About 400,000 years ago, large parts of Greenland were free of ice. Scrubbed tundra bathed in the sun’s rays on the highlands of the northwest of the island. Evidence suggests that southern Greenland was once covered by a forest of spruce trees, which bore bald insects. Global sea levels were much higher then, between 20 and 40 feet above today’s levels. All over the world, land inhabited by hundreds of millions of people was under water.

Scientists have known for some time that the Greenland ice sheet had largely disappeared at some point in the past million years, but not exactly when.

In a new study in the journal Science, we set the date, using frozen soil removed during the Cold War from beneath a nearly mile-thick section of the Greenland ice sheet.

The timing – about 416,000 years ago, with largely ice-free conditions lasting up to 14,000 years – is important. At that time, the Earth and its early humans were going through one of the longest interglacial periods since the ice sheets covered the high latitudes 2.5 million years ago.

The duration, extent and effects of that natural warming can help us understand the Earth that modern humans are creating for the future.

A preserved world under the ice

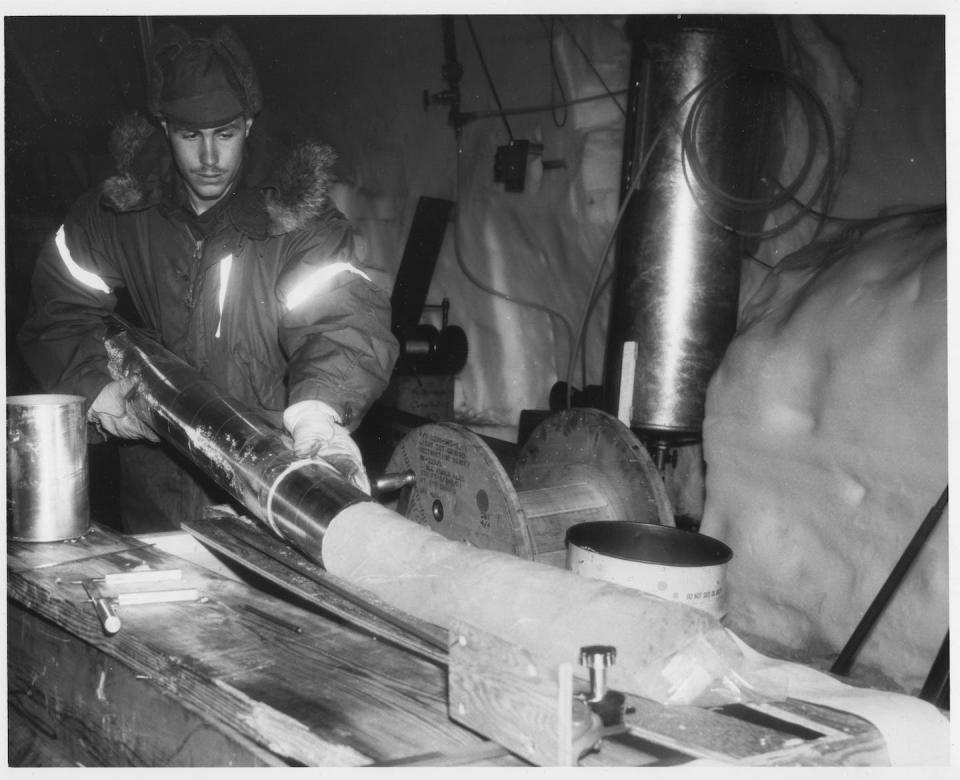

In July 1966, American scientists and US Army engineers began a six-year effort to drill into the Greenland ice sheet. The drill was taking place at Camp Century, one of the army’s most unusual bases – it was nuclear powered and consisted of a series of tunnels dug into the Greenland ice sheet.

The drilling site was in northwest Greenland 138 miles from the coast and under 4,560 feet of ice. Once they reached the bottom of the ice, the team continued to drill another 12 feet into the frozen rocky soil below.

In 1969, geophysicist Willi Dansgaard’s analysis of the ice core from Camp Century revealed for the first time data on how the Earth’s climate has changed dramatically over the past 125,000 years. Extended periods of cold glaciers when the ice expanded rapidly followed by warmer interglacial periods when the ice melted and sea levels rose, flooding coastal areas around the world.

