In the race to the top of the 19th century, Gustave Eiffel conquered a thousand countries. Or, rather, about 143 meters. The Eiffel tower, at 300 meters, almost doubled the previous “tallest structure” record – held by the Washington Monument since 1884. Before that, the 157 meter Cologne cathedral was a challenge to beat. It was a great moment, France with Mr. Toad out. The country had been under military pressure by the Prussians two decades earlier. Britain was progressing, industrially.

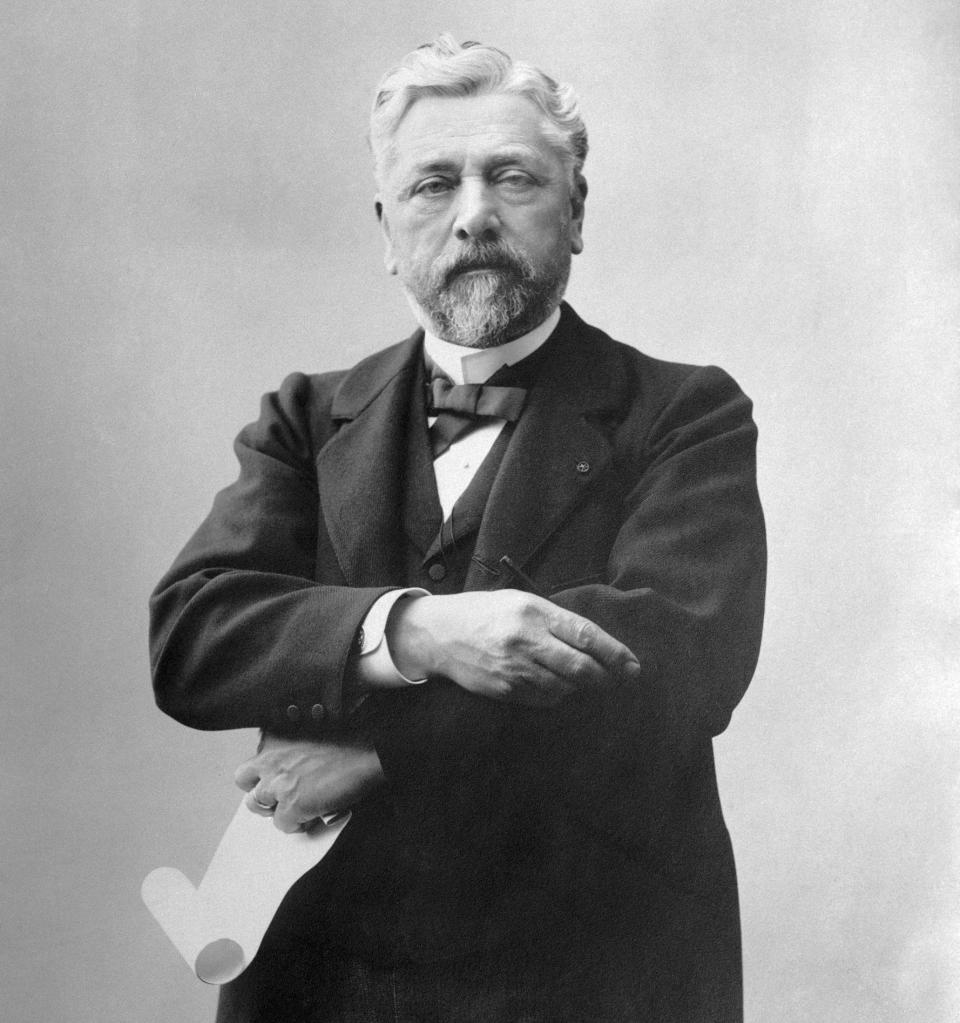

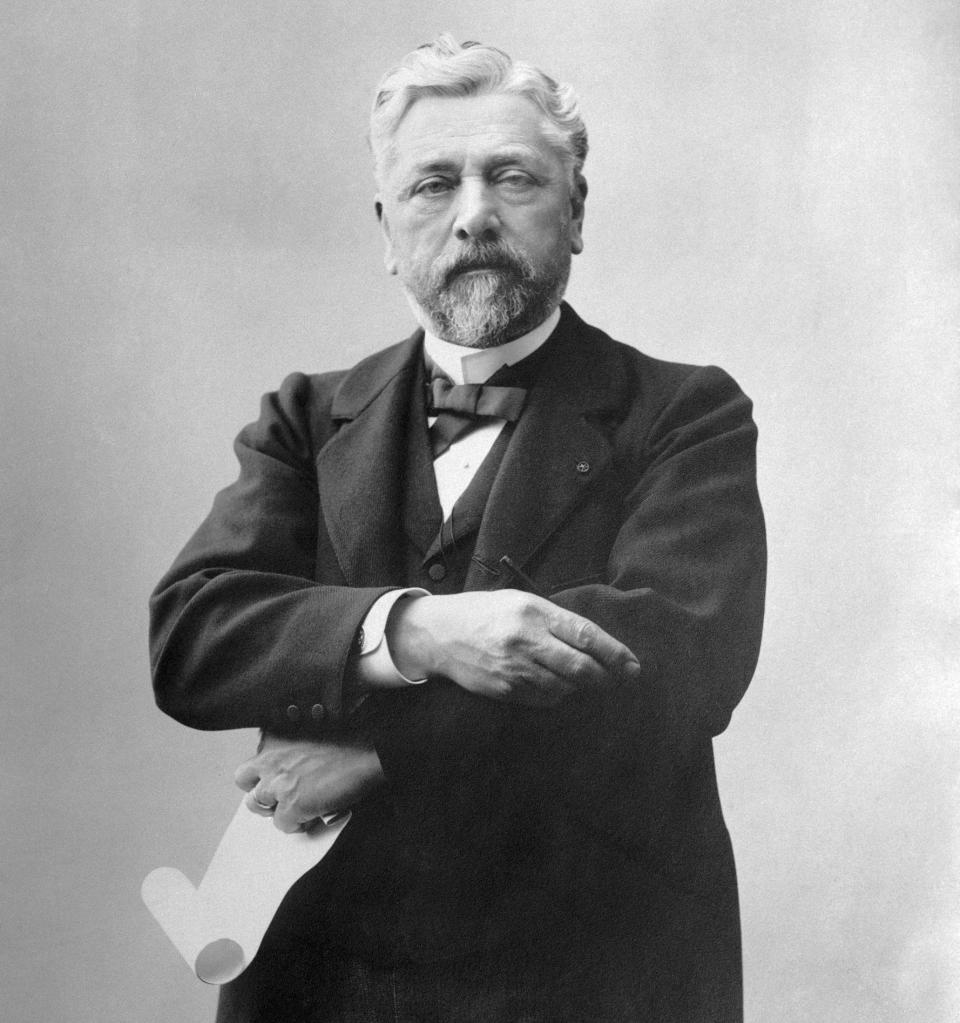

Therefore, the French had to celebrate the centenary of their revolution with a statement of power. Of which was the Paris World’s Fair of 1889. And the world’s largest tower – the world’s largest “building” was central to the impact of the World’s Fair. He was high, he was great, he was useless. “Oh, the happiness! Ohhh… poop, poop!” as Mr. Toad put it. Mr. Eiffel – who, on December 27, will have been dead for a hundred years – was attached to the world.

During the 19th century, height was an obsession in international construction circles (as it still is: see the excitement over the Burj Khalifa, the largest ever – more than two and a half times the Eiffel tower – in Dubai). The target was a thousand feet. A few comrades tried the world’s fair in Philadelphia in 1876. Another planned a large granite column in Paris. They had technical difficulties.

Only Eiffel, the greatest structural engineer of his time, overcame the problems – although he didn’t even build thousands of feet. Not at first, anyway. Three hundred meters comes in at 984 feet. It’s still a great achievement. It was not built for 40 years, when the Chrysler Building in New York went up to 319 meters. (New antennas in the 1950s added 30 meters to the tower, so it overtook the Chrysler.)

In the first place, Eiffel was not particularly interested in the tower project. He already had an international reputation after the success of the Garabit viaduct in the Massif Central and railway bridges in Bordeaux and, in particular, Porto. His engineering business was full of smaller contracts around the world.

But then three of his senior staff came up with workable plans for an iron tower. The boss was lying. He went behind the scenes, using great PR and networking skills to get the job ahead of opponents’ schemes. His offer undoubtedly helped provide 80 percent of the cost.

So, the Eiffel men went ahead, in the teeth of serious opposition – especially, from artists and writers. The tower was to be “a hideous column of bolted metal”, claimed an open letter signed by Charles Gounod, Alexander Dumas and Guy de Maupassant among others. Novelist and art critic Joris-Karl Huysmans described it as “a suppository full of holes”. All this reminds us that ordinary Parisian intellectuals need regular slapping.

