Recently I was invited to watch a game from one of the hospitality boxes at the new Tottenham Stadium. It was a cold night, and while we were sitting in the spacious armchairs giving uninterrupted views across the park, my host pointed out a switch in the armrest.

“Heated seats,” he said.

Not what we who were brought up in the old school could expect at a football game.

But then in the last few decades, everything has changed. Stadiums that were once death traps have transformed into comfortable multi-purpose entertainment destinations. When Everton move into their new Bramley Dock home, they will become the seventh club in the Premier League to have built state-of-the-art premises since the Millennium. Provided, of course, that they have not been re-admitted into the Championship.

At the heart of the stadium revolution was the global architectural partnership Populous. In the 30 years since their first UK project – the John Smiths Stadium in Huddersfield – they have designed the buildings that have come to define the way we look at sport. From Wembley and the Principality Stadium, through the Emirates and Tottenham, to Wimbledon Center Court and the grandstand at Ascot, they are behind much of this country’s new sporting infrastructure.

And not just in Britain. One of their own is the BBVA Monterrey Stadium in Mexico which will host matches at the next World Cup. As is the Narendra Modi Stadium in Ahmedabad, the largest cricket ground in the world and at the heart of the Indian city’s bid to host the 2036 Olympics. Not forgetting the magnificent Lusail Stadium in Qatar where Lionel Messi lifted the World Cup this time last year.

The next landmark on the skyline is Manchester United’s aging and crumbling home Old Trafford, as Telegraph Sport revealed on Boxing Day, Populous has already proposed a complete demolition and the construction of a new £2 billion stadium.

Earlier this month the company put on an exhibition of their work, and I was privileged to get a guided tour from the company’s managing director, Chris Lee, the man who said this week that a whole new stadium would be the best of the three current options – the others were a complete redevelopment or a minor makeover.

“Stadiums used to be functional exercises,” he explains, as we look at photographic evidence of Populous’ global reach. “Not anymore. They are now regarded as cultural assets.”

More than that. As it soon becomes clear as Liverpool’s abandoned old dock around Everton’s new home reappears, the stadium is not an end in itself today. It is the beginning of something.

“Sports venues were once considered bad neighbours,” says Lee. “The American model was to move them out of town, surrounded by car parks. Now they are engines of urban regeneration.”

