“Are we alone?” It is the age-old question of life in the universe, a question that astronomers and astrologers around the world are trying to answer.

Although Earth is the only planet in our solar system with an abundance of life, astronomers and space agencies are looking in our own backyard for signs that we are not alone. And many believe that the best places to look are the icy moons around two of the largest planets, Jupiter and Saturn.

Currently, there are seven bodies in the outer solar system that are believed to have oceans beneath their crust: two of Saturn’s moons, Titan and Enceladus; three of Jupiter’s moons, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto; one of Neptune’s moons, Triton; and finally, Pluto.

They may have water, but do they have the chemical ingredients to create – and sustain – life?

SEE | Ocean life: The search for life

Recently, a study published in the journal Astrobiology focused on the possibility of life on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon.

The study aimed to answer the question: If something were to hit Titan, creating a melting impact crater, could organisms on the surface make it down to the ocean where they could support life?

The answer, unfortunately, was no.

“ has found that even in the most optimistic scenario we could think of the size of an organism that makes it small enough,” said Catherine Neish, lead author of the study and professor of Earth sciences at Western University.

“It’s so small that either life would be very difficult to sustain over time, or in a slightly more positive case, maybe it’s there, but it’s so low that we need better instruments to level detect very low activity.

“So it’s not the successful biosphere that we expected.”

However, that doesn’t necessarily mean the search for life on other icy moons – or even Titan – is dead in the water.

Shannon MacKenzie, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University, said she believes it was a very good study. However, she notes that there is much about Titan that we do not know.

“Studies like this are very difficult to do, because we don’t know, first of all, what’s on the surface of Titan,” she said. “So you have to make an assumption about what kind of organism is mixing in that impact melt. The lab-based or analog images that we’ve studied well here on Earth, that’s it – they’re analog. They’re the beat it’s our best guess. of what’s sitting on the surface.”

Another issue for astrobiologists is that they don’t know how long Titan’s thick atmosphere carried organics down to the surface.

Other moons, other opportunities to find life

Although Neish is skeptical of subterranean life on icy moons, she is not completely ruling out Titan.

“On Earth, we don’t see life just spread evenly across the ocean: it’s in these microhabitats that could cluster near the ocean floor… It’s not evenly spread. And so I’m hopeful that maybe on Titan, maybe the organisms aren’t evenly distributed throughout the entire ocean, maybe they stay trapped near the ice-ocean interface.”

There is also the possibility that something is happening below the surface, hundreds of kilometers below the ice that could sustain it. She said there is a paper coming out that will discuss that prospect.

And, of course, there are other places in the solar system that are good candidates, including two of the most talked about: Enceladus and Europa.

Missions to the moon

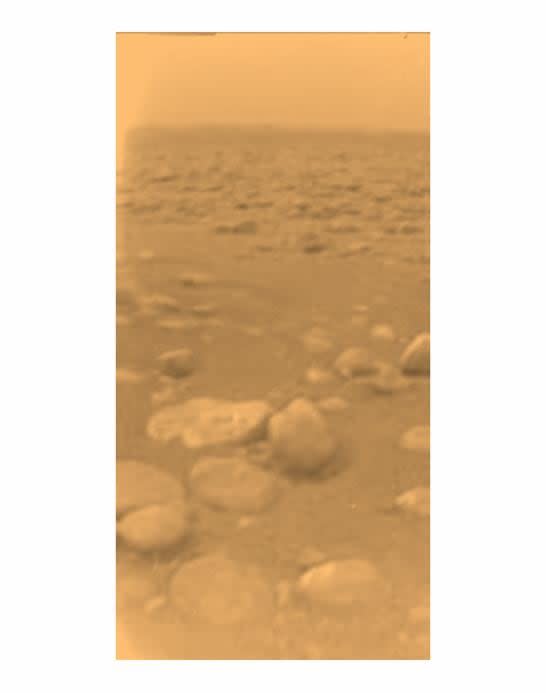

In 2005, the European Space Agency’s Huygens spacecraft (part of the joint NASA-ESA Cassini-Huygens mission) gave us our first glimpse of what lay beneath Titan’s thick, orange-yellow atmosphere — and it was a surprise. As it descended, it caught large lake bodies – later confirmed to be made of hydrocarbons – and, once on the ground, fine pebbles.

