The Biden administration has put a hold on pending decisions on applications for permits to export liquefied natural gas, or LNG, to countries other than US free trade partners. During this hiatus, which will last up to 15 months, the administration has pledged to look hard at economic, environmental and national security issues related to LNG exports.

Environmental advocates, who have expressed concern about the rapid growth of US LNG exports and their effects on the Earth’s climate, praised this step. Critics, including energy companies and members of Congress, argue that it threatens European energy security and energy jobs in the United States Emily Grubert, associate professor of sustainable energy policy at the University of Notre Dame and former official at Department of US Energy, which explains why large-scale LNG exports raise complex questions for US policymakers.

Is the US a major LNG supplier?

The US is now the world’s largest exporter of LNG. In November 2023, the most recent month with complete data, the US exported about 390 billion cubic feet of LNG, a record.

The United States has been a net exporter since 2017, with export volumes now equal to about 15% of our domestic consumption. This gas sells for higher prices than domestically delivered natural gas, but it also costs more to process and deliver. As of 2022, the US provided 20% of total global LNG exports.

Are there plans to export more LNG?

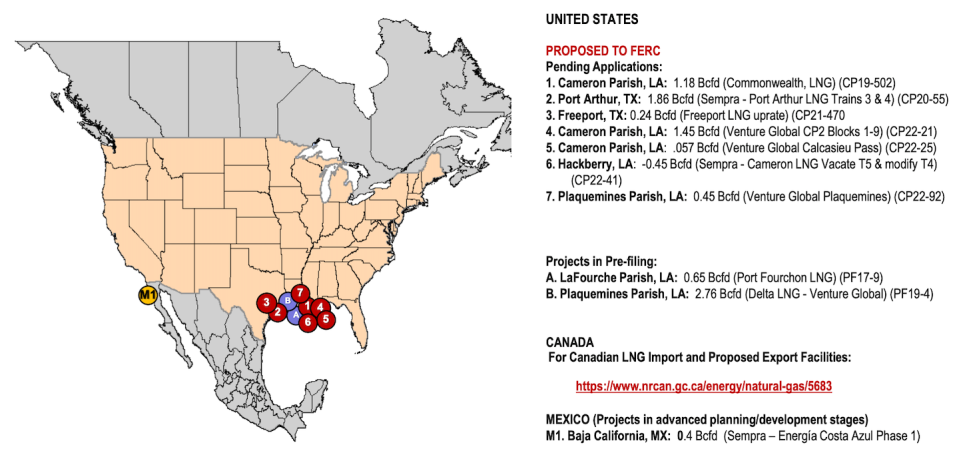

The US Energy Administration predicts that North American LNG export capacity – most of it from the US – is likely to double from current levels by the end of 2027. In the US, five LNG export terminals are currently under construction, and there is no impact on them. by the current break.

Requests for additional export terminals are under review. These are the applications for which decisions have been temporarily suspended.

How does LNG fit into fossil fuel transition?

LNG, and natural gas in general, has an uneasy place in the decarbonisation transition. Natural gas is a fossil fuel. When burned, it produces carbon dioxide which contributes to climate change.

Furthermore, natural gas that has been processed for use is essentially pure methane, itself a greenhouse gas. When natural gas leaks into the atmosphere from sources such as wells, pipelines or processing plants, it contributes to climate change. Since the mid-1800s, human activities – primarily, fossil fuel burning – have raised the Earth’s temperature by about 2 degrees Fahrenheit (1.1 Celsius) above pre-industrial levels. Methane has accounted for about 0.9 degrees F (0.5 C) of that warming above pre-industrial global temperatures.

LNG is not a transition from fossil fuel – it is a fossil fuel. Hypothetically, replacing LNG with more carbon-intensive fuels, such as coal or other natural gas supplies with higher methane emissions, could help reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the near future.

But there is debate about how much LNG is actually useful in that context, especially when it comes to whether LNG would encourage a switch from coal to gas, and if so, whether it is worth the long-term lock-in of fossil gas use. Meanwhile, investing in new LNG infrastructure means committing to operating these facilities for years, or planning to strand expensive assets by decommissioning them early.

LNG terminals also have a significant local impact. As well as methane, they emit large quantities of other air pollutants, including nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds. Tanker traffic to and from them can damage marshes and waterways. Building more terminals, especially in areas where energy facilities are already concentrated, raises important health and environmental justice concerns.

A transition to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions will require a commitment to actually transition from fossil fuels. In my view, it is unclear whether LNG deployment will achieve this goal if it is not done with a clear plan and mechanism to ensure that the gas is used only when it is needed and can support the elimination of emissions gradually.

What do you think this policy review should consider?

As I see it, the most important step is to develop a coherent national strategy for the role of natural gas in the US energy system, in line with the Biden administration’s aggressive goals of making the US electricity supply carbon-free by 2035 and achieve. a net-zero greenhouse gas economy by 2050.

Such a plan would require a plan to reshape the nation’s energy infrastructure to phase out the use of natural gas, along with coal and oil. In theory, it could include targeted deployment of gas resources to ensure energy needs are met while deploying zero carbon resources along the way.

I want the climate, health and energy consequences of allowing additional LNG export terminals to be made clear, and enforcement mechanisms in place to ensure that the US meets defined limits on climate and other pollution, and operating conditions. I would also like to see health and environmental justice issues deeply embedded in energy and climate decisions in general, and for LNG projects in particular.

These plants are primarily located in communities that have experienced high rates of illness, premature deaths and environmental damage due to hosting fossil fuel infrastructure for decades. Many have said they do not want further LNG development. I think that without clarity on where the US is going on this issue, it will be extremely difficult to make good decisions about LNG, and natural gas in general.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by Emily Grubert, University of Notre Dame

Read more:

Emily Grubert served in 2021-2022 as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Carbon Management and, later, as Senior Advisor in the US Department of Energy’s Office of Renewable Energy and Carbon Management, which has approval authority over LNG terminals. She was not involved in LNG decisions.