It’s a gray spring morning in London, and sitting on a pavement in Covent Garden is a box containing a witch’s head.

Or rather, parts of one. The head is in pieces as a whole, it would not fit: it is about eight feet high and wider still, with eyes as big as coals, teeth like bricks, and a huge nose sticking out from under the cover like a finger, at Click here for an inside look.

Fans of Studio Ghibli animation will immediately recognize it as Yubaba from Spirited Away, the nurse usually found upstairs in the magical bathhouse of that 2001 film. This year, however, the old girl is on tour.

After a sell-out run in Tokyo and a series of Japanese cities, the stage adaptation of Ghibli’s Oscar-winning animated fantasy is taking up residence at the London Coliseum. Around 70 puppets, many of them huge, are being wheeled inside the theater like gods on palanquins, and Blu-backed with bilingual signs on the backstage corridors: dressing rooms this way, canteen that.

Unlike the (unrelated) Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of My Neighbor Totoro, which has just finished its second season at the Barbican and will transfer to the West End next year, Spirited Away first opened in Japan, and it will be done here by its original cast. . However, moving from the UK is a homecoming. The show is directed and adapted by RSC and National Theater veteran John Caird, whose original production of Les Misérables in 1985 ran for 34 years in London’s West End. His creatures were created by Toby Olié, the puppeteer behind War Horse. Its stage designer is Jon Bausor, also of CSI, who designed the opening ceremony of the 2012 Paralympic Games.

It was probably invented up the road, in a church hall in Dalston. Caird had pitched the play to Spirited Away writer and director Hayao Miyazaki – more on that later – shortly before the pandemic, and by the time he could start working on it, he was back in the UK, as of the theater (and others). ) stopped.

Six months before rehearsals were to begin in Tokyo, Caird, Olié and Bausor met regularly in the vaulted upper hall of St. Barnabas to get their heads around the task of bringing Miyazaki’s extraordinary creation.

for life.

The most obvious challenge was the film’s supernatural menagerie, inspired by the kami, or “local gods”, of Japan’s native Shinto religion. (Olié built miniature prototypes of these in his workshop.) But they would have to make dramatic sense out of his oddly shaped plot – conceived, as in all Miyazaki’s films, as a series of hand-drawn pictures rather than words. on a page.

Focusing on a young girl named Chihiro who reluctantly accepts a job at a magical spring resort, it’s an Alice in Wonderland story as only Miyazaki could tell it: a child reckoning with the strangeness of the world on the way to adulthood but also wanting it resolutely. recreate her in his image, even as he conspires to remake her in his own image. To the layman, it also looks like a cultist’s nightmare, with its soaring dragons, raging waters and tumbling vertical drops that could not be recreated on stage.

