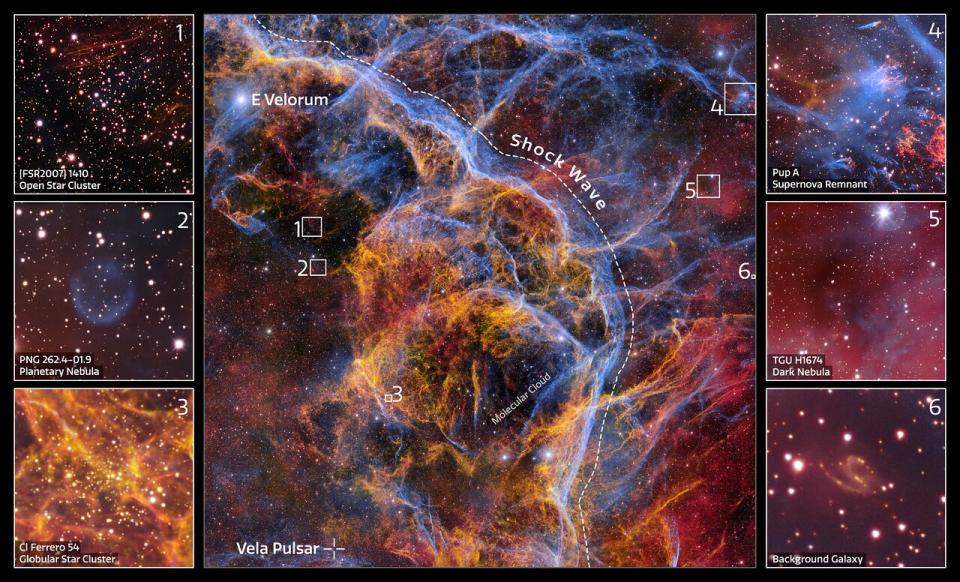

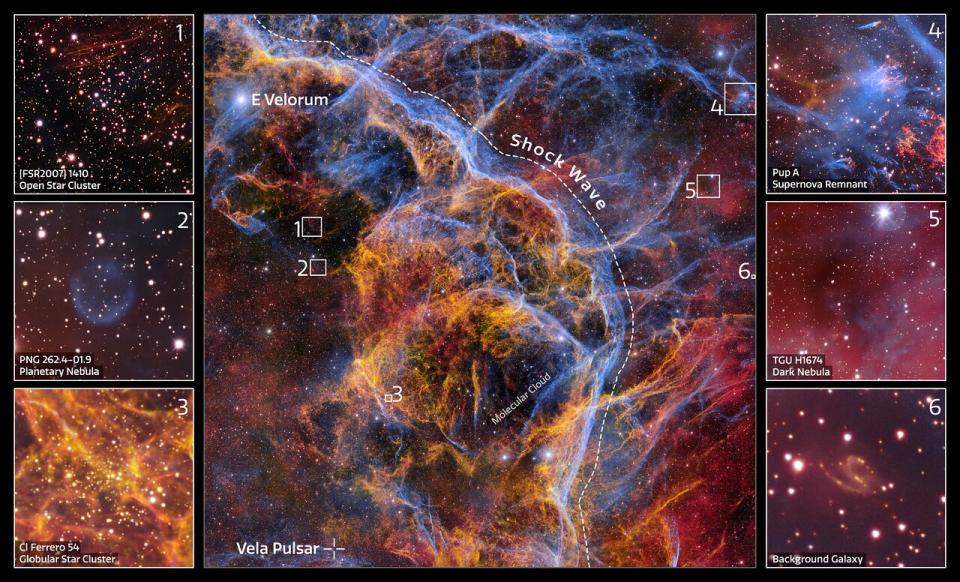

This billowing mass of filaments of dust and tendrils of gas stretched over 100 light year of space like the delicate lace of the Vela supernova remnant – scattered ashes of a star that exploded about 11,000 years ago.

The image was obtained by the Dark Energy Camera (DECam), located on the Victor M. Blanco 4 Meter Telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. DECam was originally designed for remote sensing galaxies to the strength of dark energy while accelerating the expansion of the universe and pulling those galaxies away from us. On completion of that survey, however, DECam was used more generally. It is one of the most powerful wide-field instruments ever built, and this image of the supernova remnant Vela is proof of its capabilities. In fact it is the largest image ever released by the camera at 1.3 gigapixel (1.3 billion pixels) in size. For comparison, a top-of-the-line smartphone might have a 48 megapixel (48 million pixels) camera.

Related: Pulsar surprises astronomers with record-breaking gamma rays

The image has to be large to capture all that detail over such a wide range of horizon. As mentioned, it is a remnant of the supernova Vela a nebula that is about 100 light years across. Being about 800 light-years away, it means that the supernova remnant Vela covers an area of the celestial sphere 20 times the angular diameter of totality moon (which is 31 minutes of arc, or half a degree across the sky).

The Vela supernova museum itself is of vital astronomical importance. It gives us a good insight into the late stages in the development of such a remnant, and gives insight into how material blown out by the supernova gradually disperses into the interstellar medium, which is the thin gas mist that fills. the space between the stars. The shock wave from the ancient stellar explosion that was the supernova remnant of Vela is still expanding into space, where it is colliding with the interstellar medium and compressing it, creating the delicate filaments we see in the image. Absorption lines from elements such as calcium, carbon, copper, germanium, krypton, magnesium, nickel, oxygen and silicon—many of them ionized and doubly ionized—were also detected in the supernova debris. These are heavy features created by fusion processes within the star before it exploded, or by the energy surge released by the explosion itself.

A supernova doesn’t just throw the guts of a star into deep space; it also leaves behind the core of the dead star, which is now compressed by gravity into an ultra-dense object just 10 or 12 kilometers (about 6 to 8 miles) across. It is called a neutron star.

Such an object is usually born spinning many times per second, flashing radio beams from its poles like a cosmic lighthouse. We call things like this “pulsars,” and indeed one lies at the heart of the supernova remnant Vela that radio telescopes have been spinning steadily at a meridian rate of 11 rotations per second.

The Vela pulsar is one of the closest pulsars to us, and it is blowing off what is called a “pulsar wind”, a smaller nebula inside the larger supernova remnant made up of charged particles originating from the pulsar and which influences circumstantial matter dismissed by the person. star as well as the wider interstellar medium. In a way, the remnant and the pulsar wind nebula are like a nebula within a nebula, a-la a cosmic Matryoshka doll. Being composed of energetic particles, a pulsar wind nebula tends to be more detectable in X-rays and gamma rays.

Related Stories:

— Astrophotographers capture the remains of the Vela supernova in exquisite detail

— 3.3 billion Milky Way objects revealed by a massive astronomical survey

— Dark Energy Camera peels back layers of a ‘galactic onion’ stretched across space

Even the constellation that contains the supernova remnant Vela has an interesting history. The constellation Vela is the Sails, but this area of the sky was once part of a much larger constellation called Argo Navis, which was the name of the Greek mythological ship that Jason and the Argives brought in search of the Golden Fleece. This southern constellation was so large that it was incomprehensible, so in 1755 the French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille divided the Argo Navis into three smaller constellations: Carina the Keel, Puppis the Poop Deck (or constellation) and Vela, the Willows.

Those three constellations still exist to this day, but looking at the DECam image, perhaps the Argonauts – we astronomers – may have finally found our Golden Fleece in the shape of the Vela Supernova Remnant.