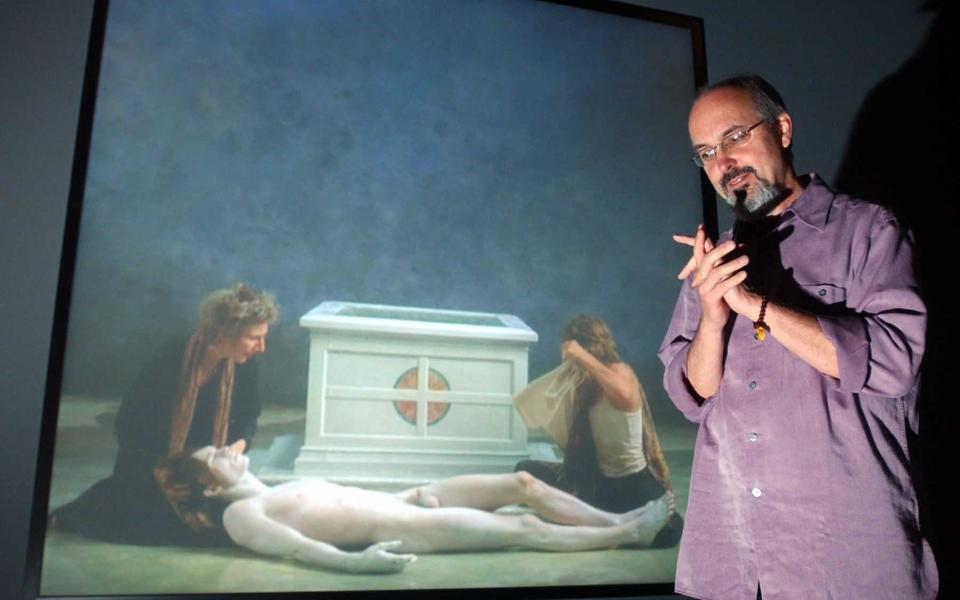

Bill Viola, who has died at 73, was a pioneer in video art, creating technically sophisticated productions that divided art critics, museum curators and the public alike; his videos can be seen in Tate Modern and St Paul’s Cathedral, and were used as the backdrop for Peter Sellars’ 2005 staging of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde.

Described on the one hand as a “Rembrandt for the visual age” and on the other as having a reputation of being “too, too, too early”), Viola focused on life, death and coming to the advancement of consciousness. Many people approached his video art with cynicism, but in 1994 Richard Dorment wrote approvingly in The Daily Telegraph’s Nantes Triptych of Viola: “As the video developed, I gradually began to look at the triptych as a very sophisticated objet d’art, to consider it in purely formal terms, just as I would any other painting or sculpture.”

But HM Revenue & Customs was suspicious, and in 2008 his art was classified as “electrical devices” and therefore subject to the full rate of VAT, then 15 per cent. Haunch of Venison gallery in London took up the cause and HMRC relented, reducing VAT to the 5 per cent rate for sculpture.

In 1996 Viola shot to fame with a larger-than-life video at Durham Cathedral showing a naked man in a swimming pool with his genitalia exposed. “We were advised that it was not sensible for people to see it as they walked in,” explained the Dean of Durham, the Reverend John Arnold.

Viola remained a paradoxical figure. While working in the most modern media – many saw him as the first true master – his interests ranged from the mystical philosophies of the ancient East to the devotional painting of 15th and 16th century Europe. In 2019 the Royal Academy paired his work with drawings by Michelangelo, although that show was criticized as “preachy [and] pompous” by another Telegraph critic.

Having come of age with video development, Viola was constantly experimenting with new technology. The advent of high-definition video opened up even more possibilities, including The Passions, a series of video installations inspired by late Medieval and late Renaissance art that was seen at the National Gallery in London in 2003. This time it was not so Well done Dorment, describing them in the Telegraph as “New Age twaddle, whipped up by digital wizardry to make them look serious”.

William Viola was born in the Flushing area of Queens, New York, on January 25, 1951, one of three children of a Pan Am flight attendant. His mother was an English émigré from Barrow-in-Furness and he filmed a floor-to-ceiling video screen that was part of his Nantes Triptych (1993), now in Tate Modern. On the second screen a man goes into the depths of the water, and on the third a woman Viola is seen screaming as she holds her son.

At the age of six he had a near-drowning experience after falling into a lake on a family holiday. His uncle rescued him, but he recalled that he was not afraid at all. “In fact, it was the most incredible feeling, madness. Like the biggest thing I’ve ever been, almost a moment of paradise that I’ve had all my life,” he said. He drew on the experience in The Reflecting Pool (1977), a series of five videos set in and around water.

As an only child Viola pleaded ill when friends called to play. “I would stay at home and make up these imaginary worlds and planets,” he said. “Later, the beauty of discovering that there was a small electronic camera was that I could take pictures by myself, anywhere.” He was drawn to the counterculture movement, experimenting with drugs, participating in political demonstrations and playing experimental music: “If my parents liked something, I hated it.”

He graduated from Syracuse University, New York, and worked at an early video art studio in Italy and had his first major exhibition in Florence. Back in the United States he was artist-in-residence at the WNET Thirteen Television Lab, New York, and in 1976 created He Weeps for You, a live camera that magnifies a drop of water, for the student union at Syracuse University. It was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, sparking a debate about what constitutes art.

Like many of her contemporaries Viola looked to other cultures, traveling widely, absorbing ancient ways of thinking and recording traditional music, rituals and dance. He visited Java for gamelan drumming, the Himalayas for Buddhist monasteries and Fiji for fire dancing. During that time he kept extensive notes that were a reference for his future work, “like a recipe book”.

In 1995 he represented the US at the Venice Biennale; two years later the Whitney Museum of American Art selected him for a major retrospective, the first held by any museum for a visual artist; and in 2000 his video accompanied a performance of Edgard Varèse’s electronic music piece, Deserts in Fire Crossing Water, at the Barbican Center in London, one of many collaborations with musicians.

His work has also been exhibited at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, and he produced two large screen works for St Paul’s Cathedral: Martyrs (2014), in which four individuals remain battered by the elements, and Mary (2016), depicting the mother of Christ at different stages of their lives.

Viola, quietly spoken, bearded and bearded, met Kira Perov when she organized an exhibition of his work at La Trobe University, Melbourne, in 1977. She followed him to New York and they married in 1980, at a few years arrangement. later in a quiet suburban street in California. He is survived by her and their two sons.

Bill Viola, born 25 January 1951, died 12 July 2024