Scientists may have identified a molecule that played a key role in robbing Venus of water and turning this planet into the horrible, hellish world we see today.

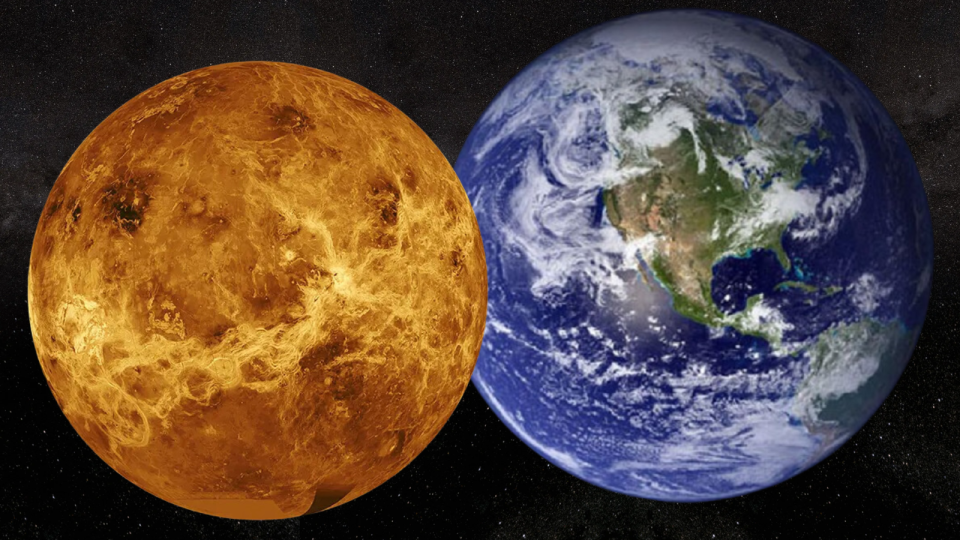

Venus is often called a “twin world” because the two planets are about the same size and density; both are rocky planets located in the inner region of the solar system. But, in many crucial ways, Venus could not be more like Earth.

Although our planet is teeming with life, Venus, the second planet from the sun, is a virtual hell. It is the hottest planet in the solar system (even hotter than Mercury, which is close to the sun), with a temperature of around 880 degrees Fahrenheit (471 degrees Celsius). That’s hot enough to melt lead. In addition, Venus has tremendous surface pressures.

Importantly, Venus lacks a key element for life that is abundant here on Earth: Water. This is despite the planet being within the sun’s so-called “Goldilocks Zone”, the region around our star that is neither too hot nor too cold to host liquid water – and it’s just as well despite the fact that the scientists know. Venus probably had water.

Related: Zoozve – a strange ‘moon’ of Venus that earned its name by accident

In fact, billions of years ago, Venus is believed to have had as much water as Earth – but, at some point in its evolution, carbon dioxide clouds in the planet’s atmosphere triggered the most intense greenhouse effect on the solar system. This caused very high temperatures to the point where they are seen today. This caused the planet’s water to evaporate, which was then lost to space.

Even taking this process into account, however, scientists do not know how Venus became so desert-like or how it is still losing what little water it has left to space. Now, a team of scientists from the University of Colorado Boulder may have discovered the secrets of this process by telling what they call “the story of water on Venus.”

“Water is absolutely essential to life,” Eryn Cangi, joint team leader and scientist with the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP), said in a statement. “We need to understand the conditions that support liquid water in the universe and the very dry state of Venus may have occurred today.

“We’re trying to figure out what small changes happened to each planet to drive them into these different giant states.”

Hey, neighbor! Spare a cup of water?

To put into context the difference between the water content of planetary neighbors Earth and Venus, Cangi explained that if all the water on our planet were spread evenly over its surface, it would form a global layer nearly 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) on depth. If Venus were to do the same, removing the remaining water from the atmosphere would create a global layer only 1.2 inches (3 centimeters) deep.

“Venus has 100,000 times less water than Earth, although it is basically the same size and mass,” Michael Chaffin, leader of the joint team and co-scientist LASP, explained in the statement.

In order to determine how it reached its current state, Cangi, Chaffin and colleagues used computer models of the planet, treating it almost like a giant chemistry laboratory. This allowed them to better observe the various reactions that occur in the swirling atmosphere of Venus and to identify a suspected water loss.

What the team discovered is that a molecule called HCO+ – made up of a hydrogen atom, a carbon atom and an oxygen atom – high in the atmosphere of Venus, could be responsible for delivering the planet’s last water to space.

“As an analogy, say I dumped out the water in my water bottle,” said Cangi. “There would still be a few drops left.”

HCO+ could essentially remove these droplets from the atmosphere of Venus. In fact, the same team previously suggested that HCO+ was the culprit causing Mars, Earth’s other neighbor, to lose its water.

The researchers say that HCO+ is constantly produced in the atmosphere of Venus, but these ions do not last long. An ion is a positively or negatively charged molecule, having earned its charge due to the lack of some electrons necessary to balance the positive charge of its proton, or having additional electrons to create a net negative charge in the molecule.

HCO+ lacks an electron to balance the positive charge of the molecule’s protons, so it is positively charged (hence the + symbol).

Electrons in the Venusian atmosphere combine with HCO+ quickly, causing the molecule to split in two. From there, the team argues that the hydrogen atoms zip away and perhaps even escape into space. Hydrogen atoms form two of the constituents of the water molecule (H2O), which consists of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom, so this robs Venus of the primary constituents of water.

The team thinks that for Venus to reach its extreme dry state, the planet must have an excess of HCO+ molecules in its atmosphere.

“One of the surprising conclusions of this work is that HCO+ should be among the most abundant ions in the atmosphere of Venus,” Chaffin said.

However, there is a major caveat to this conclusion. So far, we have not seen HCO+ in the atmosphere of Venus.

Chaffin and Cangi don’t think that’s the reason the molecule doesn’t exist, however, but because humans haven’t had the tools to see it. Although many spacecraft from Earth have visited Earth’s neighbor Mars, very few missions have visited our other neighbor Venus – and none of those have been properly equipped to see HCO+.

Related Stories:

— Life on Venus? Interesting molecule phosphine appears in planetary clouds again

— If Venus had Earth-like plate tectonics in the past, did it also have life?

— The Magellanic Clouds must be renamed, astronomers say

But some future space missions are setting their sights on Venus. Of particular importance is NASA’s Noble Gas Exploration, Chemistry and Imaging (DAVINCI) mission of the Deep Atmosphere of Venus. To be launched in 2029, DAVINCI will launch a probe through the hot atmosphere of Venus’ crust to determine the chemical composition of the earth.

However, DAVINCI will not even have the right equipment to detect HCO+.

However, the team hopes that thanks to DAVINCI (and the upcoming European Space Agency’s EnVision mission) general interest in Venus will eventually lead to a space mission capable of detecting HCO+, which adds truth to the team’s water loss story. .

“Not many missions have been sent to Venus,” Cangi said. “But newly planned missions will draw on decades of collective experience and blossoming interest in Venus to explore the extremes of planetary atmospheres, evolution and habitability.”

The team’s research was published on Monday (May 6) in the journal Nature.