I remember in college in the late 2000s learning about weather forecasting. My classmates and I would hand draw maps with the current weather systems and then look at the satellite data to paint the picture of what would happen in the coming hours and days.

NOAA weather satellites were good back then, but compared to our orbit now, the difference is night and day. As a broadcast meteorologist, I used the data they provide to provide life-saving information and early warning to billions of people across the United States and even in the Caribbean when threatening weather developed.

And when GOES-U launches on June 25 atop a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket, it will complete NOAA’s GOES-R weather satellite constellation, adding to the capabilities of its siblings and focusing more on space weather.

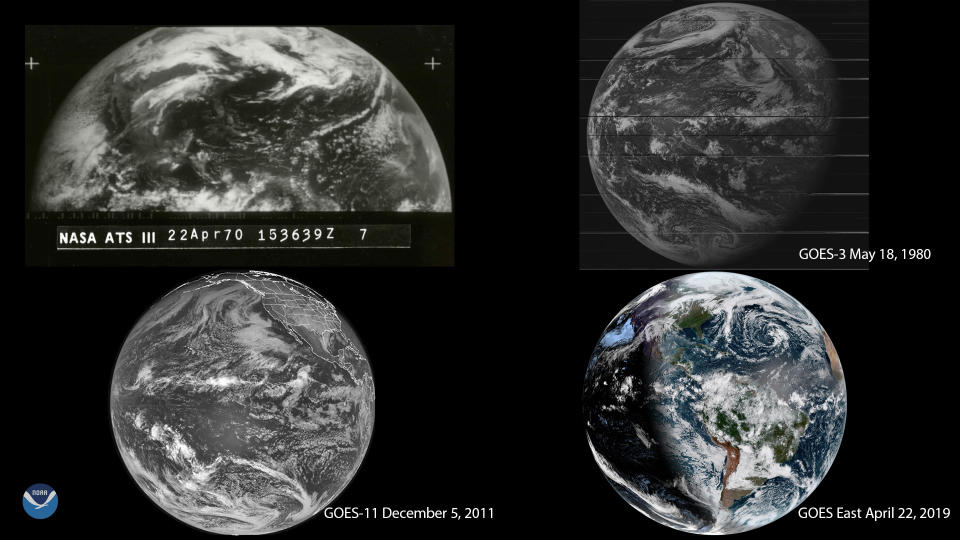

NOAA’s Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES) are nothing new; they have been providing scientists with a steady flow of data and images from space since 1975. But over the years, advances in technology and the lessons learned from each satellite launched up to this point have significantly improved the instruments and the products available with the newer models.

