When you make a purchase through links on our article, Future and its syndicate partners may earn a commission.

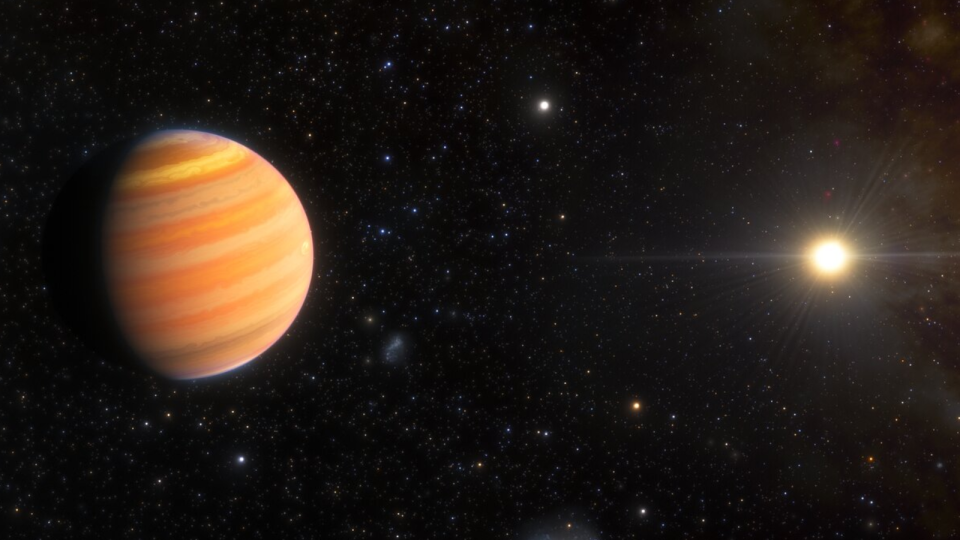

There is more than meets the eye for a distant gas giant planet.

Astronomers have discovered that the extrasolar planet, or “exoplanet,” not only has one of the strangest orbits ever seen, but is turning into a “hot Jupiter” world. Understanding this transformation could help scientists create a better picture of how life in this strange class thrives.

The exoplanet, named TIC 241249530 b and located about 998 light-years from Earth, was first observed by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TSES) in January 2020 when it crossed, or “transited,” the face of mother star.

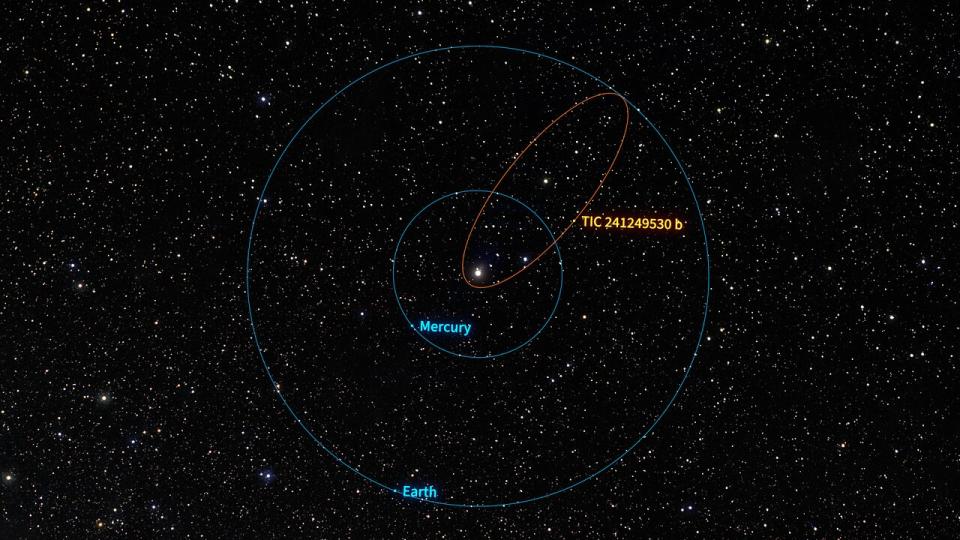

The planet orbits its star, TIC 241249530, about 12% of the distance between Earth and the sun. That proximity means it completes an orbit in 15.2 Earth days. But that’s not what’s so extreme about this planet’s orbit.

Related: Evidence of water found in the atmosphere of a mysterious ‘metal god of war’ exoplanet

Most planets do not have perfectly circular orbits. Rather, most planetary orbits are elliptical with some degree of flattening, which astronomers call “eccentricity.” TIC 241249530 b has one of the most extended orbits astronomers have ever seen. Furthermore, the Jupiter-sized planet is orbiting its star “backward” relative to the star’s rotation.

