Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on exciting discoveries, scientific advances and more.

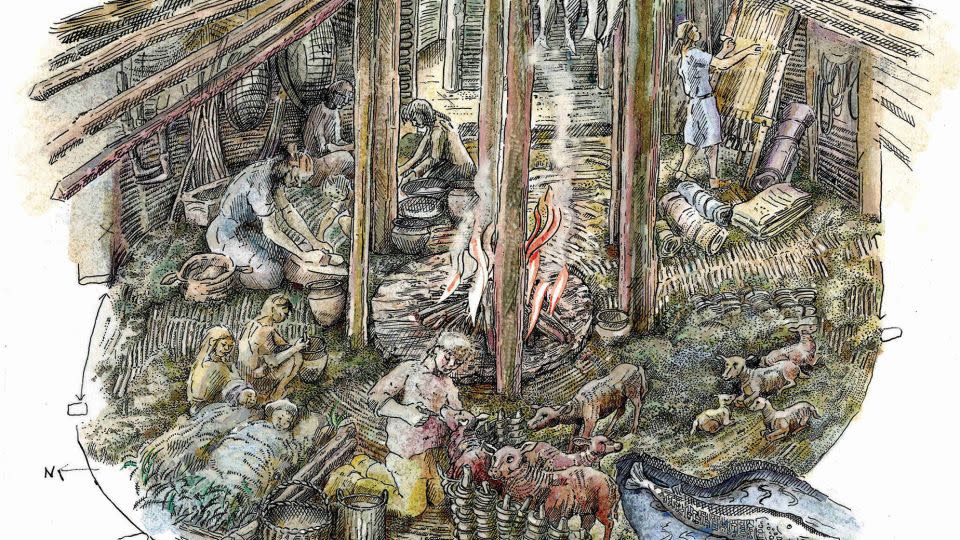

It is late summer 2,850 years ago. A fire breaks out in a stilt village perched above a soft, gentle river that meanders through the moors of eastern England. The tightly packed round houses, built of wood, straw, turf and clay just nine months before, go up in flames.

The inhabitants flee, leaving behind all their belongings, including a wooden spoon in a bowl of half-eaten porridge. There is no time to rescue the fat lambs, who are trapped and burned alive.

The scene, captured by archaeologists, is a vivid and poignant picture of a once-thriving community in late Bronze Age Britain called Must Farm, near what is now the town of Peterborough. The research team published a two-volume monograph on Wednesday that describes their intensive $1.4 million (£1.1 million) excavation and analysis of the site in Cambridgeshire.

Described by the experts involved as “archaeological nirvana,” the site is the only one in Britain that lives up to the “Pompeii premise,” they say, referring to the city frozen forever in time of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 that he has received unprecedented information about ancient Rome.

“In a typical Bronze Age site, if you have a house, you’ve probably got a dozen post holes in the ground and they’re just dark shadows of where it once was. If you’re lucky, you’ll find a few shards of pottery, maybe a hole with a bunch of animal bones. This was the complete opposite of that process. It was incredible,” said Chris Wakefield, an archaeologist with the Cambridge Archaeological Unit at the University of Cambridge, an archaeologist and member of the 55-person team that excavated the site in 2016.

“All the ax marks were used to shape and sculpt the wood. All of those looked fresh, like someone could have done last week,” Wakefield added.

The excellent state of preservation of the site and its contents enabled the team to draw comprehensive new insights into Bronze Age society — findings that could overturn current understandings of everyday life in Wales. ninth century BC

I need a Farm – and Mystery

The site, which dates back to eight centuries before the Romans came to Britain, revealed four round houses and a square entrance structure, which stood about 6.5 feet (2 meters) above the river bed and was surrounded by fence 6.5 feet (2 meters) of. aggravated jobs.

The archaeologists believe that the settlement was twice as large. However, quarrying in the 20th century destroyed any other remains.

