Françoise Hardy, who has died aged 80, was an intoxicating romantic French chanteuse and heartthrob from the early Beatles era; one of her home country’s biggest “yé-yé” stars, she enjoyed a modest string of British hits in the mid-1960s, many of them noble and soulful ballads such as Tous les Garçons et les Filles, Et Même and All. Over the World, before her comeback 30 years later with Le Danger (1996), an album that placed her sensual voice and mysterious French lyrics in a contemporary soft rock setting.

She wrote most of her material herself, which was unusual in the 1960s for any pop star, let alone a woman. No matter how loud her songs were, they often expressed a kind of dreamy sadness. “I walk down the streets, my soul is sad,” ran one clear line in Tous les Garçons.

Such charm was in stark contrast to the edgy style, race and alluring beauty that made her the French cover girl of the 1960s. It was a combination that made a generation of young men on both sides of the English Channel fall in love with her – or more accurately, as critic Sean O’Hagan suggested in The Observer, “with her belief that the praise songs”.

Among the many men who idealized her was Salvador Dalí, with whom she ate ortolans, a French sweet, for the first and only time. David Bowie admitted he was “passionately in love with her”, Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones tried and failed to woo her, Mick Jagger described her as his ideal woman, and Bob Dylan paid tribute to her in a scribbled poem on a record sleeve.

He need not have bothered. “I wasn’t interested in him as a man, but as an artist,” she told The Daily Telegraph in 2005. “He took me to his hotel room after inviting me to a show in Paris and played me two tracks was not. still released … but it wasn’t very attractive.”

In her early years Françoise Hardy worked with Serge Gainsbourg; after her 1990s revival, she duetted with Damon Albarn, Iggy Pop and Julio Iglesias. She also loved the music of the Jesus and Mary Chain and Cigarettes After Sex, the Brooklyn cult band whose sound, she said, “I’ve been searching for my whole life”.

