The pyramids in and around Giza have presented a fascinating puzzle for thousands of years.

How did the ancient Egyptians move limestone blocks, some of which weighed more than a ton, without using wheels? Why do these burial structures appear to have been built in the remote, inhospitable wilderness?

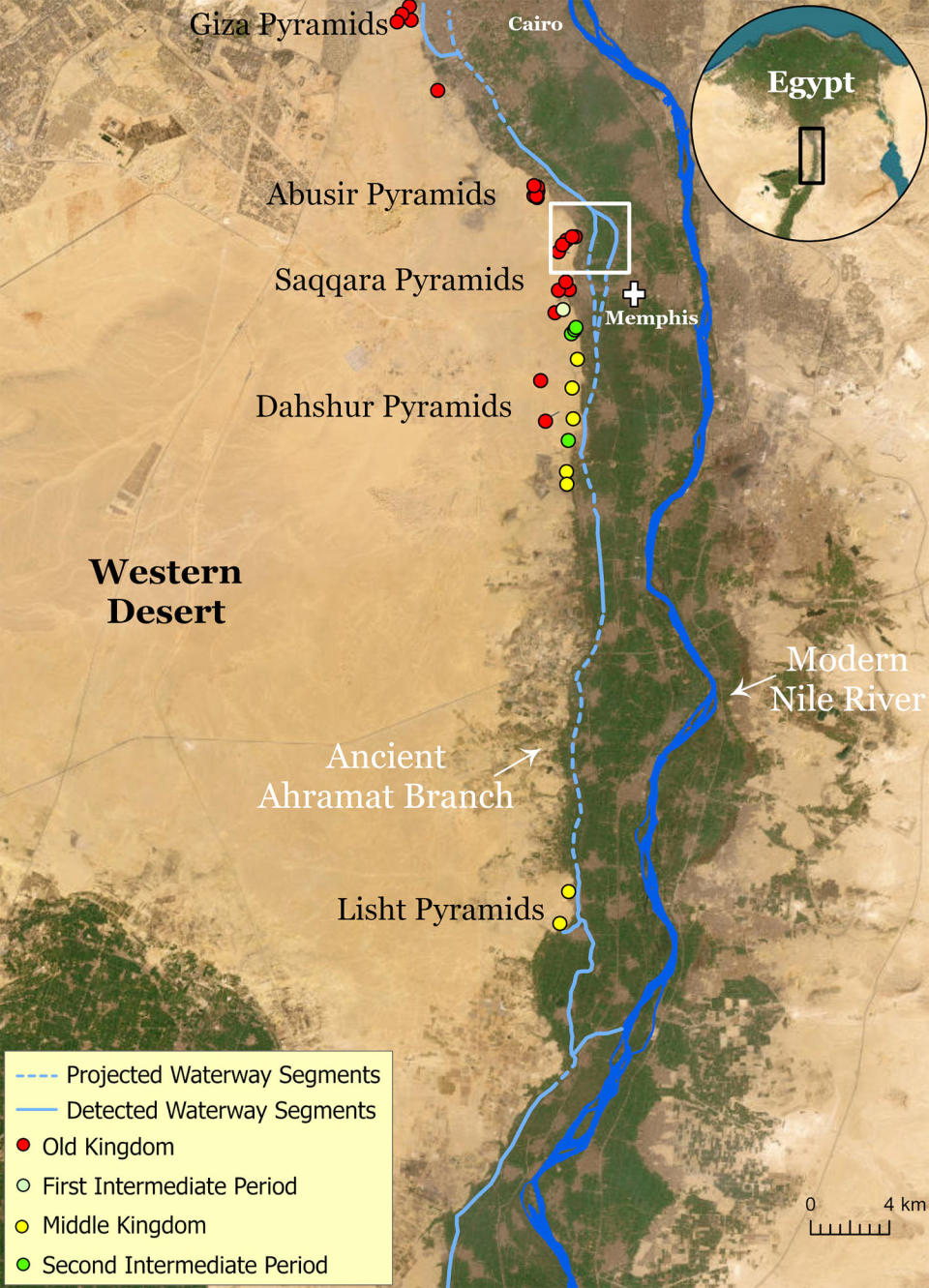

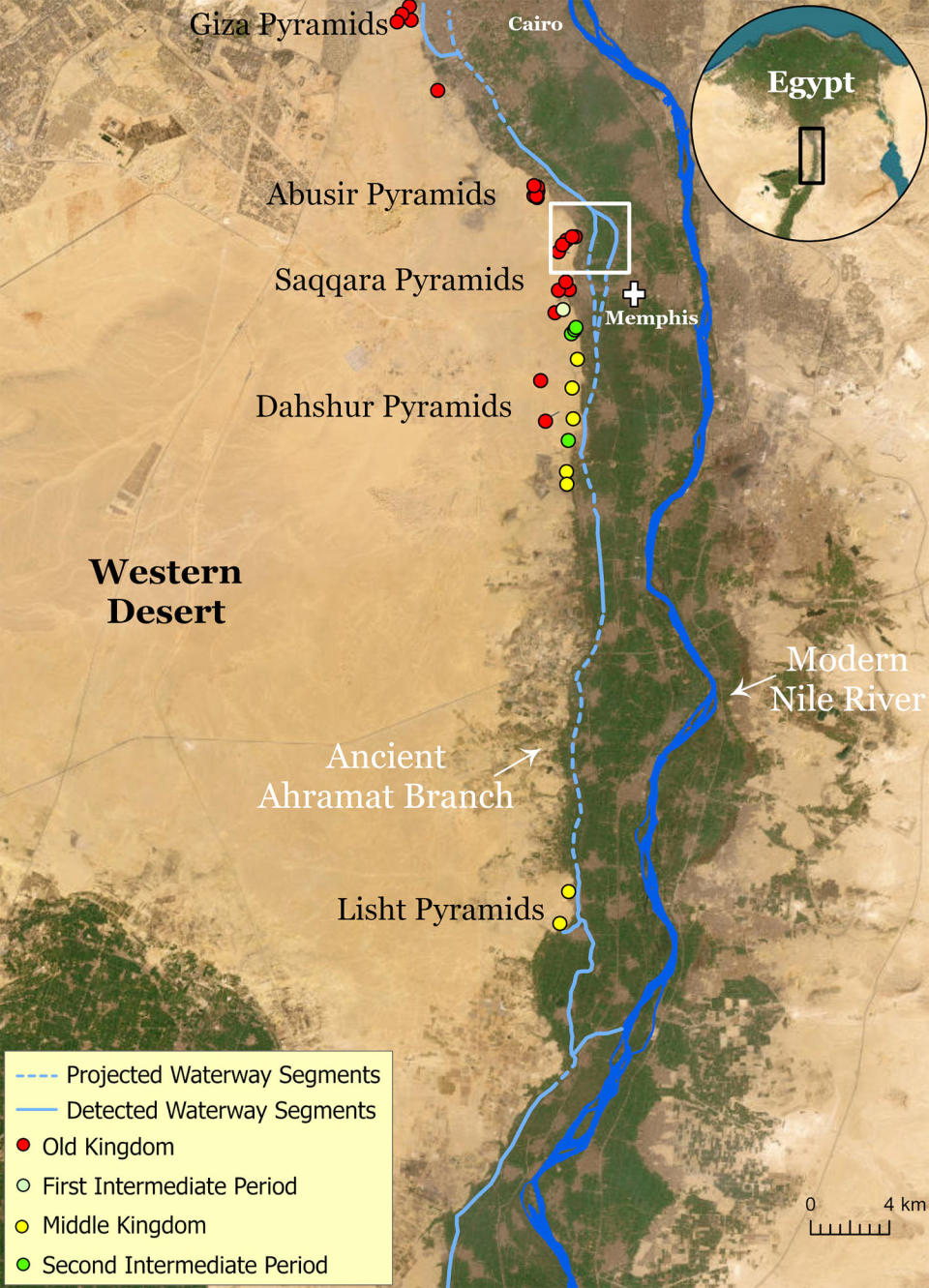

New research – published Thursday in the journal Communications Earth & Environment – offers a possible answer, providing new evidence that a vanished branch of the Nile River once weaved its way through the landscape in a much wetter climate. The many Egyptian pyramids over a 40-mile-long range rimmed the waterway, says the study, including the most famous complex in Giza.

