“Dune,” widely considered one of the greatest sci-fi novels of all time, continues to influence how writers, artists and inventors envision the future.

Of course, there are Denis Villeneuve’s visually stunning films, “Dune: Part One” (2021) and “Dune: Part Two” (2024).

But Frank Herbert’s masterpiece helped Afro-American novelist Octavia Butler imagine a future of conflict amid environmental disaster; inspired Elon Musk to build SpaceX and Tesla and push humanity towards the stars and a greener future; and it’s hard not to see a parallel in George Lucas’ “Star Wars” franchise, especially their fascination with desert planets and giant worms.

And yet when Herbert sat down in 1963 to begin writing “Dune,” he wasn’t thinking about how to leave Earth behind. He was thinking how to save it.

Herbert wanted to tell a story about the environmental crisis on our own planet, a world driven to the brink of ecological disaster. Technologies unimaginable only 50 years earlier have brought the world to the brink of nuclear war and environmental collapse; huge industries were sucking wealth from the land and spewing toxic fumes into the sky.

When the book was published, these themes were front and center for readers, too. After all, they were living after the Cuban missile crisis and the publication of “Silent Spring,” conservationist Rachel Carson’s landmark study of pollution and its threat to the environment and human health.

“Dune” soon became a beacon for the new environmental movement and a rallying flag for the new science of ecology.

indigenous wisdom

Although the term “ecology” had been coined nearly a century earlier, the first textbook on ecology was not written until 1953, and the field was rarely mentioned in newspapers or magazines at the time. Few readers had heard of the emerging science, and even fewer knew what it suggested about the future of our planet.

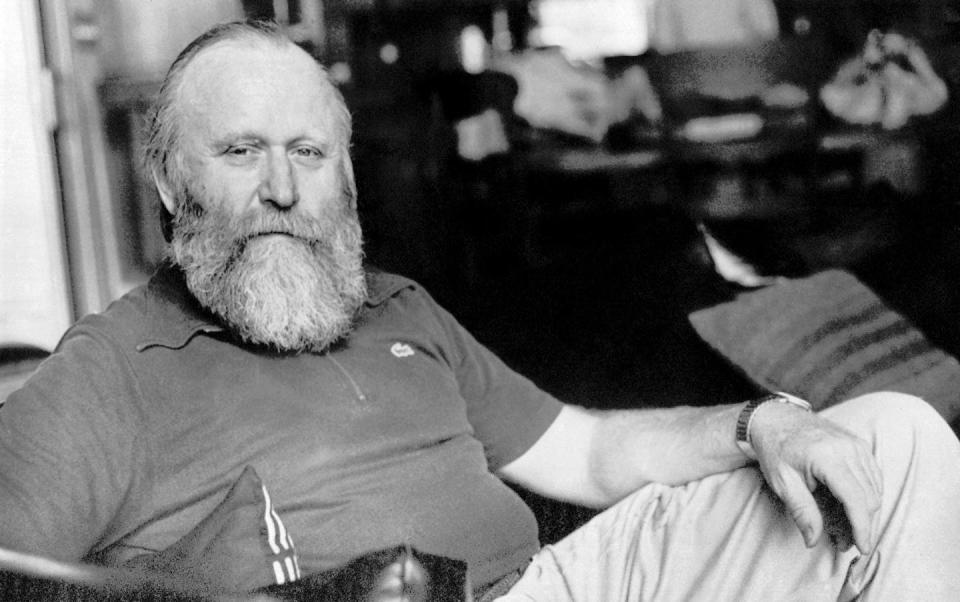

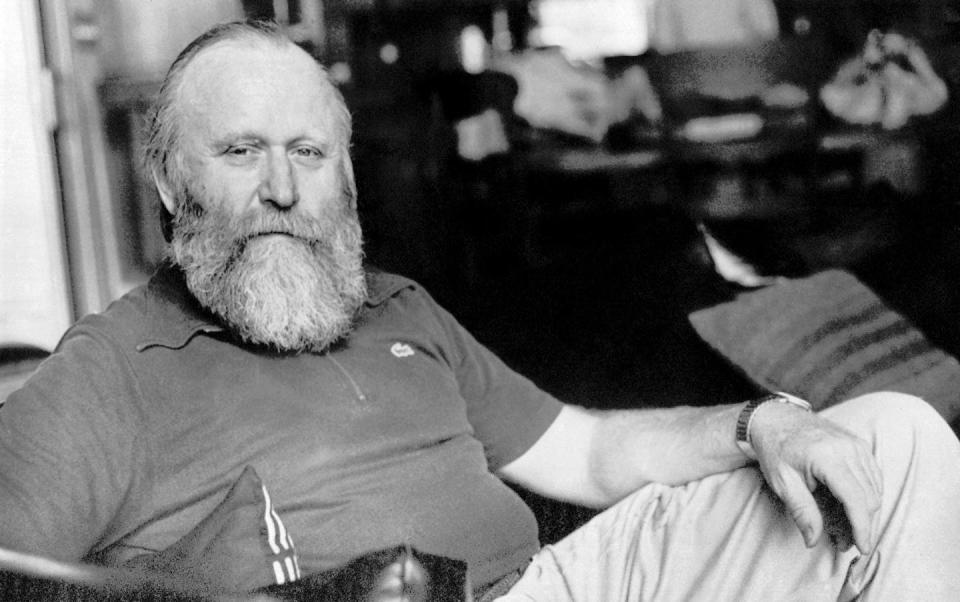

While studying “Dune” for a book I am writing on the history of ecology, I was surprised to learn that Herbert did not learn about ecology as a student or journalist.

