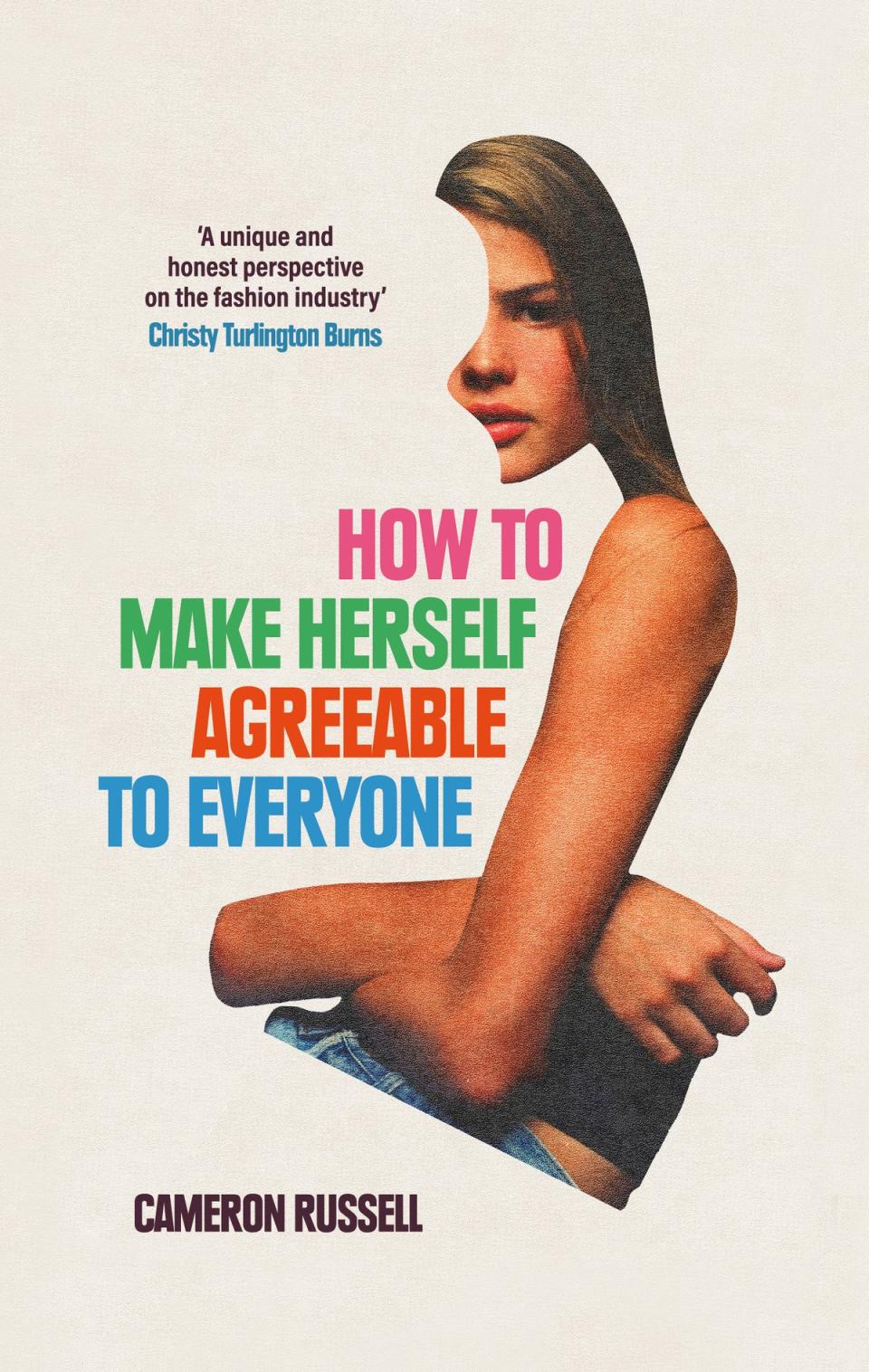

When we talk about Zoom, Cameron Russell is sitting under a slightly surreal statue of dozens of metal birds. It looks like a scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds. ‘I’m in a hotel in LA,’ she says with a laugh. During fashion month, Russell was my companion of sorts. In quick moments I devoured her thoughtful new memoir, How to Make Herself Agree with Everyone. In it, she details the seedy, exploitative sides of the fashion industry: telling you to lose weight, being pumped full of alcohol as a form of sexual assault, constant topless pictures, racism.