Although gutted by the fire, the remaining buildings and their contents were remarkably well preserved by the oxygen-starved conditions of the fens, or bogs, and included many wooden and textile items that were not rarely survives in the archaeological record. Together, traces of the settlement paint a picture of a cozy homestead and relative strength.

The researchers found 128 ceramic artefacts – jars, bowls, cups and cookware – and were able to determine that 64 pots were in use at the time of the fire. The team found several neatly nested storage pots. Textiles found at the site had a soft velvety feel made from linen linen with neat seams and hems, although individual pieces of clothing could not be identified.

Among the wooden artifacts were boxes and bowls carved from willow, alder and maple, 40 shuttlecocks, many with threads still attached, various tools, and 15 wooden buckets.

“One of those buckets … on the bottom of it was loads and loads of cutting marks so we know that there were people living in the kitchen in that Bronze Age when they needed a cutting board right away , flipping that bucket upside down and using that as a cut. surface,” Wakefield said.

“It’s those little moments that come together to give a richer and fuller picture of what was going on.”

The circumstances of the event that ended it are still a mystery. The researchers believe that the fire happened in late summer or early autumn as the skeletal remains of the lambs kept by one family showed that the animals, usually born in the spring, were between three and six months old age.

However, it is still unclear what caused the catastrophic fire. The fire may have been accidental or started deliberately. The researchers uncovered spearheads with shafts over 10 feet (3 meters) long at the site, and many experts think warfare was common during the time period. The team worked with a forensic fire investigator but ultimately failed to identify a specific “smoking gun” clue that pointed to the cause.

“An archaeological site is very much like a jigsaw puzzle. At a typical site you have 10 or 20 pieces out of 500,” Wakefield said. “We had 250 or 300 pieces here and we still couldn’t get the full picture of how this big fire started.”

Continuing thoughts about Bronze Age society

The content in the four preserved houses was “extremely consistent.” Each had a tool kit that included sickles, axes, gouges and handheld razors used to cut hair or cloth. With nearly 538 square feet (50 square meters) of floor space at the largest, each of the dwellings seemed to have distinct zones of activity comparable to rooms in a modern house.

Not all items were of practical use, for example 49 glass beads and others made of amber. Archaeologists also found a woman’s skull, which had been removed from contact, which could be a memorial to someone we had lost. Some of the items found by the researchers will be on display starting on April 27 in an exhibition entitled “Introducing Must Farm, a Bronze Age Settlement” at the Peterborough Museum and Art Gallery.

Laboratory analysis of biological remains revealed the types of food that the community once ate. A pottery bowl with finger marks held his last meal maker – wheat grain porridge mixed with animal fat. Chemical analysis of the bowls and jars showed traces of honey as well as deer, suggesting that the people who used the dishes may have enjoyed venison with a glass of honey.

Ancient excrement found in waste heaps below where the houses would have stood revealed that the community kept dogs that ate scraps from their owners’ meals. And fossilized human poop, or coprolites, showed that at least some inhabitants suffered from intestinal worms.

The waste piles, or midges, were one line of evidence showing how long the site had been occupied, with a thin layer of rubbish suggesting the settlement was built nine months to a year before it went up in flames. Two other factors supported that line of reasoning, Wakefield said.

“The second was that a lot of the wood used in the construction was unseasoned, it was really green, it wasn’t in place long,” he said.

“The third is that we lack the kind of insects and animals associated with human habitation. A worm would soon have beetles (in) … but there is no evidence of that in any of the 18,000 plus logs.”

Because the site, whose content is rich and varied, was only in use for a year, it affected the team’s preconceived “visions of daily life” in the ninth century BC. according to the 1,608-page report.

“We are seeing here not a lifetime’s accumulation, but a year’s worth of materials,” the authors noted in the report. “It suggests that artefacts such as bronze tools and glass beads were more common than we often imagine and that their availability may not have been really restricted.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com