About five and a half thousand years ago, northern Africa went through a major change. The Sahara desert expanded and grasslands, forests and lakes that people preferred disappeared. People had to retreat to the mountains, the axes, and the Nile valley and delta.

Because a relatively large population was dispersed into smaller and more fertile areas, it had to innovate new ways to produce food and organize society. Soon after, one of the world’s first great civilizations emerged – ancient Egypt.

This transition from the most recent “humid African period”, which lasted from 15,000 to 5,500 years ago, to the current dry conditions in northern Africa, is the clearest example of a climatic tipping point in recent geological history . Climate tipping points are thresholds that when crossed lead to a dramatic climate change to a new stable climate.

Our new study published in Nature Communications reveals that before northern Africa dried out, its climate “flickered” between two stable climate states before permanently collapsing. This is the first time such a hawthorn has been shown in the past on Earth. And it suggests that places with highly variable cycles of climate change today may in some cases be leading their own tipping points.

One of the biggest concerns of climate scientists today is whether we will have any warnings of climate tipping points. As 1.5˚C global warming approaches, the most likely tipping points are likely to be hearing of ice sheets in Greenland or Antarctica, dying tropical coral reefs, or sudden melting of permafrost in the Arctic.

Some say there will be warning signs of these major climate changes. However, these are highly dependent on the actual type of tipping point, and therefore these signals are difficult to interpret. One of the big questions is the nature of the flickering tipping points or whether the climate will appear to become more stable first before arriving in one go.

620,000 years of environmental history

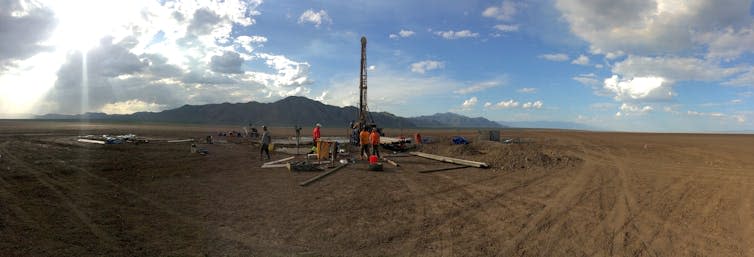

To investigate further, we assembled an international team of scientists and went to the Chew Bahir bay in southern Ethiopia. There was an extensive lake here during the last humid African period, and sedimentary deposits, several kilometers deep, beneath the lake bed accurately record the history of climate-driven changes in lake level.

Today, the lake has largely disappeared and the deposits can be drilled relatively cheaply without the need for a drilling rig on a floating platform or a drillship. We drilled 280 meters below the bottom of the dry lake – almost as deep as the Eiffel Tower is tall – and removed hundreds of mud tubes around 10 centimeters in diameter.

By putting these tubes together in order they form a so-called sedimentary core. That core contains vital chemical and biological information that records the past 620,000 years of eastern Africa’s climate and environmental history.

We now know that there was about 1,000 years when the climate was changing regularly at the end of Africa’s wet period when it was very dry and wet.

In total, we observed at least 14 dry phases, each lasting between 20 and 80 years and repeated at intervals of about 160 years. Later there were seven wet phases, of similar duration and frequency. Finally, around 5,500 years ago a dry climate prevailed for good.

Climate break

These high-frequency, wet-dry extreme fluctuations indicate clear climate fluctuations. Such devastation can be imagined in climate model computer programs and has also occurred in earlier climate transitions at Chew Bahir.

We see the same types of flickering during a previous change from a humid to a dry climate around 379,000 years ago in the same sediment core. It looks like a perfect copy of the transition at the end of the African humid period.

This is important because this transition was natural, as it happened long before humans had any impact on the environment. Knowing that such a change could occur naturally counters the argument made by some academics that the introduction of livestock and new agricultural techniques may have accelerated the end of the last wet period in Africa.

On the contrary, there was no doubt that climate tipping had an impact on people in the region. The flicker, which one could easily see, would have a dramatic effect compared to the slow climate change over thousands of generations.

It could explain, perhaps, why the archaeological findings in the region are so different, even contradictory, at times of transition. People retreated during the dry phases and then some came back during the wet phases. Eventually, people retreated to places that were consistently wet like the Nile valley.

It is important that the climate flicker is confirmed as a precursor to a major climate collapse because it may also provide insight into possible early warning signs of major climate changes in the future.

It seems that highly variable climate conditions such as rapid wet-dry cycles may warn of a significant change in the climate system. Identifying these precursors now may provide the warning we need that future warming will take us to one of the sixteen climate tipping points identified.

This is particularly important for regions such as eastern Africa where almost 500 million people are already at great risk from impacts caused by climate change such as drought.

This article from The Conversation is republished under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Martin H. Trauth receives grant funding from DFG, ICDP, NERC and NSF. Martin H. Trauth is an active member of DGGV and EGU.

Asfawossen Asrat receives funding from ICDP, NSF, NERC

Mark Maslin is the designated UNFCCC point of contact for UCL. He is co-director of the NERC London Doctoral Training Partnership and a member of the Climate Crisis Advisory Group. He is a member of the Sopra-Steria CSR Board, Sheep Included Ltd, Lansons and NetZeroNow advisory boards. He has received grant funding from NERC, EPSRC, ESRC, DFG, Royal Society, DIFD, BEIS, DECC, FCO, Innovate UK, Carbon Trust, UK Space Agency, European Space Agency, Research England, Wellcome Trust, Leverhulme Trust, CIFF , Sprint2020, and the British Council. He has received funding from the BBC, Lancet, Laithwaites, Hearst, Seventh Generation, Channel 4, JLT Re, WWF, Hermes, CAFOD, HP and the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors.