Bellingham, City has the great Spaniard, in Rodri.

Although Robinho was City’s first purchase since the Sheikh Mansour era, a statement signing by Real, they rarely attempted to sign galacticos after Cook’s initial splurge. And City’s financial situation is such that Real cannot raid them for their star; The theory has long been that Sergio Aguero would have happily returned to the Spanish capital but it never came. Now it seems Real are keen on Erling Haaland but that doesn’t mean it will be easy to prize him away from City.

Perhaps, therefore, competition in the 21st century will take place in the transfer market. Now the field is more familiar. Next week’s final will be the 12th meeting in 12 seasons: as many games as City have played against Sunderland in that time, more than against Bolton or Blackburn, Leeds or Nottingham Forest, both Sheffield club together. His fixture list has got a new look.

It could be different. City were initially handed a two-year ban from the Champions League in 2020, 11 days before Jesus and De Bruyne hit the Bernabeu, although it was later overturned. Real were the leaders among the Super League plotters. Instead, they have become an annual Champions League battle, perhaps their dominant duopoly. And as he has for much of his playing and managerial career, Guardiola is taking down Barcelona’s old foes. Be careful, Real Madrid.