They draw you in from afar, bright aesthetic pleasures: pastel tutus, pretty girls. When you’re there, you look closer. You notice the darkness around the edges; you feel about the beaten foot inside the pointe shoe. Degas’ dancers mesmerize for the same reason as ballet itself.

A new exhibition, Discovering Degas, provides ample opportunities to observe the paradoxical beauty of the ballet. Opening next week at the Burrell Collection, in Glasgow, it will feature 23 Degas pieces from the museum’s own collection, as well as 30 works on loan from around the world.

Born to wealthy conservative parents in 1834, Degas discovered his love of opera as a child, and began painting scenes from the ballet in 1870. He would remain spellbound by dancers for the rest of his life. of his life – sculpting in wax and clay afterwards. his sight began to fail. By the time of his death, aged 83, approximately half of Degas’ legacy had been given to ballet.

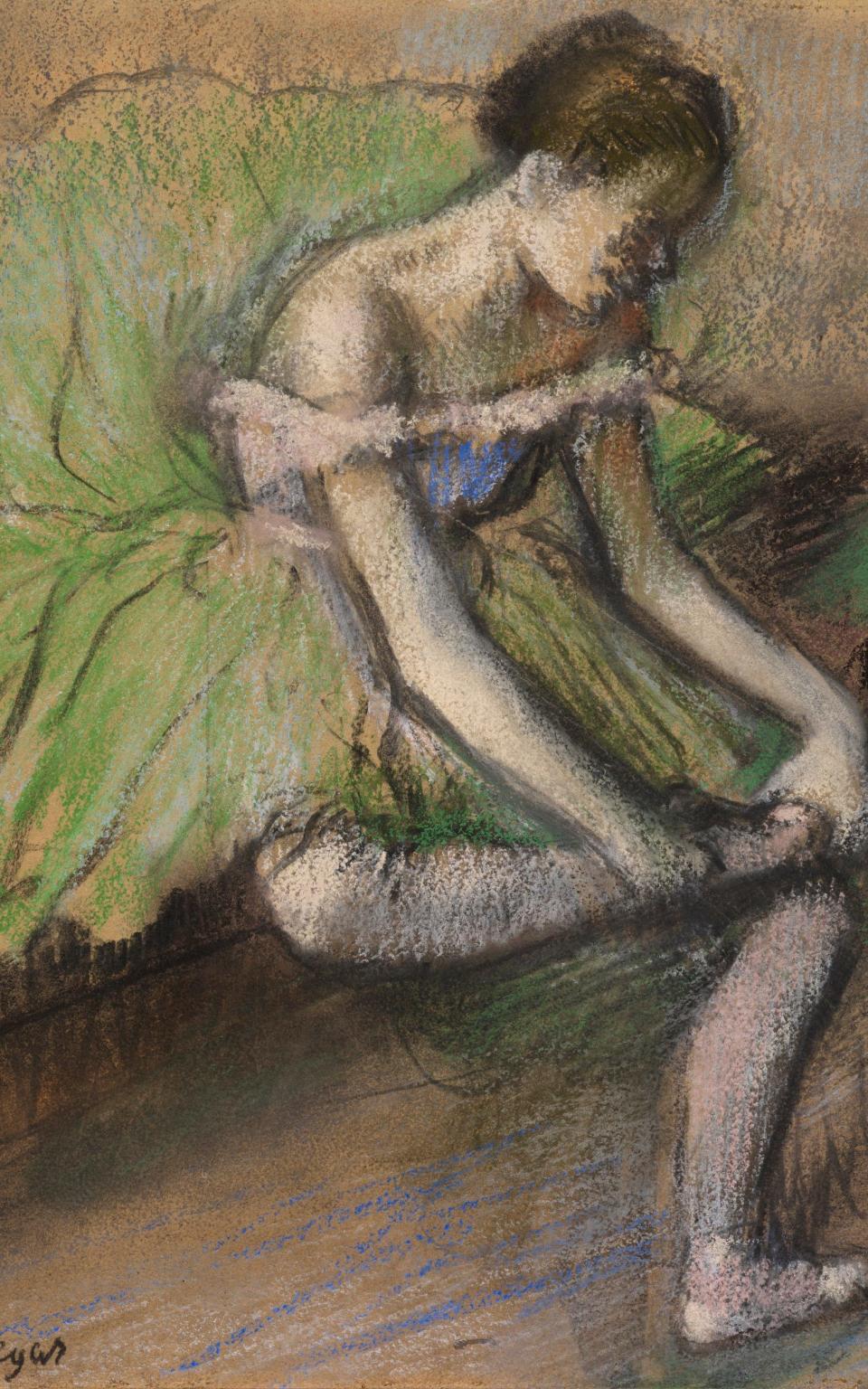

His pictures show the quiet moments in between: a dancer practicing alone on the bar, or putting up the ribbons on her ankles. Degas was less interested in the glamor of the performance than in the dancers’ efforts in the classroom, their backstage preparations and their humdrum waiting in the wings. In paintings such as The Green Ballet Skirt (c 1896), which belongs to Burrell’s permanent collection, a dancer lies on a bench, averting her eyes and massaging her leg. The image shows a fruitful contrast between her beautiful outfit and her tired expression. In A Group of Dancers (c 1898), also exhibited at the Burrell, three women in tutus huddle in a corner of a studio. Bathed in an unearthly emerald light, they lean towards each other, slouching and adjusting their hair.