That is the only mission to another lunar surface. And while the data collected was extremely valuable, it was limited.

This image was returned on January 14, 2005, by ESA’s Huygens probe during its landing on Titan. The surface with pebble-sized objects is darker than first expected, composed of a mixture of water and hydrocarbon ice. There is also evidence of erosion at the base of these objects, indicating possible fluvial activity. (ESA/NAS/JPL/University of Arizona)

But that is about to change.

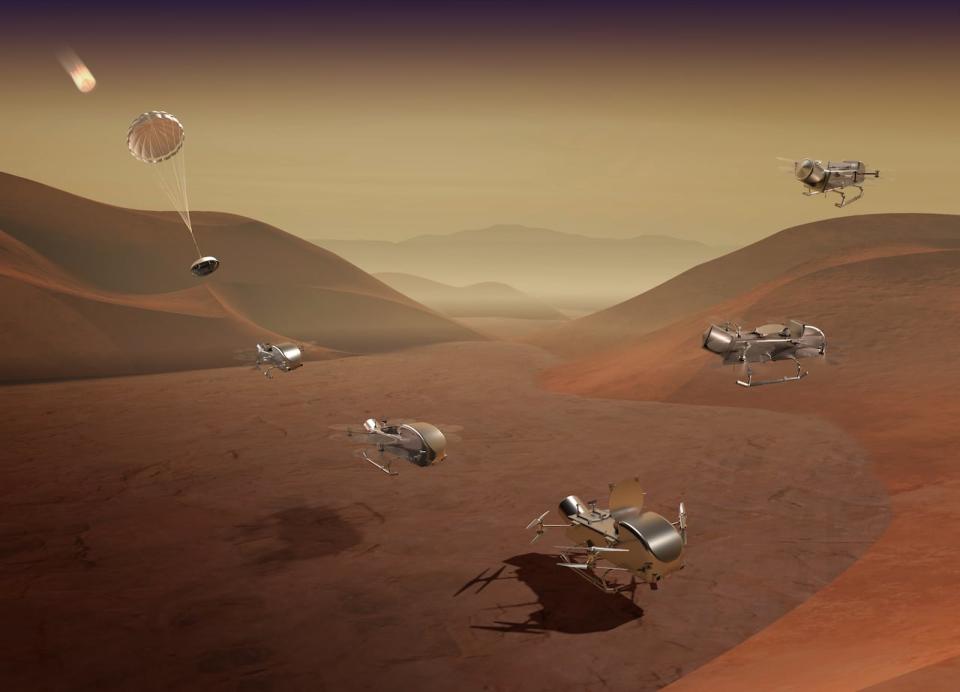

NASA plans to launch a rotorcraft mission – called Dragonfly – that will fly around Titan gathering vital information that will help astronomers and astronomers further study the moon and its composition (Neish is the head of astronomy for Dragonfly, and MacKenzie is also part of the team) .

The two scientists are anxiously awaiting the launch, which has been set for some time in 2028.

“We’re going with Dragonfly to really understand how organic chemistry can evolve in these other environments in the solar system to better understand what happened on our own planet before life appeared in charge and chemistry, rewriting chemical history,” MacKenzie said.

The Dragonfly rotorcraft lander, shown here in an artist’s rendering of the mission concept, will land on Saturn’s moon Titan and then make multiple flights to explore different locations as it determines the habitability of Earth’s ocean environment. (NASA/Johns Hopkins University/Steve Gribben)

And in October the Europa Clipper will be launched to its namesake moon orbiting Jupiter. Along with Saturn’s moon Enceladus, it is considered a worthy place to search for life: it spews particles into space from cracks in its surface ice.

MacKenzie said she is excited about the upcoming mission and, with so many unique moons in our solar system, there are plenty of places to look for life.

“We have these different flavors of sea life available to us, and I think that’s why we need a whole fleet of missions to explore them because they’re different,” she said.