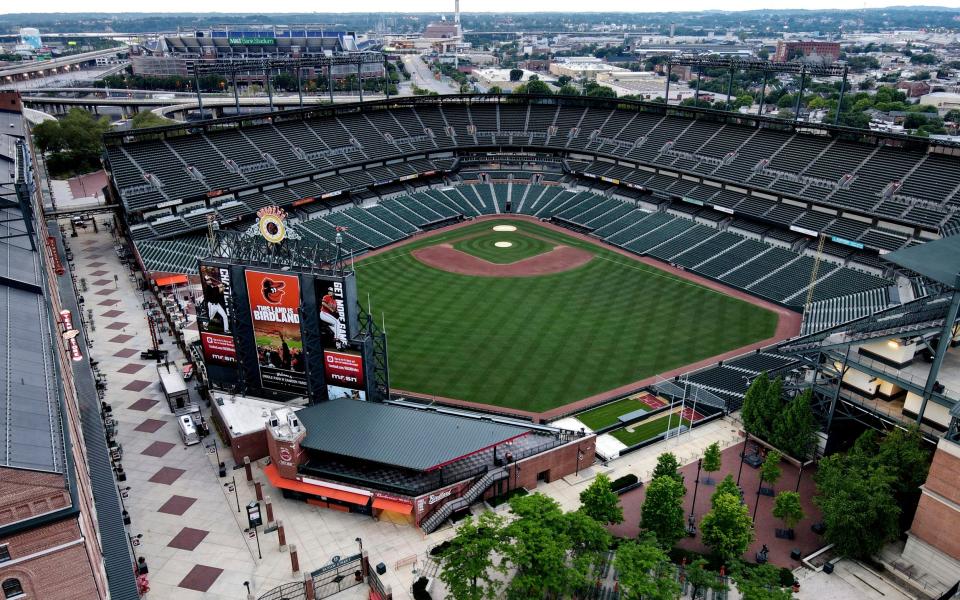

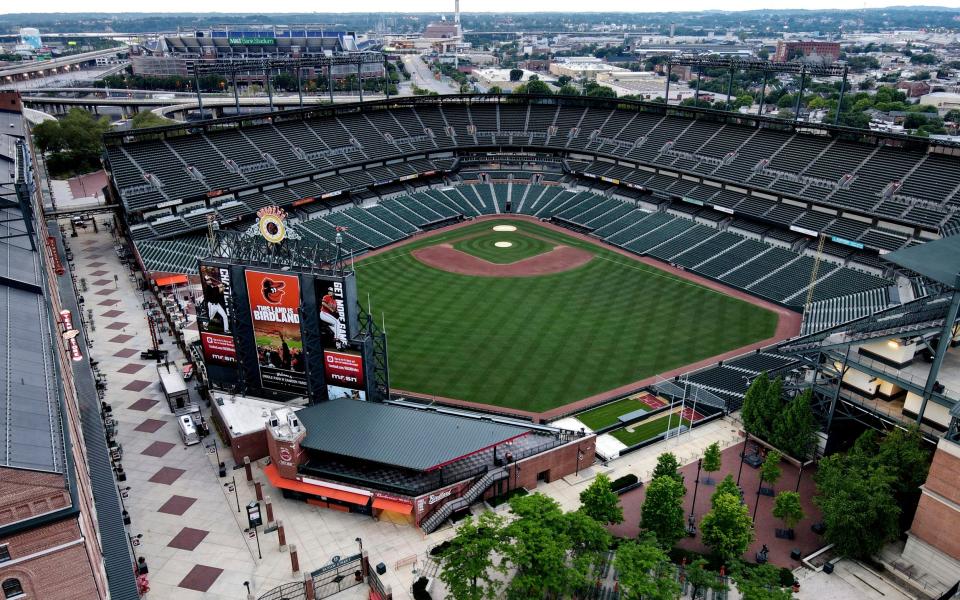

Baltimore in Maryland was the first place to recognize that a stadium could be used to develop seeding, when the new Orioles ballpark was built in Camden Yards; a neglected post-industrial part of the town centre.

“Since they’ve been there, the whole area has been completely revitalized,” says Lee. “And you can see it in this country. When we did the Emirates it was a vital part of a plan to link Lower Holloway with Islington, 4500 new homes are to be built around Spurs, Wembley is undergoing massive redevelopment of an area that was very wooriously decaying.

Whatever the wider development implications, however, these buildings are forward-looking places for fans. And even with that, there has been a shift in emphasis over the years.

“English football used to be guilty of seeing its audience as a captive audience, you know ‘we’ll treat you like we want to be treated and you’ll still come back’,” says Lee. “The change over the last 30 years has been the recognition that fans are customers with a choice.”

Although priority was given to a certain category of fans at first.

“Yes, I admit that in the early days the focus was on corporate facilities. The big move at Spurs was to say from the smallest seat to the most expensive seat, we’ll give you something.”

And at Spurs that is something substantial. Spacious food and beverage halls, great sight lines, improved acoustics: everything to create an experience.

“The design of the Tottenham Stadium focused on atmosphere, how to create an identity in a bowl of seats,” explains Lee. “Daniel Levy and I spent a lot of time travelling. We went everywhere, not ashamed to borrow bits we liked. Not only to sports venues, but to concert halls, theaters. Little pieces from all over have been put together in that building.”

Levy was practical in the process, sending a stream of emails, anxious things were done as best they could be. Especially in the stadium’s reputation: focusing on the energy of the North London derby, it had to seat more fans than the Emirates. Although Lee points out that the Spurs vice-chairman was not his only client who was keen to be involved every step of the way.

“When we did the new Ascot stand [which opened in 2006], The Queen was very strong. We had a monthly meeting with her, showing progress on design and construction. She had so much input. And it always solves the planning process when the client is the Sovereign.”

The late Queen was the Daniel Levy Ascot: who knew?

Great as it may be, even the Spurs Stadium is not the end of things. Innovation is relentless. The community is building a new Coop Live indoor arena near the Etihad in Manchester, which incorporates detailed acoustic engineering that will inform the design of the outdoor venues. And then there’s the Sphere – a Las Vegas amusement bowl designed by Lee and his colleagues.

“When we started that the technology that was needed wasn’t even inventable,” he says of the up-to-date sound and lighting systems. “And I think you saw at the recent Grand Prix in Vegas what that building can be.”

In fact it was the focal point of the race, with the cars spinning around what Lee described as the biggest billboard in the world. And the technical possibilities of the building represent a new future for watching sport. Spheres could soon be around the globe, showing footage of live events in the most immersive way possible. While the North London Derby takes place at the Tottenham Stadium, thousands of fans in Shanghai, Singapore and Arabia could be watching things unfold within their local Sphere, feeling, thanks to the sights and sounds projected, as if they really existed.

“The truth is, the future of sports watching is going to involve technology, a lot of technology,” says Lee.

Well, that and heated seats.