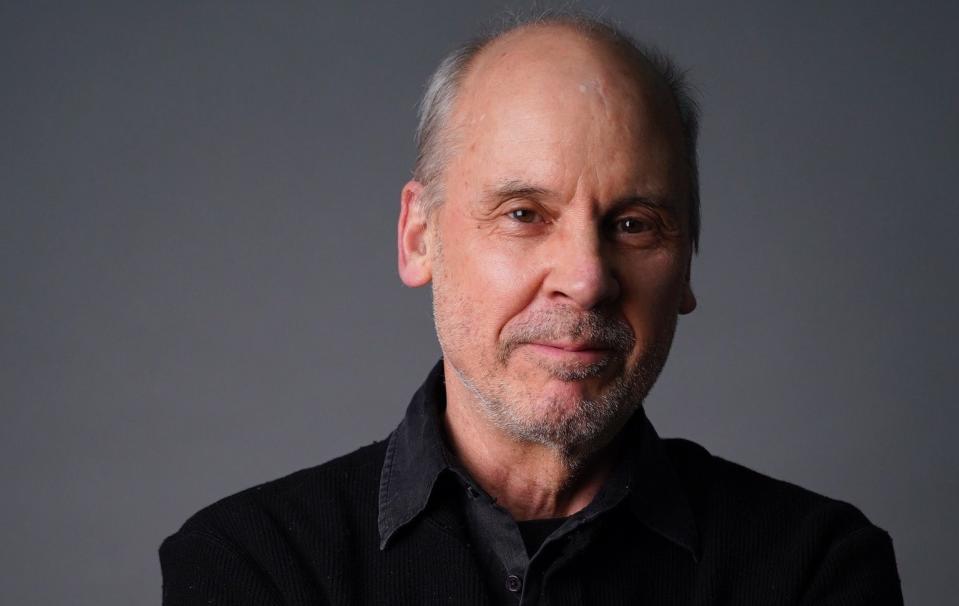

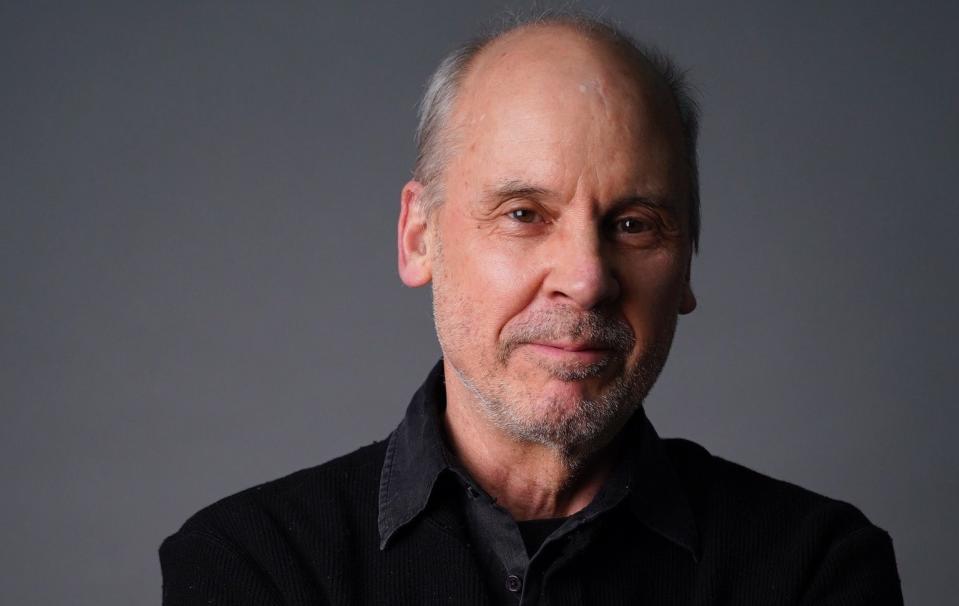

“It’s interesting that you use the word ‘impossible’,” Caird, who is 75, said over tea in his office across the road from the theatre. “Every day during practice, I want to start telling the team and the team: ‘Today’s task is impossible…'”

For Caird, the fog of the impossible began to clear when he connected Miyazaki’s masterpiece with noh – the classic Japanese form of hidden theater, which also features gods and ghosts. The grand entrance to Spirited Away’s bathhouse reminded Caird of the wooden noh stage, a sacred space accessed by performers via a bridge – and suddenly, from 700 years in the past, it had the elements of its set. Similarly, for the creatures, Caird and Olié drew from bunraku, a traditional Japanese puppetry in which performers who can make their own acrobatic movements part of the act bring life to the elaborate mannequins.

Friends have been wanting to do something Japanese for a while. Since 2007, he has directed several productions in Tokyo, but all of them had a Western basis: Les Misérables, of course; a bit of Bernstein and Wilde; a lot of Shakespeare. So when entertainment conglomerate Toho asked him to come up with a new project for the capital’s massive Imperial Theatre, Spirited Away was what sprung to mind.

He had seen the film when it was first released in the west, but didn’t think about adapting it until Toho’s offer came in, and the noh stage brainwave came. Then came the question of convincing Ghibli that it would work. Caird decided to meet with Joe Hisaishi, the famous composer of the film’s score, to seek permission to use his music in the show. (Hisaishi was so excited at the thought of finding an audience overseas, his only suggestion was that they give up on the Japanese run and start in Europe.) But before that, b A meeting had to be organized at the Ghibli headquarters in Tokyo in the leafy suburbs of Europe. Mitaka, where Caird and his producer met Toshio Suzuki, one of the co-founders of the studio.

“About 30 seconds after we entered Suzuki-san’s office, Miyazaki himself entered, wearing his work apron, and sat down,” Caird recalls. “We didn’t expect him to be with us at all, but I knew he was expected to be able to make a shot at that moment.”

Much to Caird’s surprise, it only took Miyazaki a few minutes to give his blessing to the project: “He seemed to want to get to the part of the conversation where I explained how we were going to do it.” They talked for an hour or so about the film’s inspirations, including the Shimotsuki festival held every Christmas in a corner of the Japanese Alps, where priests purify water by boiling it in iron pots and invite for gods from far and near come and bathe.

They also discussed the central role of Kaonashi, or No-Face: a masked ghost who becomes Chihiro’s most troublesome customer, who ends up swallowing guests and other employees.

“Suzuki reminded Miyazaki that he was barely in the first draft of the film,” Caird explains. “And he was brought in not to create a villain – something I’ve always admired in Miyazaki’s work is that there are no good or bad characters – but to make sense of Chihiro’s own journey; to encompass all the problems she had to solve.”

Perhaps Caird’s biggest problem was the pandemic. Even when the crisis eased, he was the only western member of Spirited Away’s creative team who was allowed to re-enter Japan, thanks to the country’s strict travel controls. That meant rehearsals had a heavy Zoom component, which was further complicated by the multiple time zones: “There was only about an hour each day when all the creative teams in Tokyo, the UK and America were awake, ” says Friend.

However, the Japanese cast and crew were more than up to the task. “Their work ethic is amazing. You have to insist that they take a day off every week, and when the practice is over they go home.”

Back in the Coliseum, the hall is buzzing with industry. The subtitle screens are being tested. The stage turns noh-like on the spot. The puppets are sitting (or, in the larger cases, lying) patiently in the stalls. Even ten years ago, the idea of a live-action Miyazaki adaptation packing out this 2,300-seat venue would have been absurd, but Card is confident that theatergoers will bounce back.

Last year, he went to see Hisaishi perform with the BBC Concert Orchestra at Wembley Arena, conducting some of the most iconic pieces from his Ghibli scores. “It was just amazing,” he says. “12,000 people, so many of them young, are all enjoying this work that has been little known for years in this part of the world. I remember looking around and thinking, ‘Our audience is here.’”

Spirited Away is at the Coliseum, London WC2 (spiritedawayuk.com) from 30 April to 24 August