-

2,000-year-old bones provide evidence against the idea that Columbus brought syphilis to Europe.

-

The conquistadors have long been blamed for the European outbreak of STIs in the late 1400s.

-

But DNA analysis doesn’t add up to that story, a new study has found.

The idea that Christopher Colombus brought syphilis back from the New World may be completely wrong.

It was long hypothesized that the Spanish conquistadors picked up the sexually transmitted infection (STI) and brought it to Europe in the late 1400s.

But a paper published Wednesday in the peer-reviewed journal Nature adds to a growing body of evidence that the conquistadors did not spread the disease after their invasion of what is now South America.

Instead, the bacteria could have evolved much earlier than previously thought, Verena Schünemann, professor of Paleogenetics from the University of Basel, told Business Insider.

“Of course, we can’t prove it wrong – it still doesn’t work. But it seems that a much more complex story is developing than these hypotheses currently capture,” she told BI.

There is some doubt about the time of the arrival of syphilis in Europe

Looking at historical literature, you’d think syphilis must have arrived with the conquistadors.

There was a major outbreak of syphilis in Europe in the late 1400s, mostly in harbor towns, apparently out of the blue.

This was cause for doubt when the sailors who accompanied Columbus on his journey to South America returned.

Prior to that the records of syphilis outbreaks were poor. Later excavations in South America revealed bones that bore lesions typically associated with syphilis infection.

Overall, this has encouraged historians to view the voyage as an early example of how infections can spread across the globe.

Except, it’s probably not that simple.

Later observations suggested that some skeletons found in European sites may carry lesions typically associated with syphilis infection, long before first contact with pre-Columbian native Americans.

As the plot develops, scientists have begun to look to more modern methods of investigation to find out what really happened.

DNA analysis reveals a more complicated story

To better understand the history of syphilis, Schünemann and her colleagues looked at 2,000-year-old bones bearing the characteristic lesions, found about 20 years ago in what is now Brazil.

They drilled small holes in the lesions using dental instruments and extracted the ancient DNA left behind by the bacteria in the bone.

The analysis found that some of these lesions were not caused by the bacteria behind sexually transmitted syphilis, but by a closely related cousin.

