Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

I have a question about ice on the Moon. How is this possible? – Olaf, age 9, Hillsborough, North Carolina

We are lucky to live in a world of water. More than 70% of the Earth’s surface is covered by water.

The Earth is about 94 million miles from the Sun. That is within the Goldilocks zone: the place in our solar system where a planet has the right temperature for water to exist in the oceans and rivers as liquid and as ice in the north and south poles.

Earth also has an atmosphere more than 6,000 miles (9,650 kilometers) thick filled with oxygen for us to breathe. This atmosphere, along with a giant magnet at the center of the Earth, helps protect us from the sun’s harmful radiation, mostly the solar wind and cosmic rays.

But the Moon hardly looks like a water world, or even a place with a few ponds. It has lost an internal magnet and an atmosphere so weak that there is little vacuum. There are no clouds or rain or snow, but a sky that is nothing but the darkness of space, with a surface baked by the Sun. The Moon’s temperature reaches 273 degrees Fahrenheit (134 Celsius) during the day and goes as low as -243 F (-153 C) at night.

But as scientists who study space and work to develop technologies that look for water, we can say definitively: Yes, the Moon has water.

The discovery

For a long time, astronomers and other scientists thought it unlikely that the Moon had water. After all, the Apollo astronauts brought back many rock samples from the Moon, all of them dry, with no detectable water.

But recent visits by spacecraft have shown that there is some water there. In 2009, NASA launched a spacecraft – the Lunar Crater Observation and Detection Satellite, or LCROSS – into the lunar surface, inside the Cabeus crater. When that happened, water ice was expelled.

This confirmed to scientists that there was water ice at the bottom of the craters. But it will be difficult to determine how much water there is. The 10,000 or so lunar craters are basically large holes, with areas so shaded that the Sun does not shine inside. These places are really cold, well below -300 F (-184 C). Once these frozen water molecules get stuck in the craters, they stay pretty much forever, unless some heat or energy releases them. They are unlikely to evaporate naturally or evaporate – it’s too cold there.

But that does not mean that water is only stored in craters. In 2023, scientists using SOFIA, the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, looked for water on the surface of the Moon in areas that were not as cold as the craters. And they found it – not on top of the soil, but probably inside the soil grains.

No one yet knows how much water the Moon has or how deep it goes. But one thing is certain: There is much more than scientists first thought.

Comets and volcanoes

How did the Moon get its water? No one is sure yet, but there are several theories.

Moments ago, comets—which are basically frozen, dirty snowballs—crashed into Earth, leaving behind their comet water. That’s one of the ways the Earth developed its oceans; maybe that’s how the Moon got some of its water too.

Other scientists think that ancient volcanoes on the Moon released water vapor when they erupted billions of years ago. Eventually, that vapor descends to the surface as frost. Over time, layers of that frost accumulated, especially at the poles; perhaps much of it found its way inside lunar craters as ice.