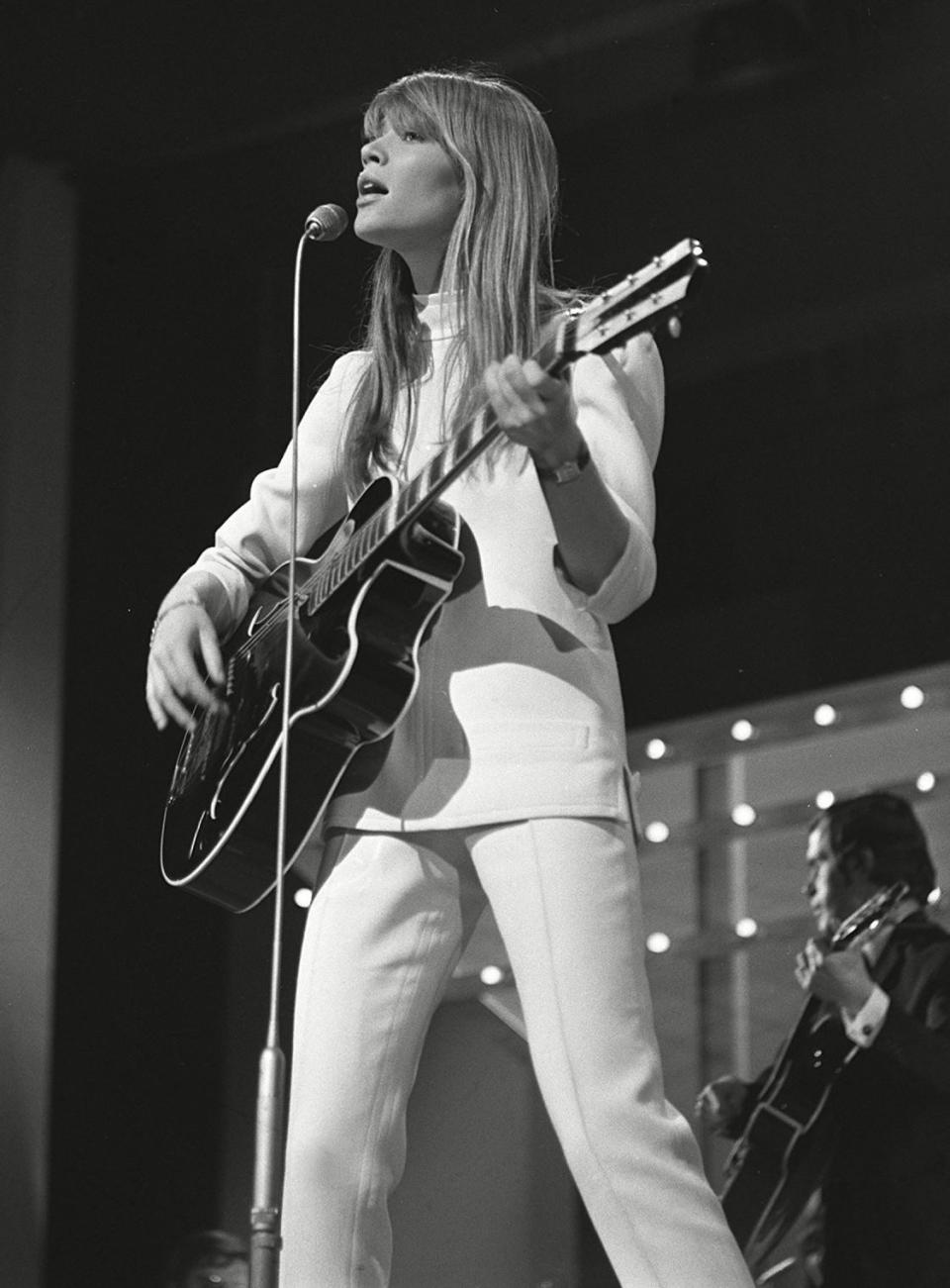

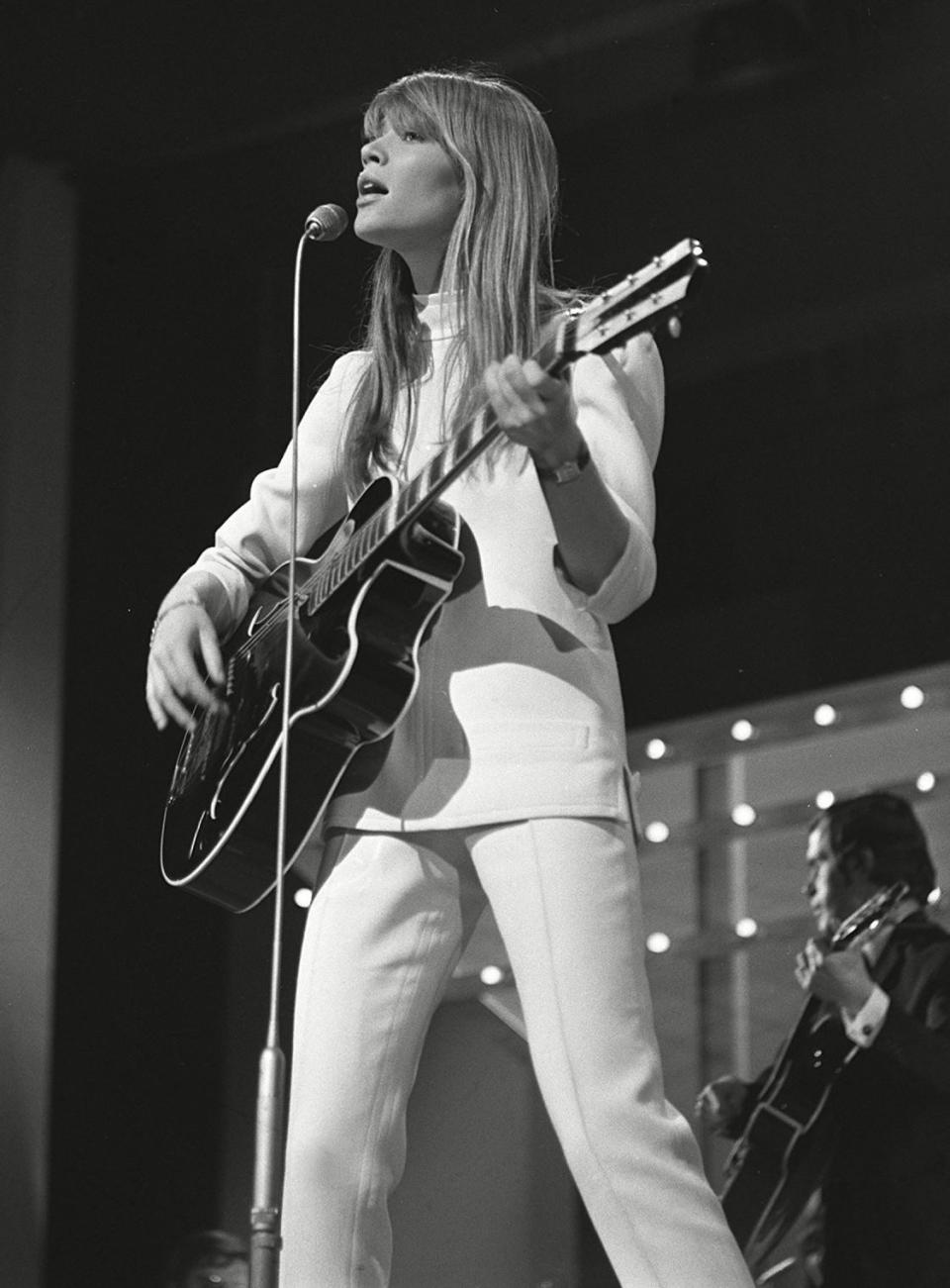

She had long since abandoned live performance, and felt that neither her voice nor her stage manners satisfied it. She finally made an appearance in 1967, including one at the Savoy Hotel in London where she wore a metal dress designed by Paco Rabanne that weighed 16kg despite her short stature. “If I could sing like Céline Dion, it would be different,” she once said, as self-critical as ever.

Françoise Madeleine Hardy was born during air raids in Nazi-occupied Paris on 17 January 1944, the eldest of two daughters of Madeleine Hardy, an accounts clerk, and her married lover, Étienne Dillard, who was absent from the party. mostly during his daughter’s childhood.

However, he insisted that Françoise and her sister, Michèle, who was later diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, were educated at Institution La Bruyère, a Catholic school run by the nuns of Trinity, where the shame of being from a single-parent family was created. them. a severe distrust of her that decades of fame and fortune have not yielded.