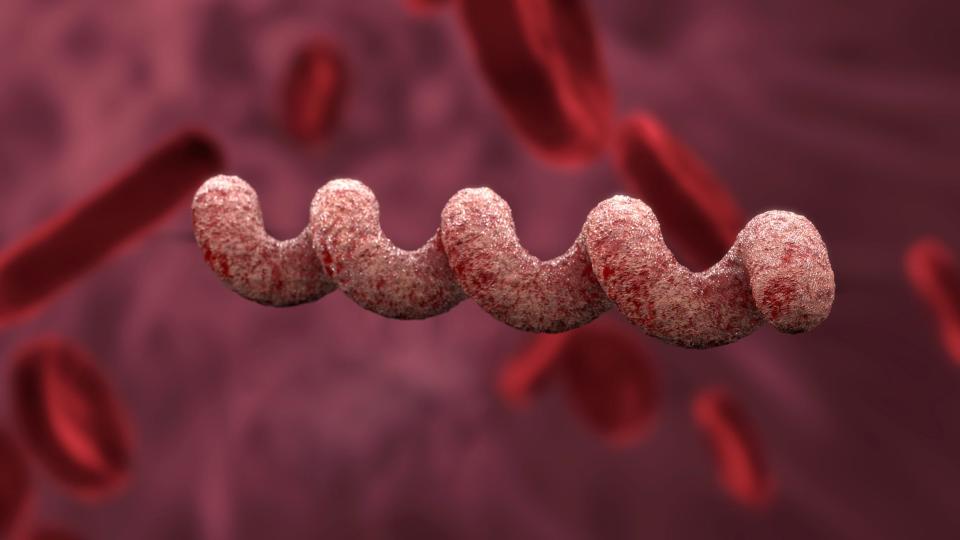

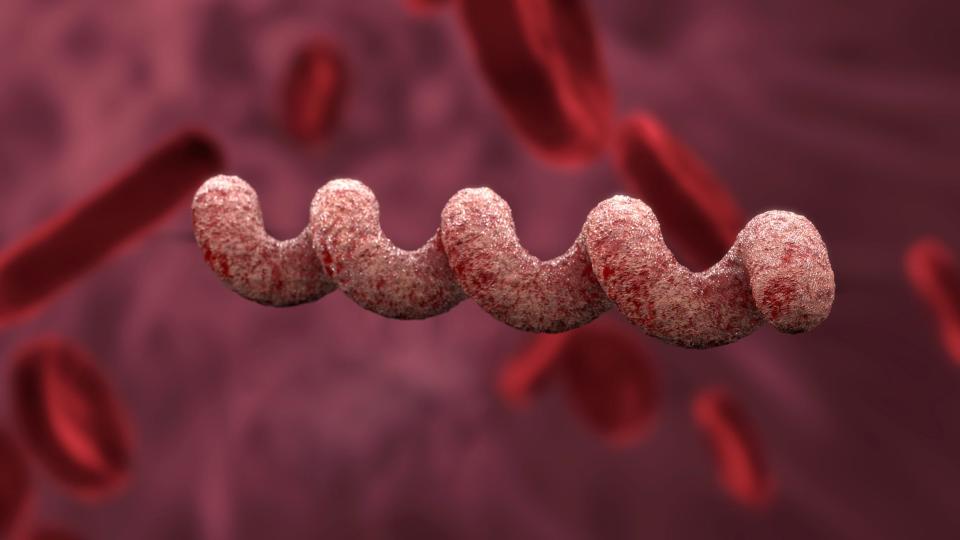

Although this microbe is very similar to the one behind syphilis – it is part of the same family, called Treponema – it causes a completely different disease, called Bejel, which is not sexually transmitted.

It is still around today, mainly in Asia and Japan.

“We didn’t expect to find him there,” Schünemann said.

“Usually it’s in arid regions, not so much in those humid coastal, tropical regions. That’s why we were quite surprised – this is a completely different environment than what you expect to find him,” she said.

This suggests that the bone lesions alone do not guarantee that syphilis was present in South America before Columbus, putting holes in the evidence used to support the hypothesis.

The study is “really exciting because it is the first truly ancient treponemal DNA obtained from archaeological human remains that are more than a few hundred years old,” says Brenda Baker at Arizona State University, according to New Scientist.

The mystery remains

The results do not definitively close the door on the Columbus theory. But they provide valuable clues to better understand what happened.

“It helps us indirectly,” said Schünemann.

With this ancient genome, Schünemann and colleagues were able to discover that the entire Treponema family is much older than expected.

The analysis suggests that these closely related bacteria have a common ancestor around 14,000 years ago, Schünemann said.

This means that these bacteria could have traveled around the world several times with the various human migrations, much earlier than the voyage of Columbus.

“We can play around now and say, okay, what hypothesis can we possibly develop from that?” said Schünemann

For Schünemann, it is likely that the bacteria that cause syphilis, Bejel, and other cousins of the Treponema family were already around in Europe, India, and America, long before the first contact between Columbus and native Americans.

“I think there’s a definite chance they were around before the encounter,” she said.

It will be interesting, she said, to try to do the same analyzes on European bones bearing lesions and find even older samples that might paint a better picture of the Treponema family tree.

The importance of the work goes beyond solving this historical mystery. Syphilis and its cousins are still rampant throughout the world today.

Although they are being kept under control by antibiotics, they are quickly learning to ignore the treatments.

If left untreated, syphilis can cause permanent damage to the heart, brain and other internal organs. Bejel, or yaws, is a childhood disease that can be disfiguring and disfiguring.

By looking back at how it evolved with humans in the past, such as how microbes pass genetic information back and forth, we can better predict how it will evolve in the future.

“When it comes now to this increase in antibiotic resistance and so on, it can help in the future to develop new strategies to fight this bacterium,” she said.

Read the original article on Business Insider