For nearly 30 years, scientists paid little attention to the 12 feet of frozen soil from Camp Century. One study analyzed the pebbles to understand the bedrock beneath the ice sheet. Another interestingly suggested that the frozen soil preserved evidence of a warmer time than today. But with no way to date the material, few people paid attention to these studies. By the 1990s, the core of the frozen soil had disappeared.

Several years ago, our Danish colleagues found the lost soil deep in the Copenhagen freezer, and we formed an international team to analyze this unique frozen climate archive.

In the top example, we found perfectly preserved fossil plants – proof positive that the land far below Camp Century was ice-free sometime in the past – but when?

Going with old rock, twigs and dirt

Using samples cut from the center of the sediment core and prepared and analyzed in the dark so that the material retained an accurate memory of its last exposure to sunlight, we now know that the ice sheet a covers northwest Greenland – nearly a mile thick today – disappeared during the naturally warm extended period known to climate scientists as MIS 11, between 424,000 and 374,000 years ago.

To determine more precisely when the ice sheet melted, one of us, Tammy Rittenour, used a technique called luminescence dating.

Over time, minerals accumulate energy as radioactive elements such as uranium, thorium, and potassium decay and release radiation. The longer the sediment is buried, the more radiation it collects as trapped electrons.

In the laboratory, specialized instruments measure small bits of energy, which are emitted as light from these minerals. That signal can be used to calculate how long the grains were buried, since the trapped energy would be released with the final exposure to sunlight.

Paul Bierman’s lab at the University of Vermont dated the last time the sample was near the surface in a different way, using rare radioactive isotopes of aluminum and beryllium.

These isotopes form when cosmic rays, coming from far away from our solar system, strike the Earth’s rocks. Each isotope has a different half-life, meaning it decays at a different rate when placed.

By measuring both isotopes in the same sample, glacial geologist Drew Christ was able to determine that the sediment had been exposed to melting ice at the land surface for less than 14,000 years.

Ice sheet models run by Benjamin Keisling, which incorporate our new knowledge that Camp Century was ice-free 416,000 years ago, show that the Greenland ice sheet must have shrunk significantly then.

At least the edge of the ice rose from tens to hundreds of miles around much of the island during that period. Water from that melting ice raised global sea levels by at least 5 feet and possibly as much as 20 feet compared to today.

Warnings for the future

The ancient frozen soil beneath the Greenland ice sheet warns of trouble ahead.

During the MIS 11 interglacials, the Earth was warm and ice sheets were limited to the high latitudes, much like today. Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere remained between 265 and 280 parts per million for about 30,000 years. MIS 11 lasted longer than most interglacials due to the influence of the shape of the Earth’s orbit around the sun on the solar radiation that reaches the Arctic. Over these 30 millennia, that level of carbon dioxide has fueled enough warming to melt much of Greenland’s ice.

Today, there is 1.5 times more carbon dioxide in our atmosphere than in MIS 11, about 420 parts per million, a concentration that has been rising every year. Carbon dioxide traps heat, warming the planet. Too much of it in the atmosphere raises the global temperature, as the world is seeing now.

Over the past decade, as greenhouse gas emissions continued to rise, humans experienced the eight warmest years on record. July 2023 was the hottest week on record, based on preliminary data. Such heat melts ice sheets, and the loss of the ice causes the planet to become larger as dark rock soaks up the sunlight that once reflected bright ice and snow.

Even if everyone stopped burning fossil fuels tomorrow, carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere would be elevated for thousands and thousands of years. That’s because it takes a long time for carbon dioxide to move into soils, plants, the ocean and rocks. We are creating conditions conducive to a very long period of heat, just like MIS 11.

If humans do not significantly lower the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the evidence we have found about Greenland’s history suggests a largely ice-free future for the island.

Everything we can do to reduce carbon emissions and sequester carbon already in the atmosphere will increase the chances of the Greenland ice sheet surviving longer.

The alternative is a world that could look a lot like MIS 11 – or even more extreme: A warming Earth, shrinking ice, rising sea levels, and waves rolling over Miami, Mumbai, India and the Venice, Italy.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world.

It was written by: Paul Bierman, University of Vermont and Tammy Rittenour, Utah State University.

Read more:

Paul Bierman receives funding from the US National Science Foundation.

Tammy Rittenour receives funding from the US National Science Foundation.