Instead, the conservation practices of Pacific Northwest tribes inspired him to explore ecology. He learned about them from two friends in particular.

The first was Wilbur Ternyik, a descendant of Chief Coboway, the Clatsop chief who welcomed explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark when their expedition arrived on the West Coast in 1805. He was an art teacher and oral historian of the Quileute tribe. the second, Howard Hansen. .

Ternyik, who was also an expert field ecologist, took Herbert on a tour of the Oregon sand dunes in 1958. Here, he explained his work in building giant sand dunes using beach grasses and other deep-rooted plants to prevent the sand from blown. into the nearby town of Florence – terraforming technology described in detail in “Dune.”

As Ternyik explains in a handbook he wrote for the US Department of Agriculture, his work in Oregon was part of the effort to remediate European-colonized landscapes, particularly the large river jetties built by early settlers.

These structures disrupted coastal currents and created large expanses of sand, turning stretches of the Pacific Northwest’s lush landscape into desert. This situation is echoed in “Dune,” where the novel’s setting, the planet Arrakis, is similarly misplaced by the first colonists.

Hansen, who was the father of Herbert’s son, had studied the equally significant impact of logging on the Quiileute people’s homeland in coastal Washington. He encouraged Herbert to examine ecology carefully, giving him a copy of Paul B. Sears’ “Where There is Life” from which Herbert collected one of his favorite passages: “The highest function of science is to give us an understanding of consequences. “

“Dune” Fremen, who live in the Arrakis desert and carefully manage its ecosystem and wildlife, embody these teachings. In the fight to save their world, they expertly blend ecological science and Indigenous practices.

Treasures hidden in the sand

But the work that most influenced “Dune” was Leslie Reid’s 1962 ecological study “The Sociology of Nature.”

In this landmark work, Reid explained ecology and ecosystem science to a popular audience, illustrating the complex interdependence of all creatures within the environment.

“The deeper one studies ecology,” writes Reid, “the more evident it becomes that mutual dependence is a governing principle, that animals are bound together by unbreakable bonds of dependence.”