Part of Eiffel’s dedication was to pre-assemble the tower’s 18,000 pieces of wrought iron – with millions of heated rivets – at his base in Levallois-Perret, before final assembly, latticework style, on site on the Champ of Mars. There were plenty of other innovative aspects of the construction. However, the low number of deaths was particularly noteworthy. Only one man died among a workforce of 300 on site, most of whom spent their time free-styled along metal beams hundreds of feet above the ground. Photographs show them leaning nonchalantly against props and smoking, obviously unaware of the presence of vertigo.

In just two years, two months and five days, the tower was completed. Gustave Eiffel, who was 57 at the time, climbed the steps in 1710 to the top, carrying the French flag. Despite the disapproval of right-thinking people, he became an instant success. Around two million visitors climbed the stairs or used the hydraulic lifts during the World’s Fair. Eiffel was returning his money.

And then he got into big trouble elsewhere. Eiffel’s involvement in the construction of the Panama Canal went back a long way when the pharaonic project progressed. Hundreds of small investors were wiped out. Eiffel shared the blame. He allegedly invented it. He was vilified throughout France. The courts agreed, condemning him, in the first instance, to two years in prison and a large fine.

It was cleared on appeal. But after the incident Eiffel quit the construction business. Instead he developed his interest in meteorological and aerodynamic research. A wind tunnel he created is still in use in the 16th arrondissement of Paris. He also had to spend time ensuring the future of his tower.

At the beginning, the tower was intended to be temporary, to be dismantled after 20 years. But, by setting up a weather station on top, and then adding radio antennas for the army, Eiffel ensured that it survived. Soon, however, the tower established a parallel pattern of attracting lunatics and conmen. In 1912, the Austrian-born tailor Franz Reichelt threw himself out, wearing a “parachute garment (designed to) preserve lizards from dangerous falls”. It seems that he died before he hit the ground, although it is not clear how they worked out the order.

Later, after the First World War 1, the tower was “sold” to one of France’s most volatile scrap metal merchants, Victor Lustig, once born in Bohemia. The merchant was too embarrassed to make an official complaint, so Lustig was able to try to sell the tower again. This time, he was caught out.

Meanwhile, a replica tower – built in Linndubh in 1894 at 158 meters – was doing the business, not least because of its ballroom and, later, the great Reginald Dixon at the organ. Additional copies were subsequently made. The half-size version, 1999 in Las Vegas, is the most famous. Others include two in China and one each in Paris, Tennessee and Paris, Texas.

Meanwhile, the race for height continued. After the Eiffel tower was dismantled in 1930, the 381 meter 102-storey Empire State Building was topped a year later. It in turn relinquished its title to the first World Trade Center tower in 1970 – and, to show how things have gone on, and up, since then, it’s only 54th tallest in the world now. In the year 2023, there are 43 buildings over 400 meters high in the world.

But none receives more visitors than the six to seven million who climb the Eiffel Tower each year. (The Empire State Building gets four million). It is the Great Tower of the Celts, famous for it. Granted, antennae are up, but they could be disposed of with much less success. In a sense, it is a jolly, vertical quay by the sea, built to do nothing but exist, and please visitors. This is what distinguishes it from almost all other tall buildings, which have a purpose other than being tall.

And it’s really beautiful. On the contrary, the tower is extremely huge – like Albi cathedral or Dwayne Johnson. But he is also light on his feet. Pick up an accordion and he could waltz down the Champ-de-Mars. Take these elements together, and that’s why we like it. That’s why everyone takes a photo – but, of course, the world needs more pictures of the Eiffel tower because it needs more legumes in baskets. The French are painting it gold for the 2024 Olympics. I have a feeling they could have gotten away with such an attractive extravagance. No wonder Mr. Eiffel remains a hero.

How to do it

It costs £25 (per adult over 25) to take the lift to the top. Adding a glass of champagne from the upstairs champagne bar brings that to £44. It is £16 to go to the second floor. Book in advance on toureiffel.paris to avoid queues. The new-ish Madame Brasserie on the first floor is expensive – around £78 for a three-course dinner – but not as expensive as the second-floor Jules Verne, whose five-course tasting menu is from £221. Book in advance at both (restaurants-toureiffel.com).