Her early stomping ground was a quarter of the ninth arrondissement called La Trinité, with its own claim to chanson fame. This is the apartment of the parents of Lucien Ginsburg, as Serge Gainsbourg was then known, and elsewhere in the quarter were Jean-Philippe Smet (or Johnny Hallyday) and Claude Moine (Eddy Mitchell of the Chaussettes Noires), two of whom Hardy remembered at the forefront of the place. bands of proto-rockers.

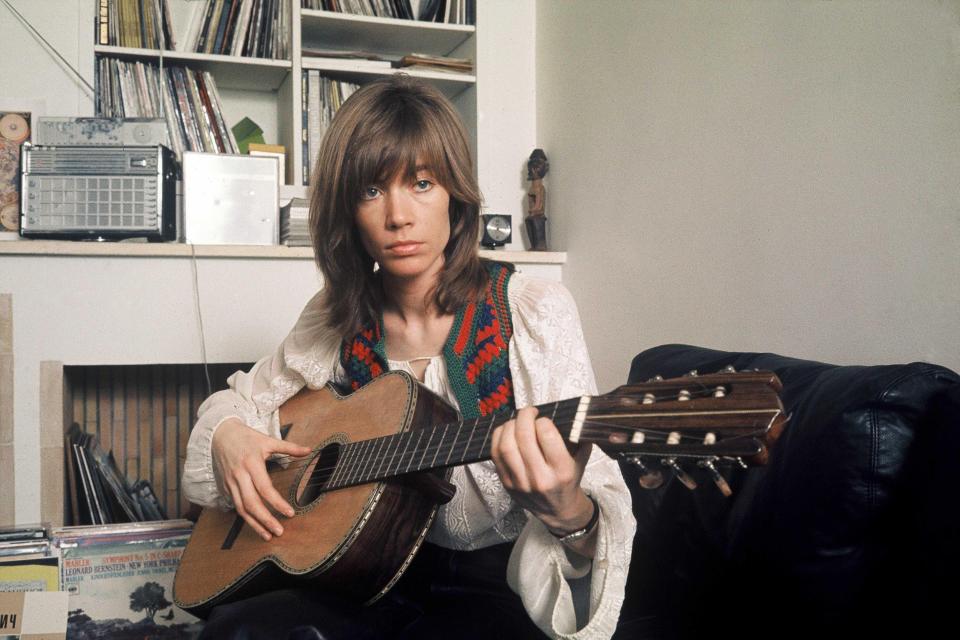

In 1959 her father reappeared to present her with a guitar as a reward for achieving her baccalaureate. Inspired by Salut les Copains, a radio program aimed at teenagers that aired on Europe 1 and would become the key to the French “yé-yé” wave inspired by the Beatles, she taught herself three chords. Soon she was using songwriting as a form of therapy, composing an endless series of numbers.

Signed by Vogue Records in 1961, she recorded Tous les Garçons, her own composition, during “three hours with the four worst musicians in Paris”. When she returned from her holiday in Austria the following summer she found that she had won and by mid-1963 sales of Tous les Garçons had reached two million copies, and the French press noted that she had sold more records in 18 months than Edith Piaf. did in 18 years.

