Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

How do they build things like underwater tunnels and bridges? – Helen, age 10, Somerville, Massachusetts

When I was a kid, I found a Calvin and Hobbes comic strip that asked one of my burning questions: How do they know the load limit on bridges? Calvin’s father (wrongly) told him, “They drive more and more trucks over it until it breaks. Then they weigh the last truck and rebuild the bridge.”

Several years later, I am a geotechnical engineer. That means I work on any construction projects that involve soil. Now I know the real answers to things people wonder about infrastructure. Often, like Calvin’s father, they think about things from the wrong direction. Engineers do not usually determine the load limit on a bridge; instead, they build the bridge to carry the burden they expect.

It’s the same as another question I hear from time to time: How do engineers build things underwater? They usually don’t build things under water – instead they build things that go under water. This is what I mean.

Underground construction, below the water

Sometimes when you’re building underwater, you’re actually building underground. It is not about the water you see on the surface but what is around the structure you are building yourself.

If what you’re building is surrounded by rock or soil, that’s usually underground construction – even if there’s a layer of water above it and that’s what you see above.

Underground construction usually uses powerful tunnel-boring machines to directly excavate soil. This machine is often called a mole for a reason. Like the animal, it creates a tunnel like hole by digging horizontally through the ground, removing the excavated material behind it. Done carefully, this method can successfully build a tunnel through the ground under a body of water that can be lined and reinforced.

Engineers used this method to build the Tunnel, for example, a railway tunnel under the English Channel that connects England and France.

Although modern machinery is quite advanced, this method of construction began about 200 years ago with the tunneling shield. Originally, these were temporary support structures that provided a safe space from which workers could dig. New temporary structures were built deeper and deeper as the tunnel grew. As the designs improved with experience, the shields were built to be mobile and eventually evolved into the modern tunneling machine.

Construction on dry land before moving into place

Eventually some structures will be surrounded by water, resting on a river or ocean bed. Fortunately, engineers have some tricks for building bridges and tunnels that have components in direct contact with the water.

Underground construction is dangerous and difficult to access. Dealing with water poses additional challenges. Although soil and rock can be pushed aside to create a stable opening, water will always move in to fill any gap and must be pumped continuously.

People, materials and machinery don’t really work well under water, either. Humans need a constant supply of air. Concrete is difficult to submerge, and some materials only work on dry land. And since gas engines depend on air to operate, underwater equipment is very limited.

Some smaller tasks – aligning and connecting pre-built sections of the tunnel or inspecting to make sure nothing was damaged by the dive – are carried out under the waves, but most construction is unlikely. Once the structure is in place, there is continuous monitoring and assessment underwater.

Because people generally can’t build underwater, there are two options: Make the building outdoors and move it underwater, or temporarily change the underwater site to a dry one.

For the first option, crews usually build parts of the structure on dry land and then put them in place. For example, the Ted Williams Tunnel in Boston was built in sections in a shipyard. Workers dredging the tunnel’s future path in Boston Bay, clearing mud and other debris out of the way. Then they placed the sealed sections along the prepared trench. Once the sections were connected, they opened the ends of the sections to create one long continuous tube. Finally, the tunnel was covered with soil and rock. Very little of the construction process was done underwater.

In other cases, for example in shallow water, construction workers may be able to build directly from the surface. For example, workers can drive shore retaining walls made of sheet metal into the soil directly from a barge, without diverting the water.

The water is temporarily cleaned away

The second option is to get rid of the underwater problem entirely.

Although creating a dry site at the bottom of the water is difficult, it has a long history. After leading the sack of Rome in 410 CE, Visigoth king Alaric died on his way home. In order to protect his magnificent burial from grave robbers, Alaric’s family temporarily diverted a local river to bury him and loot him in the riverbed before letting the river pass.

Today, a project like this would use a coffer dam: a temporary waterproof enclosure that can be pumped dry to provide an open and safe site for construction. Once the area is enclosed and pumped free of water, you are in the realm of regular construction.

