Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on exciting discoveries, scientific advances and more.

In an ancient Mayan temple pyramid in Guatemala, archaeologists recently discovered the scorched bones of at least four adults who were members of the royal dynasty. The burning indicated that their remains were deliberately exhumed and potentially public, according to new research.

The bones provide a rare insight into the deliberate destruction of the body in Maya culture to mark dramatic political changes.

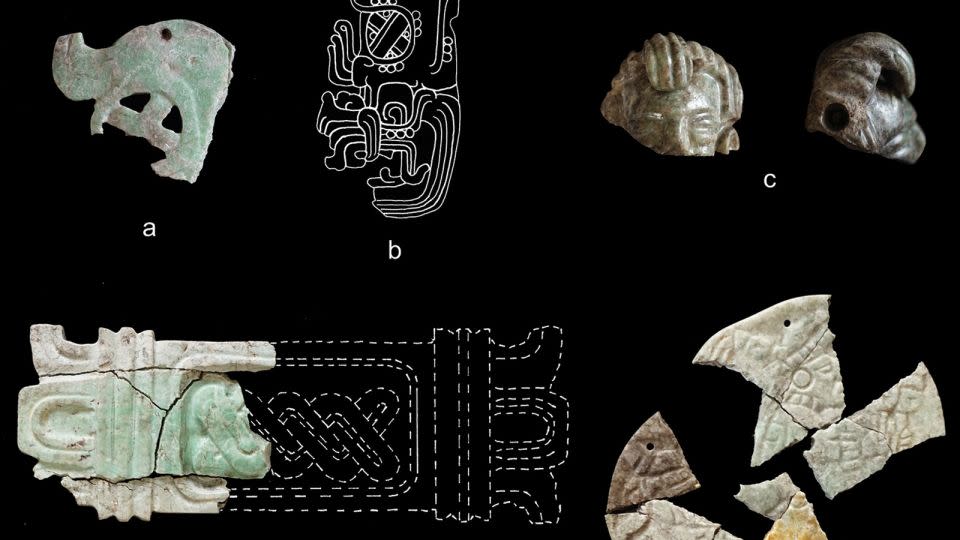

All the remains belonged to adults, and the scientists identified three of them as men. Two were between 21 and 35 years old, and one was between 40 and 60 years old, researchers reported Thursday in the journal Antiquity. Among the bones were thousands of burnt objects — whole and in pieces — including body ornaments made of greenstone (including green minerals, jade), pendants made of mammal teeth, shell beads, mosaics and weapons. Its wealth and abundance indicated the royal status of the people in the tomb.

But it was unusual for royalty to burn artifacts and relics, as was their placement in this pyramid chamber. The revelation shed light on the rise of a new type of leader who likely redefined power during a period of societal transformation, the study’s authors said.

Ritual desecration of bones and royal trappings

Scientists found the burnt bones and grave goods in 2022 at the bottom of the chamber below a temple, under construction material debris. The burial was under about 5 feet (1.5 meters) of large stone blocks typically used for building facades — an unexpected arrangement for people of royal descent, said lead study author Dr. Christina T. Halperin. , associate professor of anthropology at the University of Montreal.

Maya societies usually kept royal relics in accessible spaces where visitors could make offerings. In comparison, this room has no significant signs of what you would normally have for a royal burial,” Halperin said. “They dumped it in this one spot. And then they threw all the construction fill right on top of it.”

Shrinking and warping in the charred, broken bones revealed that they had been burned in a huge inferno at a temperature of more than 1,472 degrees Fahrenheit (800 degrees Celsius). Radiocarbon dating — analyzing the decay rates of carbon isotopes to determine the age of objects — showed that the burning occurred around 773 to 881. However, the analysis also showed that the people died decades earlier; perhaps up to a century before their skeletons burned, suggesting that the fire was related to events that occurred long after their deaths, the scientists wrote.

“This is an amazing hoard of cremated human remains and valuables clearly linked to royalty,” Dr. Stephen Houston, professor of anthropology and history of art and architecture at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, told CNN in an email.

“Halperin is one of our most talented field workers,” said Houston, who studies ancient Maya culture but was not involved in the research. “This article is an example of how we should interpret unusual remains,” he said.

Fire marks the rise of a ‘foreign’ leader

Researchers found the remains in a site called Ucanal, located about 249 miles (400 kilometers) north of Guatemala City. The ancient city was the capital of the Maya kingdom of K’anwitznal, and during the peak of Ucanal, from about 630 to 1000, urban settlements covered about 10 square miles (26 square kilometers).

Around the beginning of the ninth century when the remains were burned, carved Maya records described the deeds of a new ruler called Papmalil. The name did not appear in earlier carvings, “and may have been of foreign origin,” tracing its roots to Maya people from another region, according to the study.

Unlike royalty before him, Papmalil’s official title — “ochk’in kaloomte,” or “Lord of the west” — was associated with military leaders, Halperin said. Also, this historical period was marked by changes in political alliances, the dismantling of outstanding old monuments and the creation of new public buildings. Ceremonial burning of the bones of previous rulers may have signaled the change in leadership, the researchers reported.

The ritual exorcism of royal remains by fire was not unknown in Maya culture. The Maya even had a term for it: “och-i k’ak’ tu-muk-il, ‘the fire went into his tomb,’” the researchers wrote. However, there were no scorch marks in the room where the bones and artefacts were found, suggesting that the burning took place elsewhere.

“He could have burned in his original tomb; it could be burned in a public plaza space,” Halperin said. But wherever the remains lay, a blaze of that scale would never have gone unnoticed.

“It was great that the general public needed to be made aware of it,” she said. After the fire, the placement of the blackened remains in the great temple pyramid would likely have been part of other ceremonies commemorating Papmalil’s rise to power.

Mayan society developing

It’s really exciting to find ancient Maya evidence that points to transformative social change,” said Halperin.

“We know very little about the politics happening during this time, so it’s an important event that helps us identify a political transition. It really emphasizes that yes, political dynasties fell. But there is also a renewal and reworking of society in various areas of the Maya world.”

This enigmatic collection of burnt bones and royal artifacts, dumped in a room and covered with building fill, is “nicely elucidated by ritual connections with practices known from Maya hieroglyphs and the arrival of a foreign ascendant in historical records,” which Houston said. . “A wider excavation at Ucanal may reveal another ripple in this transition of dynasties, perhaps in the form of torched buildings or rapid changes in artifacts.”

The discovery also offers insights into the persistence and continuity of Mayan culture, Halperin added.

“It helps to emphasize the fact that Maya societies did not end when their political systems changed,” she said.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com