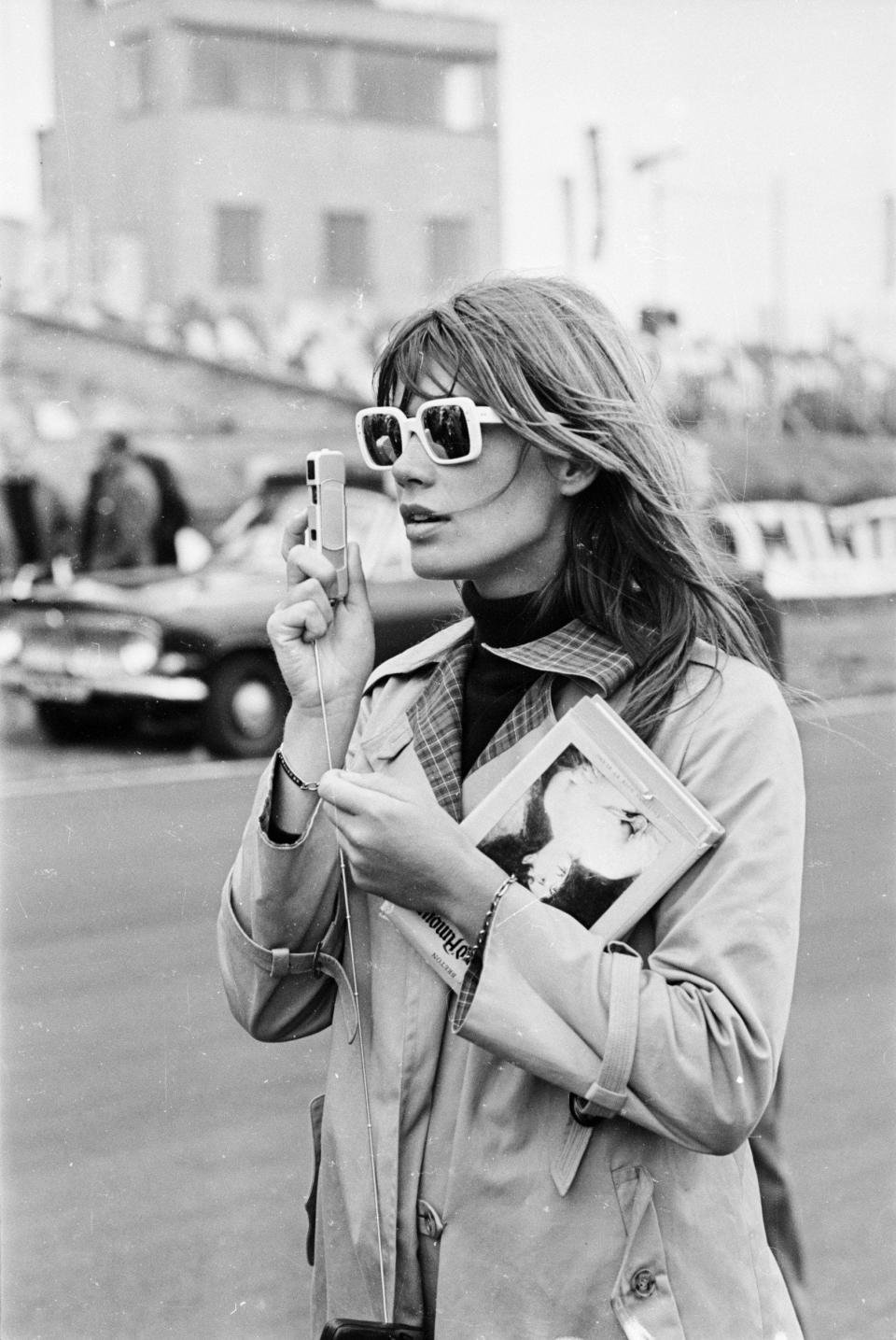

Roger Vadim, the film director credited with creating Brigitte Bardot, took her under his wing, promising to maintain her “girl next door” image, although her long straight hair was tied up almost immediately, a dress was where slacks and lack thereof. make-up correction. She appeared in Château en Suède (1963), a sex comedy set in a Swedish castle, and a handful of other films including the John Frankenheimer sports drama Grand Prix (1966), Frankenheimer having seen her leaving a club night in London, but she never followed. serious acting career.