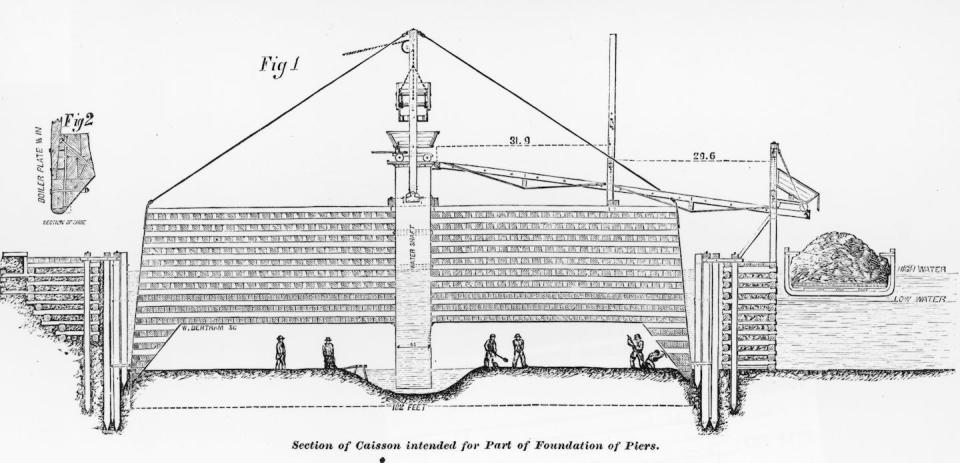

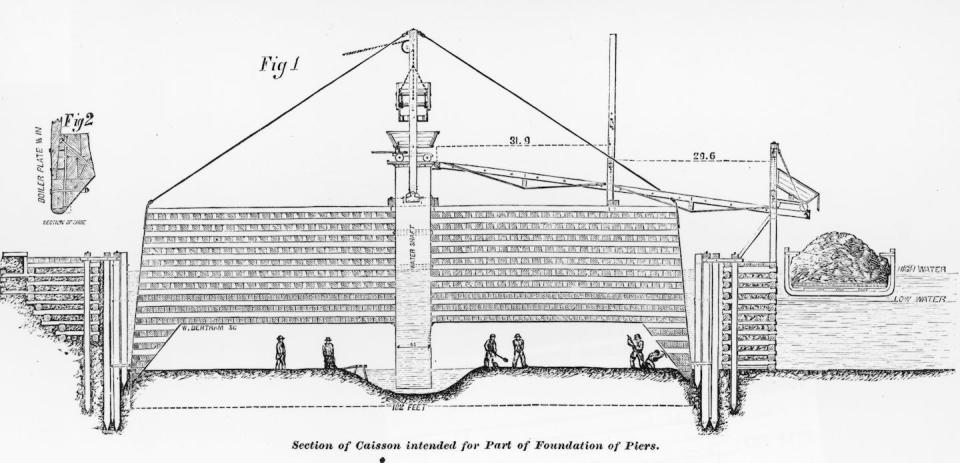

Using a caisson is another way to provide a dry area on a site that is normally flooded. A caisson is usually a prefabricated and watertight structure, shaped like an upside-down cup, that a crew sinks into the water. They keep pressure on it to make sure the water doesn’t flow in. When the caisson is on the floor of the body of water, the air pressure and pumping keeps the site dry and allows construction workers to build inside. The caisson becomes part of the finished structure.

Brooklyn Bridge pier builders built using caissons. Although the caissons were structurally safe, the difference caused stress to many workers, including the chief engineer, Washington Roebling. He developed caisson disease – commonly known as decompression sickness – and had to retire.

Building underwater is a complex and difficult task, but engineers have developed a number of ways to build underwater…often by not building underwater at all.

Hello, strange children! Have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you think too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we’ll do our best.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Ari Perez, Quinnipiac University

Read more:

Ari Perez does not work for any company or organization that would benefit from this article, does not consult with, shares in a company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has not disclosed any material relationships beyond their appointment academic.