The waterway allowed workers to transport stone and other materials to build the monuments, according to the study. Elevated causeways stretched out horizontally, connecting the pyramids to river ports along the banks of the Nile.

It is likely that the river dried up over time and eventually filled with silt, due to drought combined with seismic activity that tilted the landscape, removing most of its track.

The research team based its conclusions on data from satellites that send radar waves to penetrate the Earth’s surface and detect hidden features. He also relied on cores and sediment maps from 1911 to locate and trace the route of the old waterway. Such tools are helping environmental scientists to map the ancient Nile, now covered with desert sands and agricultural fields.

Experts have suspected for years that boats carried workers and tools to build the pyramids. Some previous research has advanced hypotheses similar to the new study; the new results confirm the theory and map a much wider field.

“The mapping of the ancient Nile channel system is fragmented and fragmented,” the new study’s author, Eman Ghoneim, a professor of earth and ocean sciences at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, wrote in an email. “The ancient Egyptians were using waterways for transportation more often than we thought.”

The study looks at 31 pyramids between Lisht, a village south of Cairo, and Giza. They were built about 1,000 years ago, starting around 4,700 years ago. The pyramid complexes contained tombs for the Egyptian royal family. High officials were often placed nearby.

Some of the granite blocks used to build them were sourced from sites hundreds of miles south of their sites. In some cases, the blocks could be “mammoth,” weighing several tons, said Peter Der Manuelian, professor of Egyptology at Harvard University and director of the Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East.

Manuelian, who was not involved in the new study, said wheels were not used to move the large blocks, which is one reason researchers have long suspected the Egyptians moved materials by water.

“It’s all sledges,” he said. “Water helps a lot.”

In the past, researchers have suggested that the Egyptians may have carved canals to the pyramid sites.

“Canals and waterway systems have been known for many years now,” Manuelian said. But newer theories suggest the Nile was closer to the pyramids than researchers once thought, he said, and new tools can provide some proof.

“Archaeology has become more scientific, and you have excellent radar and satellite imagery,” he said.

He also said that the new study helps to improve the maps of ancient Egypt.

The results suggest that the Egyptian climate was wetter overall millennia ago and the Nile carried a higher volume of water. It split into multiple branches, one of which – which the researchers call the Ahramat Branch – was about 40 miles long.

The locations of the pyramid complexes included in the study correspond in time with estimates of the location of the river’s branch, according to the authors, as water levels rose and flowed over the centuries.

In addition, some pyramid temples and causeways appear to be horizontally aligned with the ancient river bed, suggesting that they were directly connected to the river and were probably used to transport building materials.

The study builds on research from 2022, which used ancient evidence of pollen grains from marsh species to suggest that a waterway once cut through the present-day desert.

Hader Sheisha, the author of that study who is now an associate professor in the department of natural history at the University of Bergen Museum, said the new findings provide much-needed evidence to strengthen and expand the theory.

“The new study, consistent with our study, shows that when the pyramids were built, the landscape was different from the landscape we see today and shows how the ancient Egyptians could interact with their physical world and use their environment to achieve their massive project,” Sheisha said in an email.

Ghoneim and her team explain in the study that the Ahramat Branch moved eastward over time, a process that may have been triggered by a drought around 4,050 years ago. Then it dissolved gradually, only to be covered in silt.

She said they plan to expand their map and work to detect additional buried branches of the Nile floodplain. Determining the outline and shape of the ancient river branch could help researchers find the remains of undiscovered settlements or sites before the areas were opened up.

Manuelian said today, “housing goes almost up to the edge of the Giza plateau. Egypt is a great open-air museum, and there is more to discover.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com