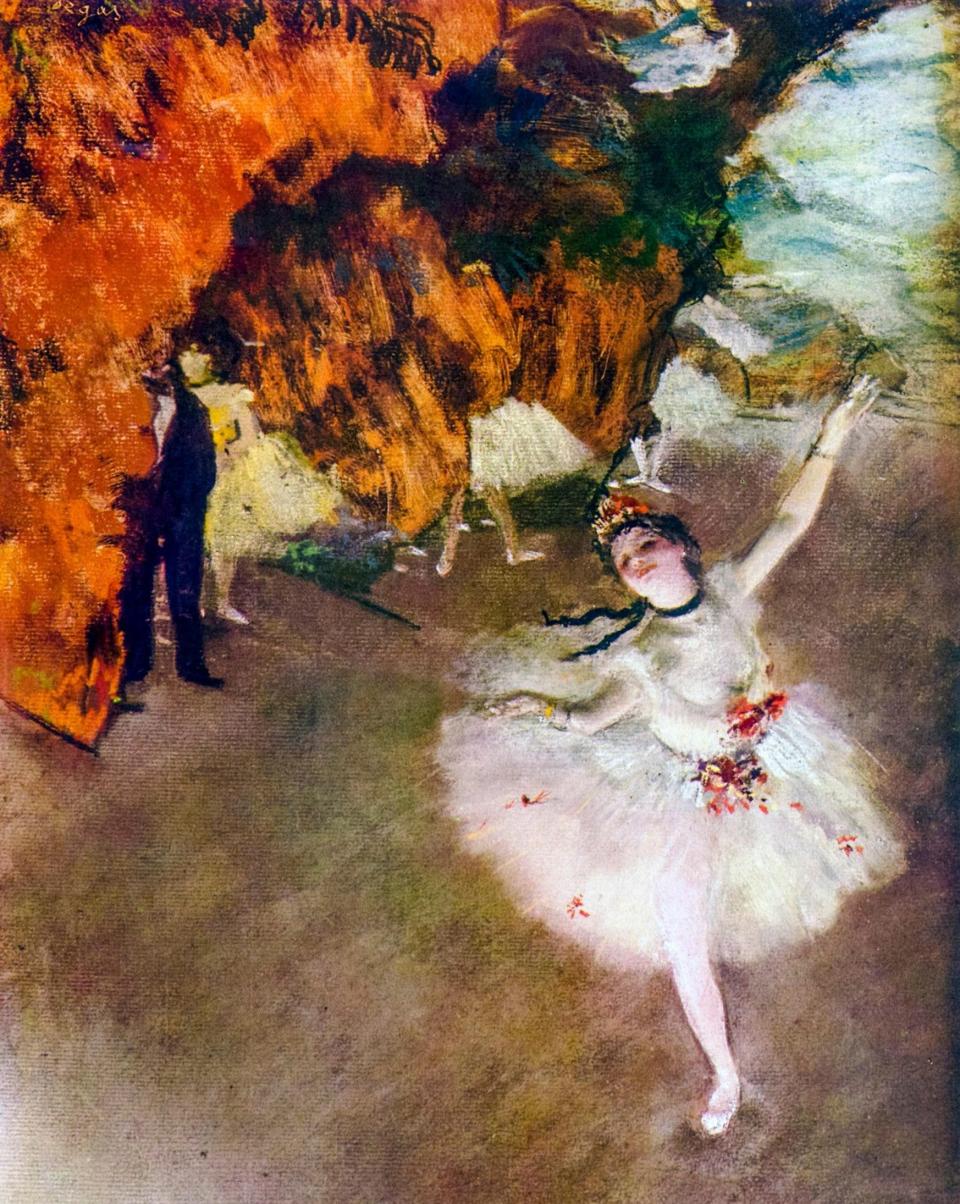

Some of Degas’s paintings show the tender lives of women – some with terrible personalities that lie on the edge. Men in dark suits and top hats skulk in the wings, their faces obscured by shadows. Ballet masters, always men, dominate the classroom, wooden sticks in hand.

In Degas’ era, the Paris Opera was a hotbed of premarital prostitution. Wealthy subscribers – known as abonnements – bought the right to mingle with the dancers backstage and loiter in the wings during live performances. The architecture of the Palais Garnier, opened in 1875, was designed to accommodate encounters between the dancers and their sponsors: the ornate foyer de la danse served as a rehearsal studio and a location for auditions.

“Backstage at the opera was a veritable fiefdom of rich men, who treated the ballet dancers as a kind of game preserve,” the historian Robert Herbert once observed. The three boxes with the best view of the stage were reserved for the emperor, who “did not at all hesitate to use his perch to scout beautiful women”. It was thought that young dancers – trained in seduction as well as ballet – would make excellent mistresses. “Be charming, be wise,” 19th-century ballet master Auguste Vestris told his students. “The box and the orchestra and the seat holders should be eager to take you to bed.”

This system was so intertwined, that it was written up as an attraction in a guide book for the city. “If you are only a financier, an investor wearing yellow gloves, a stockbroker… if you are the uncle of a dancer or her protector… then the portals [to the Opera’s backstage world] be open to you,” wrote Eugène Chapus in Le Sport à Paris.