Drinking water for astronauts

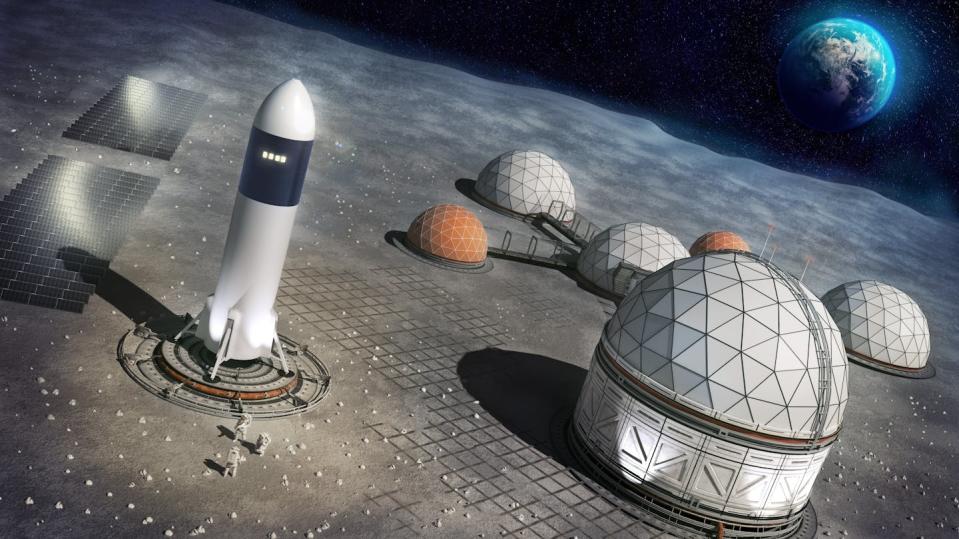

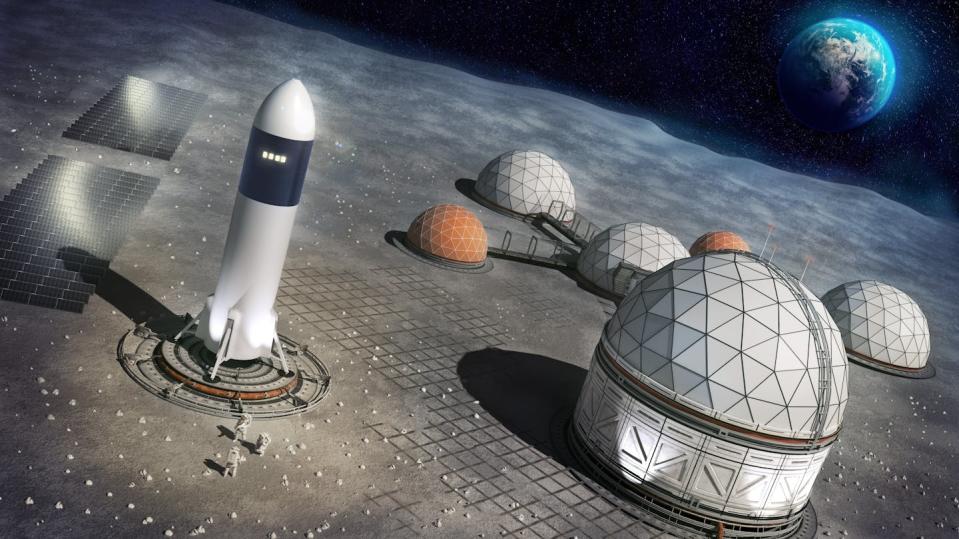

Water is heavy. It would be expensive to transport it to the Moon by spacecraft. So it makes more sense for astronauts to figure out a way to use the water that is already on the Moon.

But the water of the Moon is not drinkable as it is; there would be small pieces of lunar soil and possibly other molecules mixed in with it. Astronauts living in lunar colonies would have to purify any water they collected. This is a tedious process that would require a lot of effort and resources.

There is a plan to drill for the water and search for it, the way people hunted for gold underground during the 19th century gold rush. The analogy is not a bad one – water on the Moon could eventually be more valuable than gold on Earth.

And not just to drink. Water, of course, is two parts hydrogen, one part oxygen; it can be split. It’s a win-win: Astronauts can use the hydrogen for rocket fuel and the oxygen for breathable air. Using the Sun as a power source, water splitting is probably possible.

Returning to the Moon and establishing a permanent base are huge commitments that require decades of work, billions of dollars, the cooperation of many nations, and many new technologies yet to be developed. But as the world enters this dramatic new chapter of space exploration, pioneers risk destroying or contaminating a unique environment that has existed for billions of years – and many scientists feel a great responsibility not to. repeating our painful lesson. learning now here on Earth.

Hello, strange children! Have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you think too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we’ll do our best.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. Written by: Thomas Orlando, Georgia Institute of Technology; Frances Rivera-Hernández, Georgia Institute of Technologyand Glenn Lightsey, Georgia Institute of Technology

Read more:

Thomas Orlando receives funding from NASA and DOE.

Frances Rivera-Hernández and Glenn Lightsey do not work for, consult with, own shares in, or receive funding from, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations to, any company or organization that would benefit from this article. their academic appointment.