If ever there was a year to call for bold global action on climate change, 2023 was it.

In what is likely to go down as the hottest year on record – one filled with catastrophic floods, crippling heat waves, devastating wildfires and persistent drought – leaders from nearly 200 countries gathered to chart a way forward in the fight against climate change. to trace.

After more than two weeks of intense negotiations at the United Nations Conference on Climate Change, known as COP28, in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, representatives from 198 countries agreed on Wednesday to “transition” from fossil fuels.

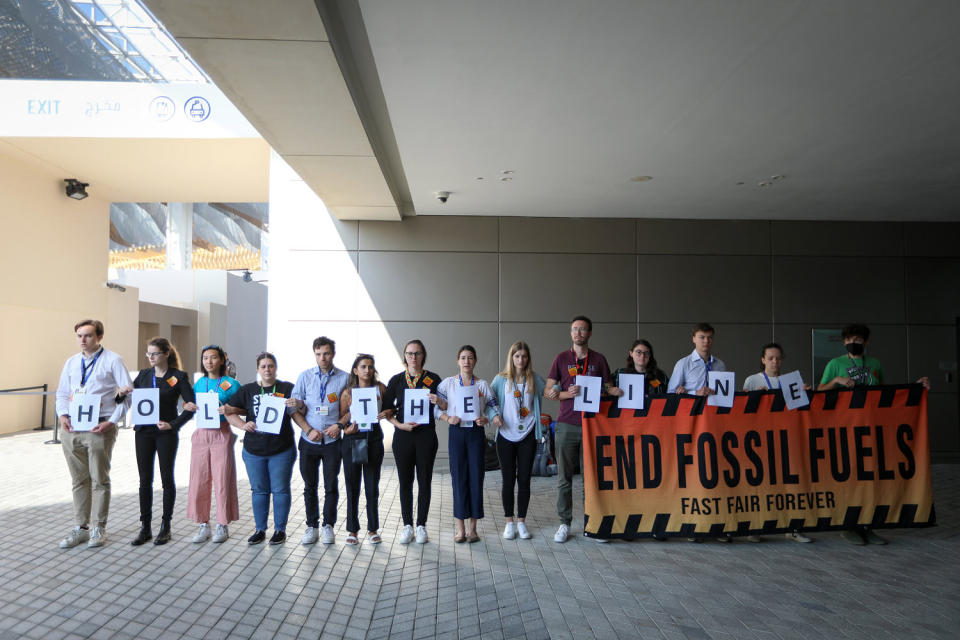

It was a historic move but one that again fell short for many climate activists, who saw it as further evidence that efforts to address climate change are moving too slowly and that fossil fuel interests are at risk.

Former Vice President Al Gore hailed the deal as an “important milestone” but said the role of fossil fuel burning in the climate crisis is “the bare minimum we need and it’s beyond term” to identify.

“Whether this is the tipping point that truly ushers in the beginning of the fossil fuel era depends on the actions that come and the financial mobilization needed to achieve them,” Gore wrote Wednesday on the social media platform X.

Doubts about what will happen next are understandable. The COP Agreement’s lack of a concrete plan to end the use of fossil fuels adds to the growing concern that the major measures necessary to avoid dire environmental consequences are on the way. Certainly, the rise of clean energy technology and wider social awareness of global warming have inspired some optimism, but many environmentalists stress that these developments may mean little without a significant reduction in the amount of carbon dioxide which is pumped into the atmosphere.

United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres said on Wednesday that “the era of fossil fuels must end,” adding that science shows it will be impossible to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) indefinitely. put to their use.

“Whether you like it or not, the gradual end of fossil fuel is inevitable,” he wrote on X. “Let’s hope it’s not too late.”

The COP28 climate summit was controversial from the start. The host country, the UAE, is an oil-rich nation, and the meeting’s president, Sultan al-Jaber, is the chief executive of the UAE’s state oil company, ADNOC.

Early in the conference, Al-Jaber came under fire for claiming in an online event in late November that there was “no science” to support the need to phase out fossil fuels to limit global warming , as first reported by The Guardian.

The event came as belief that oil companies are committed to reducing fossil fuel emissions has waned. Although major oil and gas companies have previously indicated that they would switch to clean energy and do their part to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, they have backed off many of those claims over the past year. Critics have accused the industry of “greening,” as companies ramped up exploration and approved hundreds of new oil and gas projects around the world.

During the meeting, which included overtime talks, critics questioned how much could be achieved on fossil fuels when it was held in Dubai and chaired by Al-Jaber. Those concerns came to the fore when it became clear that the final agreement would not promise to phase out fossil fuel.

Although the phrases “move away” and “step out” sound similar, there are key distinctions between them. Phase-out means that their use in energy systems will eventually cease, while “phase-out” is a compromise that implies that their use will be reduced but still continue.

Nate Hultman, a former State Department official and founder and director of the Center for Global Sustainability at the University of Maryland, said it was an open question at the conference whether world leaders would seriously debate the future of fossil fuels.

“There was a risk that this could be an exercise in avoiding the issue,” he said.

But Hultman said it is clear in the final agreement – which requires countries to “transition” from fossil fuels in an equitable manner, triple the amount of renewable energy installed by 2030, and emissions of the potent greenhouse gas methane – to include accomplished. World leaders consider a future without fossil fuels.

“The result shows that not only was this issue discussed substantially, but it was highlighted in the text. There are good, strong elements there,” said Hultman, who attended his 21st COP this year. “It will be important to send this kind of signal when it comes to transitioning away from fossil fuels.”

Still, the agreement is non-binding and its critics – in particular, leaders from poor countries, developing countries and island nations disproportionately affected by climate change – say it does not go far enough to eliminate fossil fuels and the world to keep below 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming.

Many scientists and climate activists have expressed frustration that calls to “phase out” fossil fuels have been significantly reduced.

“The agreement that emerged from COP28 rightly emphasizes nature as a solution, but the failure to acknowledge the need to phase out the use of fossil fuels is disrespectful,” Mustafa Santiago Ali, executive vice president of conservation and justice at the non-profit National Wildlife Federation, said in a statement on Wednesday.

Earlier in the week, as drafts of the agreement emerged, emotions ran even higher. Gore wrote on Monday the X that “COP28 is now on the verge of complete failure.”

In the end, nations agreed for the first time in nearly 30 years of these UN summits that a transition away from fossil fuels was necessary to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by or around 2050 and to avoid the worst consequences of climate change.

It was suggested that it was a major milestone just to mention the elephant in the room at previous COP meetings.

“It was hard to imagine five years ago that the phase-out of fossil fuels is now at the center of the stage and it is a significant step forward,” said Michael Lazarus, senior scientist and director of the US Stockholm Environmental Institute. , based in Seattle. “It means that fossil fuels now have a shelf life, a due date. We are at a point where we can envision a transition away from fossil fuels.”

Lazarus said the consensual nature of the international process – that every country participating in discussions has veto power – is a major contributor to global progress.

“People talk about it being just words and not action, but the discourse that comes out of these international meetings has great resonance and the ability to change the conversation,” said Lazarus. “If we don’t have a sense of global action to phase out fossil fuels, to reduce emissions worldwide, countries won’t have the same incentives to act in the ways they need to.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com