Françoise Hardy represented Monaco at the 1963 Eurovision Song Contest in London, singing L’amour s’en va and coming fifth alongside the French entry. That autumn she released her second album, Le Premier Bonheur du Jour. By then she was at the forefront of the “yé-yé” wave (so called to imitate the “yeah yeah” of British and American rock rollers), but although other yé-yé girls such as Sylvie Vartan and Brigitte. Bardot was mostly frivolous, while Françoise Hardy’s music retained its characteristic meditative, melancholic quality.

Desperate for French recording facilities, she began working in London, where she gained a British following. Tous les Garçons reached No. 36 in the British charts in 1964 and All Over the World, her plain English single, made the top 20 and stayed in the charts for 15 weeks, and is perhaps her most famous recording internationally.

Her other albums included Comment te dire adieu (1968), Message personnel (1973) and Clair-obscur (2000), none of which had the same impact on the English world. Her penultimate album, L’amour fou (2012), her half-spoken and half-sung words, was conceived as a philosophical soundtrack to a novel of the same name that she published two years later.

During lulls in her musical career, some of them long, Françoise Hardy found a worthwhile distraction in astrology and spent four years at one time with her most comprehensive books on the subject. She was a Capricorn, which explained her shyness, she said, because “when the sun is in Capricorn you are not there…you are below the horizon, you are invisible”.

Her last album, Personne d’autre, was released in 2018 which contained 10 original songs, including one in English, You’re My Home. Many of her lyrics relate to her many years of development, dealing with lymphatic cancer and facing her own death. “Time’s not speeding up anywhere,” she sang on Un seul geste, and both Train spécial and Le large seemed to say goodbye soon. However, she maintained her air of sleek and elegant Parisian chic.

Her memoir was translated into several languages including English, where it was published as The Despair of Monkeys and Other Trifles (2018), the title coming from the name of the monkey puzzle tree she often visited in the Parc de Bagatelle. Its hard, sharp leaves, she said, reminded her of “men who made me despair”.

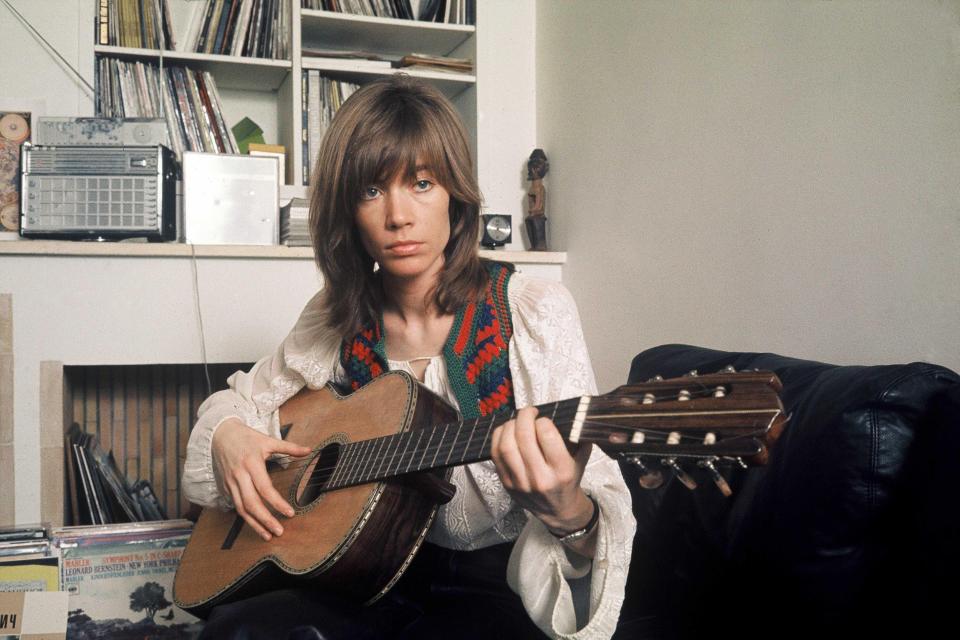

Françoise Hardy’s partner in the 1960s was the photographer Jean-Marie Périer, whose pictures of her unsmiling, her hair falling over her shoulders and her eyes fixed on a distant point, adorn her early record covers.

In 1981 she married Jacques Dutronc, a fellow singer-turned-actor with whom she previously had a son, the jazz guitarist Thomas Dutronc. They lived in a large, split-level apartment close to the Arc de Triomphe, although Dutronc, like her own father, was often absent, spending much of his time on their Corsican retreat, and they formally separated in after that, although they never divorced.

She is survived by Dutronc and her son.

Françoise Hardy, born 17 January 1944, died 11 June 2024