When the dinosaurs roamed the land, the skies above them were filled with a variety of soaring reptiles, which swept through the air on thin, bright wings. These animals, pterosaurs, were not dinosaurs, but their evolutionary cousins.

We have just announced the discovery of a new species of pterosaur almost 15 years after a fossil was discovered on the Isle of Skye. It is one of the most complete pterosaur fossils to be found in the UK since the first one was discovered off the Dorset coast in 1828 by palaeontologist Mary Anning.

Pterosaurs were the first vertebrate animals to achieve powered flight (insects came first). Pterosaur fossils are known throughout the world but their remains are rare compared to their land and water based relatives. This is due to the fragile nature of their skeleton, which is made up of thin, thin-walled bones.

Pterosaur fossils are often incomplete, crushed and distorted. Anning’s discoveries have yielded a sparse record of pterosaurs from the Jurassic period (200-145 million years ago) and Cretaceous period rocks (145-66 million years ago) in the UK.

But most of these are limited to a few isolated bones like Vectidracoa toothless pterosaur whose fossil remains were found on the Isle of Wight in 2008 by five-year-old Daisy Morris.

This is where Skye comes in. Although Skye is most famous for the ancient volcanic landscape of the Cullinan Hills, Jurassic age rocks surround the edge of the island.

Over the past 50 years teams of geologists and palaeontologists have gradually been uncovering more of the ancient history of the Isle of Skye. This work has been accelerated thanks to the new imaging techniques, mainly CT scanning, which facilitate the study of these fossils.

Our new pterosaur was discovered in 2006 by a team of researchers including Paul Barrett in a loose shell lying on the beach at Claddagh a’Glinne, on the edge of a remote bay overshadowed by Cullinton.

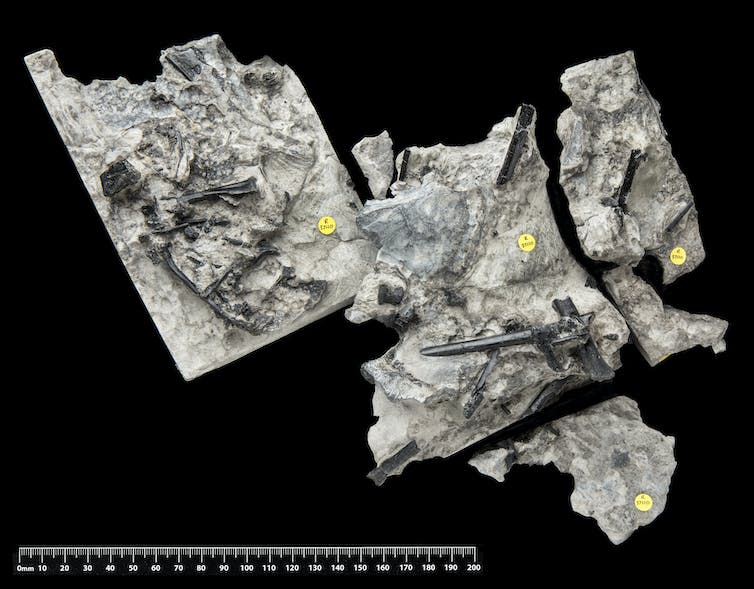

At first glance, the new skeleton was a smear of thin, broken, black bone set in hard, dark gray mudstone. But, even then, these thin bones indicated that the find would be interesting.

It took Lu Allington-Jones, one of the Natural History Museum’s fossil technicians, almost two years to prepare our discovery for study. The rocks from Skye are extremely hard, and the fossil bones are delicate.

While Lu’s work allowed us to study some of the bones, others were still encased in rock because they were too fine to remove or expose further.

When this work was completed, the specimen lay dormant in the museum’s collections for approximately nine years. But then we decided to examine the fossil using the university’s CT scanner.

Using this equipment, similar to that used in a hospital to diagnose broken bones, over many months of careful imaging we were able to reveal almost the entire animal in three dimensions.

After comparing it to other pterosaur fossils from around the world, we realized we were dealing with something new and called it Ceoptera Evans (from the Gaelic name Skye, Eilean a’ Cheò, Isle of Mist, and a tribute to Professor Susan Evans who has done a lot of work in the area).

This pterosaur species is important because of the quality of its preservation and its age. It is one of a handful of pterosaur skeletons from the Middle Jurassic period, around 167 million years ago.

At this time pterosaurs were undergoing huge anatomical changes from the early small-bodied, long-tailed pterosaurs, for example Demorphodon (about the size of a raven) to later pterosaurs like Pteranodon whose wing was like a small plane.

The lack of good pterosaur examples from this time period has hindered scientists’ efforts to understand how pterosaurs evolved from these earlier forms to those that dominated the skies later in Earth’s history. Ceoptera This helps fill a gap.

For the past 15 years scientists have studied transitional pterosaurs that show a combination of features seen in the earlier tail forms and their later giant relatives. Ceoptera one of these transitional forms (called Darwinopteran), one of the first members of this group known from Europe, and is the second oldest darwinopteran in the world.

It does this Ceoptera crucial to understanding the pace of pterosaur evolution, and put the appearance of more advanced pterosaurs back to the Early Jurassic period, about 10 million years earlier than previously thought. It brings us one step closer to understanding where and when the more advanced pterosaurs evolved.

CeopteraThe discovery shows how palaeontologists are making new discoveries all the time, even in places like the UK – one of the most surveyed places in the world. It also shows how new technology can help uncover the Earth’s ancient mysteries.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a curated selection of the latest releases, live events and shows, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Register here.

This article from The Conversation is republished under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Paul Barrett is affiliated with the Linnean Society (Trustee).

Elizabeth Martin-Silverstone does not work for, consult with, hold shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and she has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond her academic appointment.