Russell, 36, has been modeling since she was 16; She was the face of campaigns for Louis Vuitton, Calvin Klein, a Vogue cover girl and a Victoria’s Secret Angel during the lingerie brand’s runway shows. She was raised in Cambridge Massachusetts, and moved to New York after finishing high school. His first kiss was with a male model. ‘Photographers jailbait me,’ she writes, ‘someone invites me for drinks. Eventually I will find my body in bed next to him. Not me: surprisingly enough I myself will be gone by then.’

But this being Russell, who has a degree in economics and political science, the book also questions the idea of consent, control and the complexities of being involved in an industry so big for good treatment.

Russell went viral in 2013 for her Ted Talk (with more than 40m views), entitled Looks Aren’t Everything, Believe Me, I’m a Model, as well as in 2017 when she shared an avalanche of #MeToo allegations from co-models. about #myjob should not include abuse. She wanted to write the book to examine her history as more than ‘Instagram Captions’ in an ‘attention economy’.

‘Fashion encourages us to treat the industry and ourselves as superficial, unimportant and irreplaceable,’ she says. ‘We are much more than that. But to achieve that we have to take ourselves seriously.’ What fascinates Russell is the shades of gray that are present in any life, no matter where you work or where you are. ‘There is a story about the fashion industry that is widely accepted. But I think so [it] made up of people who are here because first, there was fashion [about] culture, belonging, community and expression. I would say I have worked in fashion for 20 years [that it’s] which are not particularly racist or patriarchal or with particularly appalling labor practices. Like many industries, it can be all of those things. What is exceptional, I think, is that fashion speaks the language of beauty and fantasy and grace. And so there is this expectation with those things.’ Her narration of events is touching. Words and names have been edited in the book. Most of them are obvious: experiences like Victoria’s Secret Angel, allegedly lucky from Gérald Marie, the head of the elite agency hit by rape allegations.

‘We know what we are selling,’ she writes. ‘Isn’t that right? Perhaps the real problem is the out-of-contract exchanges. All the flirting, the casual nudity, the dinners, the texting, all before anyone is paid. It is off the books, uncontrolled. I doubt that many of the girls want to touch these men or show them their tits, at least not for free. But that’s the only way in.’

Why keep the names out? ‘It’s no use having a scapegoat,’ she explains thoughtfully. ‘Our media love to say that there is a victim and this is a villain. It doesn’t leave any room that you can be a victim and you can be comfortable and both of them are not even aware of the full complexity of what’s happening.’

She continues. ‘I don’t want to blame one person. I blame myself and I blame everyone. I blame the culture we are all building together. And I blame the system that does not give us the right not to be understood. How can we change that? That is my main concern, not a person’s name.’

There are common truths and familiarity in his story. But separating the stigma of body image and our appearance is now a free market: with social media, we’re all objectified. ‘At the age of 16 I discovered that I could be commodified, that my body and face could be sold. Now that’s almost universal,’ she says, citing an article about influencers making money off their children (something close to home for Russell: she lives in New York with her husband and two young children, a daughter two-year-old and a five-year-old son, as well as a 13-year-old stepson.)“Their parents probably think this is the most money they’ll make. This is how I could get them a job. This is how my child can be important and valuable in this world. I don’t think people want to harm their children. I think they want to help their children survive.”

But social media has opened up modeling and allowed creators to have agency over their images and platform. ‘There is a lot to criticize about how models are asked to come into the industry, [but] that’s not to say that there aren’t plenty of examples of how you can be in front of the camera and do important and powerful work.’ Russell is certainly a great example of that.

‘How to Make Herself Agree with Everyone’, by Cameron Russell (Oneworld; £18.99), is out now, amazon.co.uk