During Degas, the hemline of the tutu – once a modest, calf-length garment – grew shorter. The Parisian dancers of the 19th century appreciated their artistry less than the sight of exposed legs and arms: a rare occurrence outside the demimonde. Some ballets were full-length entertainments, but more often dancers performed short diversions embedded in the operas. These interludes were usually delayed until Act II – giving the abonnes and their ballerina dates time to finish dinner. (When Richard Wagner overturned this convention, trying to include a ballet in the first act of Tannhäuser (1845), angry members of the Jockey Club voiced their disapproval.)

Degas’ portrayal of the ballet world is cruel. In her paintings, women could only be mothers and dancers; men were authority figures and wealthy patrons, never peers.

The teenage dancers who came to Degas’ studio were often young girls from the Paris Opera Ballet School, known as petits rats – a nickname bestowed by the French poet Théophile Gautier, who wrote of their “activity and destructive tendencies”. Apprentice dancers may be chosen for their looks and talent, and often come from desperate families. Enrollment registers from 1850 show that about half of the students had no known father; the mothers worked as laundresses or concierges for low wages, and welcomed the extra income. Many of the mothers – rather than protecting their daughters – encouraged them to flirt with potential patrons; and in Degas’s paintings, the mothers often appear as dark-clad and menacing as the lecherous male spectators.