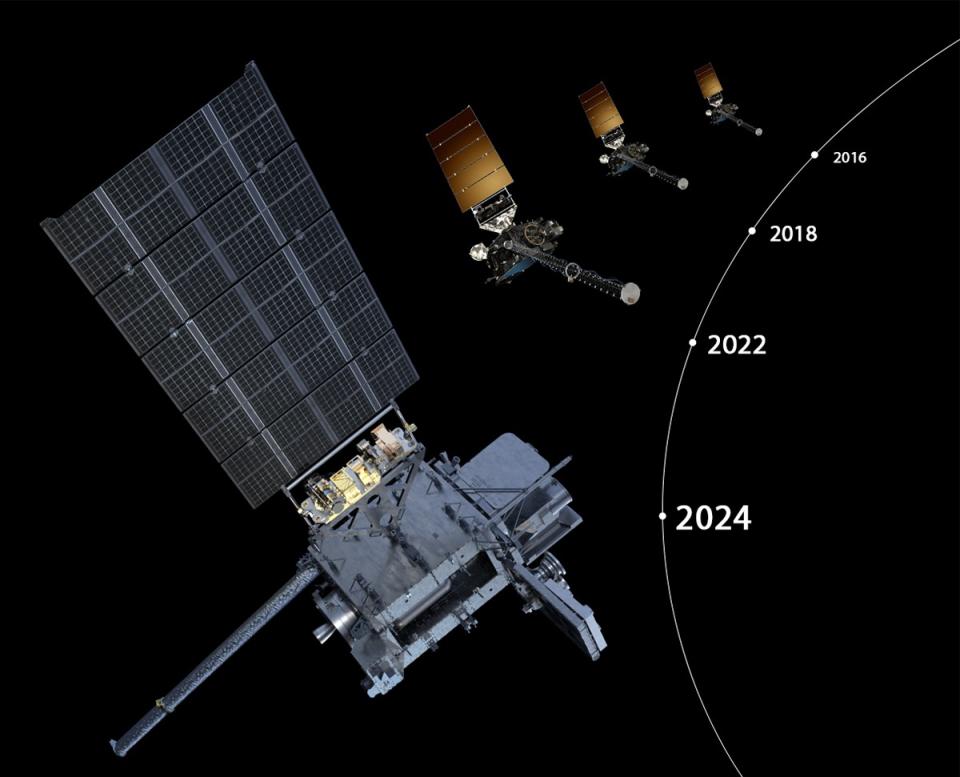

The latest constellation of the GOES family began in November 2016 when its first of four satellites, GOES-R, was launched into space. At that time, I was working at KEYT-TV in Santa Barbara, California, and had the opportunity to join exclusive feature as preliminary data became available to scientists across the United States.

I interviewed the staff of forecasters at the National Weather Service (NWS) Los Angeles office to find out how the variety of images and observations were useful in each of their different roles. Meteorologists shared how it was incorporated into their forecasts and used to issue alerts to warn the public of severe weather, and also how incredible it was compared to anything they had used before .

More than seven years later, with three of the four satellites in the series orbiting the Earth, scientists and researchers say that they are satisfied with the results and how the advanced technology was a game changer.

“I think it has really lived up to the hype in thunderstorm forecasting. Meteorologists can see the convection evolving almost in real time and this gives them an improved view of storm development and intensity, making better warnings,” John Cintineo, a researcher from NOAA’s National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL), told Space.com in an email.

“The GOES-R series not only provides observations where radar coverage is lacking, but often provides a strong signal before radar, for example when a storm is strengthening or weakening. I am sure there are many improvements others have done environmental forecasts and monitoring over the past decade, but this is where I’ve seen the most obvious improvement,” said Cintineo.

As well as helping to predict severe thunderstorms, each satellite has collected images and data on heavy rainfall events that could trigger flooding, detected low clouds and fog as it forms, and has made significant improvements to forecasts and on services used during hurricane season.

“GOES provides our hurricane forecasters with faster, more accurate, and more detailed data critical to assessing storm intensity, including cloud top cooling, convective structures, specific features of a hurricane’s eye, upper-level wind speeds, and lightning activity,” Ken Graham, director of NOAA’s National Weather Service (NWS) told Space.com in an email.

Instruments such as the Advanced Baseline Images (ABI) It has three times more spectral channels, four times the image quality, and five times the imaging speed of previous GOES satellites. The IS Geostationary Lightning Maps (GLM) It is the first of its kind in orbit on the GOES-R series that allows scientists to see 24/7 lightning and ground-to-cloud and cloud-to-cloud strikes.

“GOES-U and the GOES-R series of satellites provide scientists and forecasters with weather monitoring of the entire western hemisphere, at unprecedented spatial and temporal scales,” said Cintineo. “Data from these satellites is helping researchers develop new tools and methods to address problems such as lightning prediction, sea spray identification (sea spray is dangerous to mariners), severe weather warnings, and accurate estimation of cloud motion .The instruments from GOES-R also help improve forecasts from global and regional numerical weather models, through better data assimilation.”

Although similar to its siblings, GOES-U will be unique in that there are improvements to its instruments that have come from what scientists have learned from the three currently in orbit.

