In the United States, wildland firefighters are able to stop about 98% of all wildfires before the fires have burned even 100 acres. That may sound comfortable, but decades of quickly suppressing fires have had unintended consequences.

Fires are a natural part of many landscapes around the world. When forests are not allowed to burn, they become denser, and dead branches, leaves and other biomass accumulate, leaving more fuel for the next fire. This results in more extreme fires that are even more difficult to put out. That’s why land managers set controlled burns and thinned forests to clear the undergrowth.

However, fuel accumulation is not the only consequence of fire prevention.

Fire prevention also disproportionately reduces certain types of fire. In a new study, my colleagues and I show how this effect, known as suppression bias, contributes to the impacts of fuel accumulation and climate change.

What happened to all the low intensity fires?

Most wildfires are low-severity. They light up when conditions are not too dry or too windy, and can often be extinguished quickly.

The 2% of fires that escape suppression are the more extreme fires and much more difficult to fight. They represent approximately 98% of the area burned in a typical year.

In other words, trying to put out all wildfires doesn’t reduce the overall size of the fire equally – instead, it limits low-intensity fires and a large fire still burns. This effect is exacerbated by climate change.

Too much suppression makes fires more intense

In our study, we used fire modeling simulation to investigate the effects of fire suppression bias and see how they compared to the effects of global warming and fuel accumulation alone.

Fuel accumulation and global warming naturally make fires more intense. But over thousands of simulated fires, we found that allowing forests to burn under the worst conditions of more than a century of fuel accumulation or climate change in the 21st century increased fire severity by the same amount.

Suppression also changes the way plants and animals interact with fire.

By removing low intensity fires, humans may be changing the course of evolution. Without exposure to low-severity fires, species can lose traits critical to survival and recovery from such events.

After extreme fires, landscapes have fewer seed sources and less shade. New seedlings have a harder time getting established, and for those that do, the warmer and drier conditions reduce their chances of survival.

In contrast, low-severity fires free up space and resources for new growth, while still maintaining living trees and other biological legacies that support seedlings in their vulnerable early years.

By quickly extinguishing low-severity fires and allowing only large fires, burning conventional fires reduces the opportunities for climate-adapted plants to establish ecosystems and help ecosystems adapt to changes such as global warming. .

Suppression results in a faster increase in the burned area

As the climate gets warmer and drier, more areas are burning in wildfires. Removing fire from prohibition should help slow this increase, right?

In fact, we found that it does just the opposite.

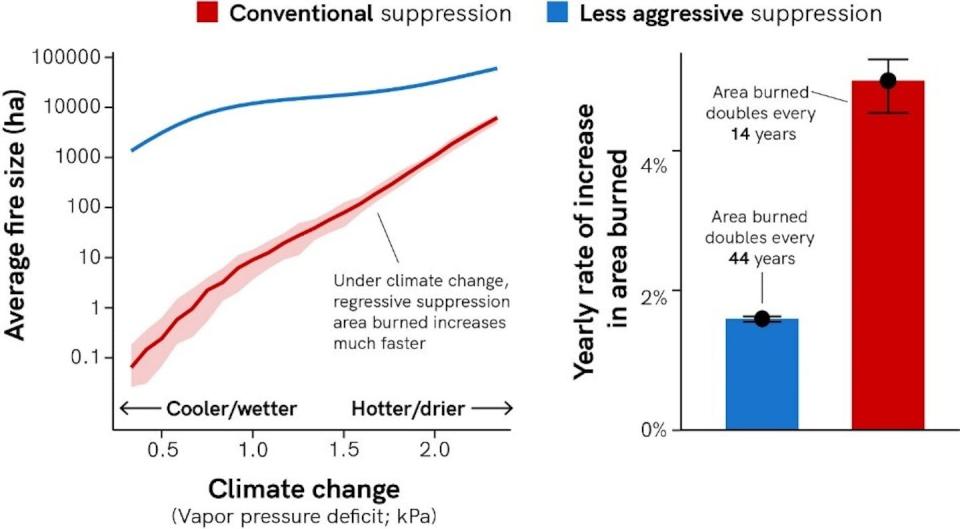

We found that although conventional suppression resulted in less total area burned, the annual area burned increased more than three times faster under conventional suppression than under less aggressive suppression efforts. The amount of area burned doubled every 14 years with normal fire suppression under simulated climate change, instead of every 44 years when low- and moderate-severity fires were allowed to burn. This raises concerns about how quickly people and ecosystems will have to adapt to future extreme fires.

There is no doubt that the amount of area burned is increasing due to climate change. But our study shows that this rate of increase may also be a result of conventional fire management.

Due to the almost complete suppression of fires over the past century, even a small additional fire can create big changes in the more likely future. As climate change continues to fuel more fires, the relative increase in burned area will be much greater.

This puts more stress on communities as they adapt to increased wildfires, from dealing with more wildfire smoke to even changing where people can live.

Way forward

To combat the wildfire crisis, fire managers can be less aggressive in suppressing low- and medium-intensity fires when it is safe to do so. They can also increase the use of prescribed fire and cultural burning to clear brush and other fuel for fires.

These low-intensity fires will not only reduce the risk of large fires in the future, but will also create conditions that favor the establishment of species better suited to the changing climate, helping ecosystems adapt to global warming.

Coexistence with wildfires requires developing technologies and approaches that enable the safe management of wildfires under moderate burning conditions. Our study shows that this may be just as necessary as other interventions, such as reducing the number of fires started unintentionally by human activities and mitigating climate change.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by Mark Kreider, University of Montana

Read more:

Mark Kreider receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the USDA Forest Service.