Farewell to the King. Barry John, the former Wales and Wales Lions winger who was regarded as Rugby Union’s first superstar and was doomed to quit because of the courtesies of a young woman, has died aged 79.

John’s international career lasted just six years, between 1966 and 1972, but nevertheless his brilliance on the pitch led to him being named in the same breath as greats such as Gareth Edwards and JPR Williams. His death, which follows that of his iconic colleague Williams earlier this year, was confirmed in a statement from John’s family on Sunday.

“Barry John died peacefully today at the University Hospital of Wales surrounded by his wife and four children,” it read. “He was a loving dad [Grandad] to 11 grandchildren and a much loved brother.”

Born in Cefnethin, Carmarthenshire in 1945, John represented his hometown club before spells at Llanelli and Cardiff. He would also succeed on the biggest stage. Wales won three Five Nations titles, a Grand Slam and two Triple Crowns during John’s time wearing the No.

It was on that tour, his second after tackling South Africa in 1968, that New Zealand journalists dubbed him John “The King”. However, the gliding, gorgeous playwright would retire the following year, aged just 27. He announced his decision in the Sunday Mirror, explaining that the Warriors’ claustrophobia had become too serious and absurd. Clearly some members of the public considered him to be close to real life royalty.

“I was rugby’s first pop star, superstar, take what you will,” John recalled in an interview with Wales Online. “I came third in BBC Sports Personality, and a month later I was the first rugby player to be the subject of This is Your Life. I was coming off the field against England at Twickenham and Eamonn Andrews is with his big red book.

“I didn’t want to retire, but those were the circumstances. People didn’t understand how you had to go to work, how you had to be fit for rugby at international level. I was becoming lethargic, tired. You can’t be like that on the international stage, especially at No 10.

“The invitations flew thick and fast. I had no time for myself, I knew I wasn’t as sharp mentally or physically as I wanted to be. I was up there [in north Wales] promoting the bank. There were young people outside, many people to greet me. I said a few words, and as I was introducing myself to someone, she curtsied. Not a big one, a little one, but curtsy nonetheless.

“He convinced me that this was not normal. I was becoming more and more isolated from real people. I didn’t need this anymore.”