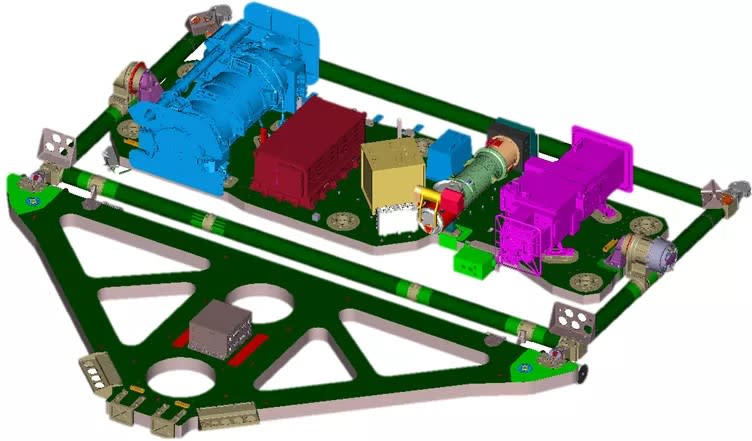

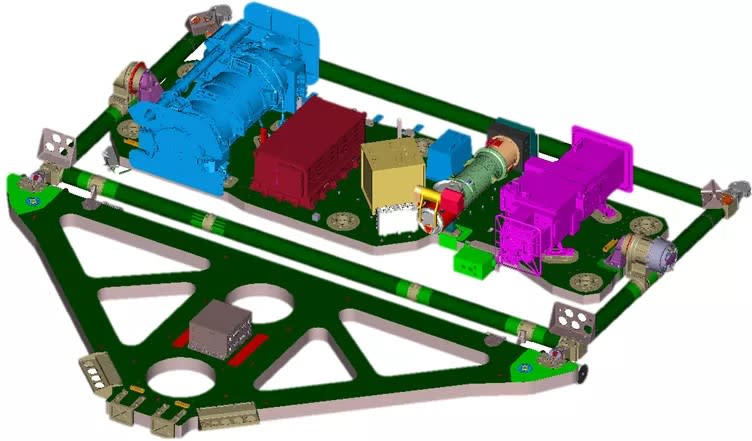

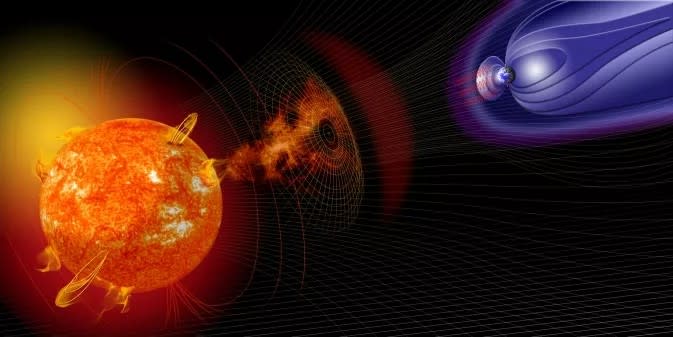

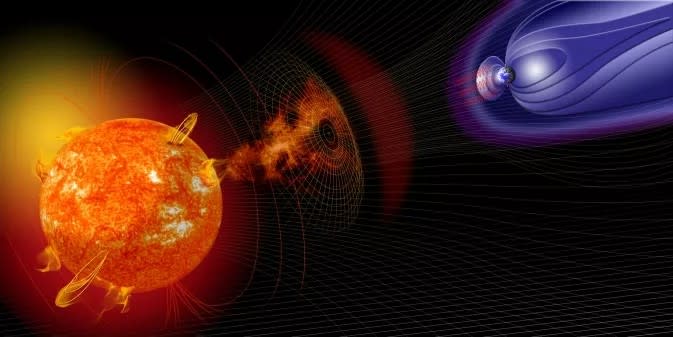

But what will separate GOES-U from the others is a new sensor on board, the Compact Coronagraph (CCOR), which will monitor the weather outside the Earth’s atmosphere, keeping track of space weather events that they could have an impact on our planet. .

“This is the first near-real-time operational coronagraph that we will have access to. This is a big step for us because until now, we have always relied on a research coronal instrument on a spacecraft that was launched quite some time ago,” said Rob Steenburgh, a space scientist at NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC), with Space.com on the phone.

“So this is exciting because I’m not going to wait now to download the data, because sometimes current coronagraph images are delayed. Sometimes we wait as long as four or eight hours, and every hour count when you are.” deal with coronal mass ejections (CMEs) that sometimes come to Earth and give us big geomagnetic storms like we had last month.”

RELATED STORIES:

— How to watch SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket launch NOAA’s GOES-U satellite on June 25

— This month’s launch of the GOES-U satellite will bring a solar activity monitor to space

– The 2024 hurricane season should be busy, NOAA says

Before forecasting space weather, Steenburgh was a terrestrial weather meteorologist, and he says how these next-generation satellites have dramatically changed the way scientists can make forecasts. He says improvements in technology since the 1980s have provided Earth and space weather forecasters with the tools they need to increase their confidence and improve forecast accuracy.

“Probably one of the biggest (changes) was the introduction of the Doppler weather radar, which is mind-blowing to me. It was a huge leap in capability, so I felt like I was part of the Golden Age of. meteorology,” said Steenburgh. “I moved into space weather around 2005 and have been very fortunate to see a very similar evolution in this field which has just been amazing.

“Now, I have over 16 and observation platforms that I did not even imagine with data quality in terms of temporal and spatial resolution beyond my wildest dreams soon. I am lucky to live in a Golden Age another,” Steenburgh said.