But seen from another angle, there is dignity in Degas’ depiction. He sometimes painted étoiles, but more often he hired anonymous students to stand in his studio – elevating them, in his art, to star roles. “Degas seems to have taken great pleasure in drawing attention to the student dancer who is unlikely to have enjoyed it at this date,” write Degas scholars Richard Kendall and Jill Devonyar in Degas and the Ballet: Picturing Movement. In his early ballet works, he sometimes included their names. On an 1880 charcoal sketch of a dancer lifting her leg in batar à la seconde, for example, the teenage model’s name – “Melina” is given as much space as Degas’ own signature.

Just as often, however – and especially in his later work – the women’s faces are obscured. His focus changed from the individual dancers and their identities to the whirlwind of movement and light – tutus swirling, sweaty legs.

Degas may have recognized something familiar in the intense devotion of the dancers. “It is necessary to repeat the same subject, ten times, a hundred times,” said the artist, describing his own approach to the work. Like a Paris Opera trainee endlessly repeating her ploures and tendus, Degas would draw the same model over and over again, in slight variations of the same pose.

And like the dancers, he could be relentlessly vague in his own assessment of his art. He once expressed to a friend that he wished he could buy back all his early work – and destroy it. As I read this story, I thought of Susan Sontag’s 1987 observation that “no species of performance artist is as self-critical as a dancer”. Trained to constantly monitor the mirror for flaws, ballet dancers are notorious perfectionists, never satisfied with a performance.

Sexual exploitation in today’s ballet world is not as obvious as it was in 19th century France; social norms have changed. Companies no longer sell access to dancers’ dressing rooms and do not allow men to roam backstage during performances. The classroom dynamics have also changed. Boarding at London’s Royal Ballet School costs more than £30,000 a year, and the salary of dancers is relatively low; ballet tends to attract children from wealthy families.

Ballet is a popular art form today – but ballet is still a sex symbol. Many dancers supplement their income by moonlighting as Instagram influencers or models. When I was studying ballet in the mid-2000s, I was told that, in crosé devant, I should tilt my head as if to “ask for a kiss”.

Costumes are more revealing than ever; in the mid-20th century, George Balanchine’s costume designer Karinska invented a tutu so short it was almost vertical, revealing the dancer’s entire lower body. Then Balanchine went all out with tutus, putting women on stage in only a thin leotard. Even removing a layer of tulle from dancers exacerbated the pressure to maintain a perfect body.

Although infrequent abuse may no longer be reported in guidebooks, it is now more discreet, and a code of silence prevails. Female dancers are trained to fulfill a choreographer’s vision, shunning their own anxieties for the sake of fitting in. As in 19th century France, tolerance can be rewarded.

Even with the professionalization of ballet, power imbalances still exist. The majority of ballet students and choir dancers are still girls and women, and men are overrepresented in positions of authority. As of the 2020-21 season, men choreographed 69 percent of the ballets registered by major American companies.

Competition for jobs is fierce, especially among women – and few are willing to risk scandal. It is mostly whistleblowers and ex-dancers who dare to go public with allegations of abuse. In 2013, former Russian dancer Anastasia Volochkova compared the Bolshoi to a “huge brothel”, alleging that ballerinas were pressured to sleep with wealthy patrons – claims dismissed by the company’s general director as “ravings”. In her 2021 memoir Swan Dive, the soon-to-be-retired New York Ballet soloist Georgina Pazcoguin alleged that a male colleague, Amar Ramasar, regularly tweaked her nipples in class. (Ramasar denied the allegation.)

Dancers love Degas’ paintings: from students who hang prints of The Dance Class (1874) on their bedroom walls to stars such as Misty Copeland, who recreated Degas’ The Star (1878) for Harper’s Bazaar. Perhaps they see something familiar about the danger on the sidelines and the hard-working faces of the girls – a sisterhood that crosses the ages.

Discovering Degas is at the Burrell Collection, Glasgow, from Friday until September 30 (burrellcollection.com); It is the latest book by Alice Robb Don’t Think, My Friend: On Love and Leaving Ballet (Oneworld, £10.99)