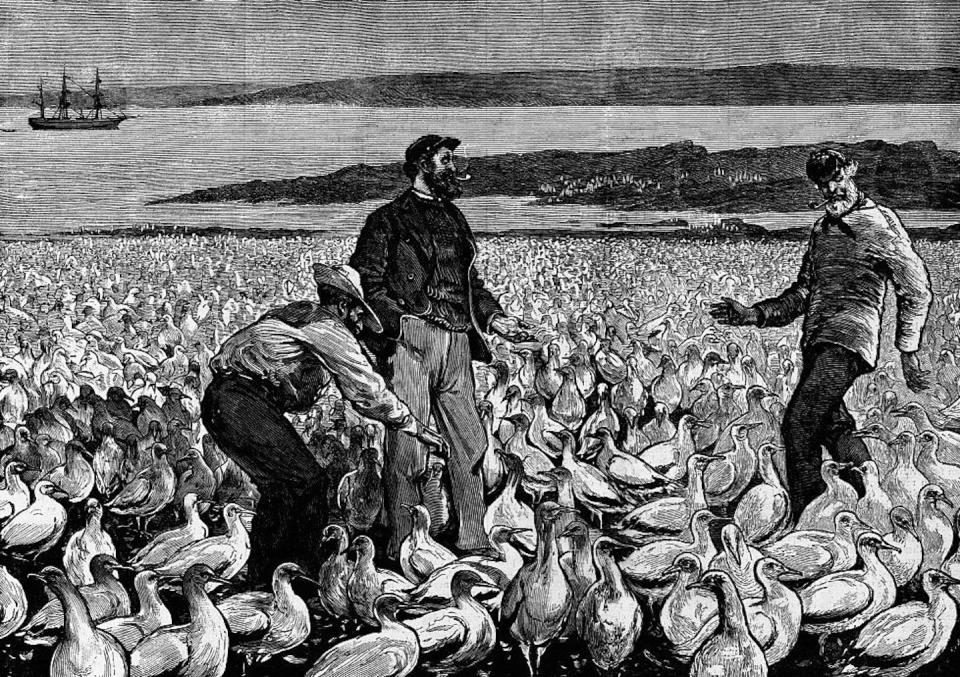

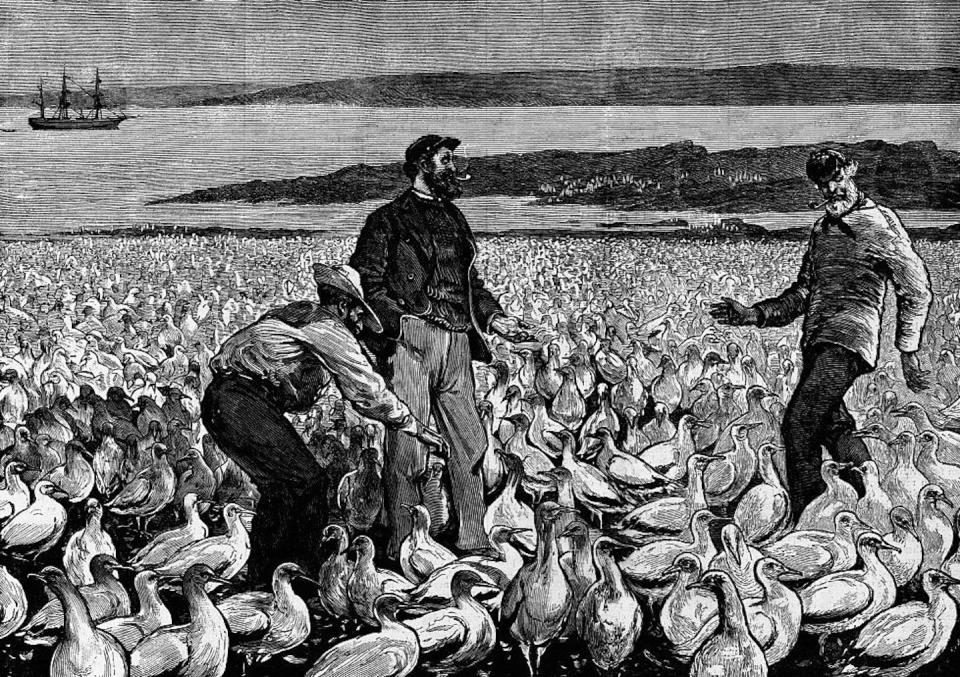

In the pages of Reid’s book, Herbert found a model of the Arrakis ecosystem in a surprising place: the guano islands of Peru. As Reid explains, the accumulated bird droppings found on these islands were ideal fertilizer. Home to mountains of dung known as the new “white gold” and one of the most valuable substances in the world, the guano islands became ground zero for a series of resource wars between Spain and some of its former colonies, including Peru, until the late 1800s. , Bolivia, Chile and Ecuador.

At the heart of the plot “Dune” is a battle for control of the “spice,” a valuable resource. Mined from the sands of the desert planet, it is a somatic food seasoning and hallucinogenic drug that allows some people to bend space, making interstellar travel possible.

There is a certain irony in the fact that Herbert concocted the idea of spices from bird droppings. But he was intrigued by Reid’s careful account of the unique and efficient ecosystem that produced a valuable – albeit malignant – commodity.

As the ecologist explains, frigid currents in the Pacific Ocean push nutrients to the surface of nearby waters, helping photosynthetic plankton to thrive. These support a great population of fish that feed many birds, as well as whales.

In early drafts of “Dune,” Herbert combined all these stages into the life cycle of giant sandworms, football-field-sized monsters that scurry through the desert sand and eat everything in their path.

Herbert imagines each of these monstrous creatures beginning as small photosynthetic plants that grow into “sand trout”. Finally, they become giant sandworms that gnaw the desert sand, spicing up the surface.

In the book and “Dune: Part One,” soldier Gurney Halleck recites a glorious verse commenting on this inversion of marine life and emerging regimes of extraction: “For they shall draw of the abundance of the seas and of the hidden treasure . the sand.”

‘dune’ revolutions

After “Dune” was published in 1965, it was enthusiastically embraced by the environmental movement.

Herbert spoke at the first Earth Day in Philadelphia in 1970, and in the first edition of the Whole Earth Catalog – a famous DIY handbook and newsletter for environmental activists – “Dune” was advertised with the tagline: “The metaphor is ecology. The theme revolution.”

In the opening of Denis Villeneuve’s first adaptation, “Dune,” Chani, a native Fremen who played Zendaya, asks a question that anticipates the violent conclusion of the second film: “Who will be our next oppressors?”

Paul Atreides, the white protagonist played by Timothée Chalamet, drives the pointed anti-colonial message home like a knife. In fact, both of Villeneuve’s films specifically elaborate on the anti-colonial themes of Herbert’s novels.

Unfortunately, the edge of their environmental criticism is blunted. But Villeneuve has suggested that he might adapt “Dune Messiah” into his next film in the series – a novel in which the ecological damage to Arrakis is stark.

I hope that Herbert’s immediate ecological warning, which resonated so strongly with readers back in the 1960s, will be unsung in “Dune 3.”

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. Written by: Devin Griffiths, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Read more:

Devin Griffiths does not work for, consult with, hold shares in, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and does not disclosed any relevant connections beyond their academic appointment.