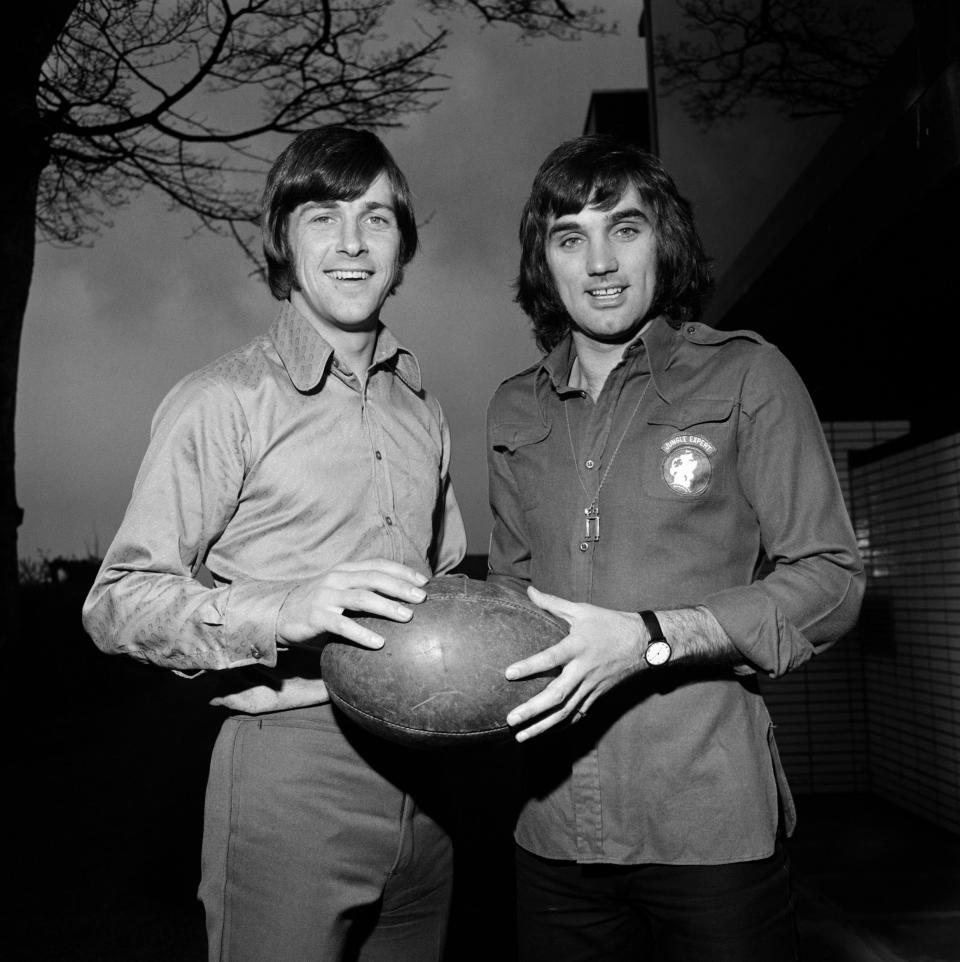

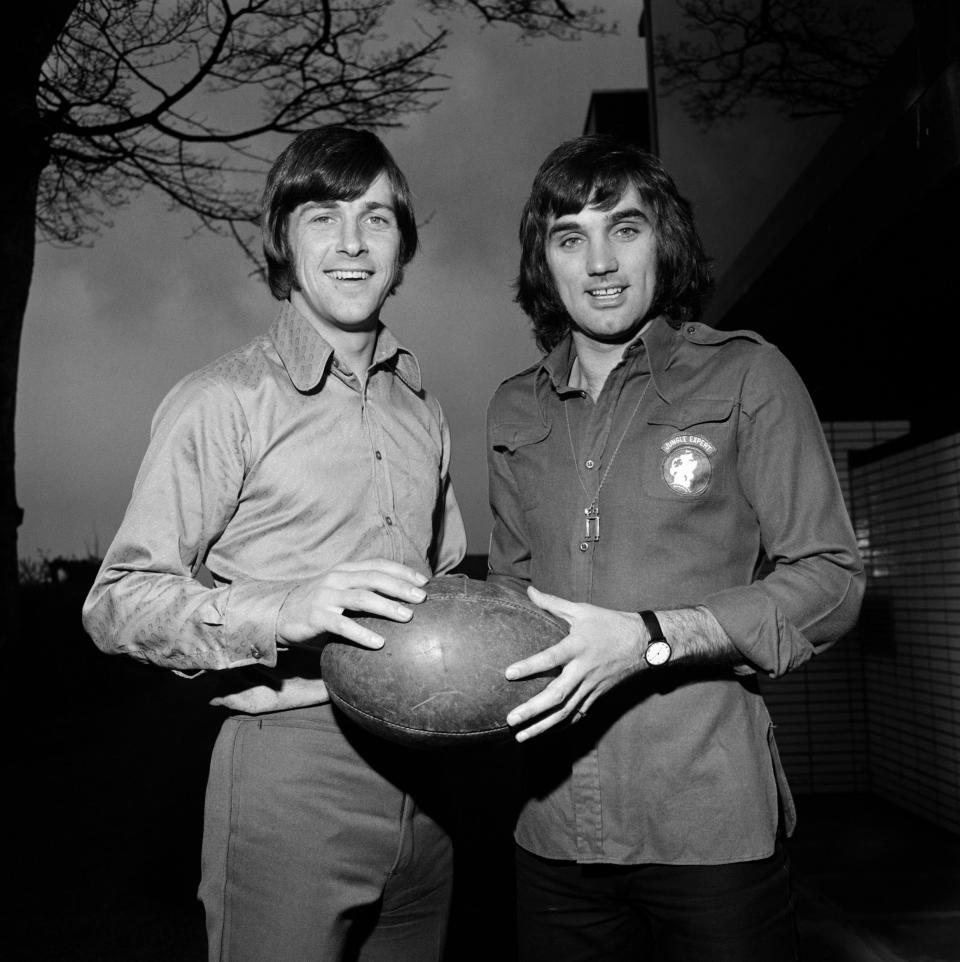

The two figures who beat John to third place in the 1971 BBC Sports Personality of the Year competition were Princess Anne and George Best. John got to know Best and considered the Manchester United forward a friend. In fact, he would interview Best for his own TV show a few years later.

There is no doubt about the rich legacy that Sean has left. Edwards, a half-back partner for Wales and the Lions, wrote in his autobiography of John’s determined spirit on the field. He seemed to have “a wonderful, wonderful facility of mind, reducing problems to their simplest form, all the while supporting his own talent”. Rather poetically, Edwards also described “spreading great goodness to others on the side”.

The story of the conversation between Edwards and John when the two met for the first time to train each other is also immortal. Edwards asked how John liked to deliver the ball. “You wear it, I’ll get it,” came the phlegmatic reply.

Another element is Gerald Davies, a respectable winger of that era, who marvels at Sean’s ability. “Although the drive went on around him, he could separate himself from it,” Davies once said. “He kept his emotions in check and carefully restrained the action around him. The game would go according to his will and anyone else’s.”

At no time was that influence more evident than in 1971. In the third Test against the All Blacks in Wellington, John scored a try which was brilliantly set up by Edwards and the Lions prevailed 13-3. A 14-14 draw at Eden Park in the fourth encounter saw the Carwyn James-coached tourists take the lead in the series. They remain the only Lions team to win a Test series in New Zealand. As a sign of John’s performance, which included goalkeeping in Christchurch and Wellington, he accounted for 30 of the 48 points scored by the Lions over four Tests.

Also part of John’s impressive catalog of highlights is a sweeping finish against England in 1969, which came off the back of Keith Jarrett’s rallying chip and inspired Wales to a 30-9 run which sealed the Triple Crown.

Earlier in the competition, at Murrayfield, he was charged by Scotland halfback Colin Telfer and sold a wicked dummy to go in under the posts. Only an 8-8 draw in the Colombes would prevent a Grand Slam, which Wales achieved in 1971.

Of course, John was the main architect, recording points in all four games including a try against Scotland and France. No wonder it got audiences drunk. It’s no wonder the memories have outlasted his relatively short career and will live on for some time to come.