However, hot Jupiters are exoplanets that orbit their planets at distances that make them complete a year in 10 Earth days or less. That means TIC 241249530 b is not a hot Jupiter – at least, not yet. Currently, how hot Jupiters come so close to their parent stars is a source of encouragement to astronomers, and scientists are suggesting these planets form further away from their stars and then migrate inward.

However, even after astronomers have seen and confirmed at least 5,600 exoplanets, the early stages of this migration process are still very elusive.

A team of astronomers used two instruments on the WIYN 3.5-meter Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO) to observe TIC 241249530 and reveal it as a hot early Jupiter.

“Astronomers have been searching for exoplanets that are likely precursors to a hot Jupiter, or intermediate products of the migration process, for over twenty years, so I was very surprised – and excited – to find one,” team leader Arvind Gupta, a NOIRLab postdoctoral researcher, said in a statement. “It’s exactly what I was hoping to get.”

Hot Jupiter in the making

The scientists first used the NN-EXPLORE Exoplanet and Stellar Speckle Imager (NESSI) to remove “twinkling” patterns caused by Earth’s atmosphere, as well as reduce noise from other light sources that could distort the signal. to pollute from the star TIC 241249530 as his. planet shifted its face.

Then, they measured the exoplanet’s velocity around the star using the NEID spectrograph to determine the transfer of light from the star.

“NESSI gave us a sharper view of the star than would have been possible otherwise, and NEID precisely measured the star’s spectrum to detect changes in response to the orbiting exoplanet,” Gupta said.

The team’s analysis of this spectrum confirmed that the mass of TIC 241249530 b is about five times that of Jupiter. The investigation also revealed the planet’s highly eccentric orbit. The eccentricity of a planet’s orbit is measured on a scale from 0 to 1, with 0 being a perfectly circular orbit and 1 being a highly elliptical orbit.

Pluto’s highly elliptical orbit around the sun, for context, has an eccentricity of 0.25, while Earth’s nearly circular orbit has an eccentricity of 0.02. The orbit of TIC 241249530 b has an eccentricity of 0.94, which is more eccentric than the orbit of any other exoplanet ever discovered by the exoplanet transit method.

Another planet in particular with a flatter orbit, HD 20782 b, is a gas giant located 1117 light years away. Their orbit has an eccentricity of 0.956, but this world was not discovered using the transit method.

If TIC 241249530 b were placed in the solar system, its orbit would bring it 10 times closer to the sun than Mercury (which is about 3 million miles, or 4.8 million kilometers) and then right out to Earth’s maximum distance from the sun (about 95 million miles, or 153 million kilometers). This would cause temperature variations on TIC 241249530 b to swing from those associated with a nice summer day on Earth to hot enough to melt lead.

The motion of TIC 241249530 b around its star also had another unusual feature. The planet orbits its star in the opposite direction to the star’s rotation, which is called “retrograde motion.” This is rarely seen on exoplanets and is only exhibited by two planets in the solar system, Venus and Uranus.

These two aspects of the orbit of TIC 241249530 b have put the team off until they can change hot Jupiter. The team thinks that as this highly volatile orbit brings the planet close to its star, the orbit will begin to fill in like the 2D shadow of an inflating beach ball. This is expected to happen because tidal forces generated by the star’s gravity pull orbital energy away from the exoplanet.

As the planet’s orbit “circles,” it will also contract, pulling TIC 241249530 b closer to its star and giving it a year that lasts less than 10 Earth days, indicating that the transformation to hot Jupiter completed.

Related Stories:

— NASA space telescope finds an Earth-sized exoplanet that isn’t a ‘bad’ place to hunt for life

— A giant ‘hot Jupiter’ exoplanet flows like rotten eggs and has raging glass storms

— NASA exoplanet hunter discovers ‘strange’ world living off relentless bombardment of stars – it’s called the Phoenix

TIC 241249530 b is just the second exoplanet discovered that appears to be in Jupiter’s warm premigration phase. TIC 241249530 b and the previous example of such a hot Jupiter progenitor seem to support the transformation of high-mass gas giants into hot Jupiters by their transition from highly eccentric to tighter, more circular orbits.

“Although we can’t force rewind and watch the process of planetary migration in real time, this exoplanet acts as a kind of snapshot of the migration process,” Gupta concluded. be rare and hard to find, and we hope it can help us solve the hot story of Jupiter’s formation.”

The team’s research was published on July 17 in the journal Nature.