-

During World War II, scientists experimented on themselves to help divers and submarine crews.

-

The scientists performed more than 600 experiments on themselves, breathing CO2, oxygen, and more gases.

-

The British Admiralty used their data for repeat missions, including before D-Day.

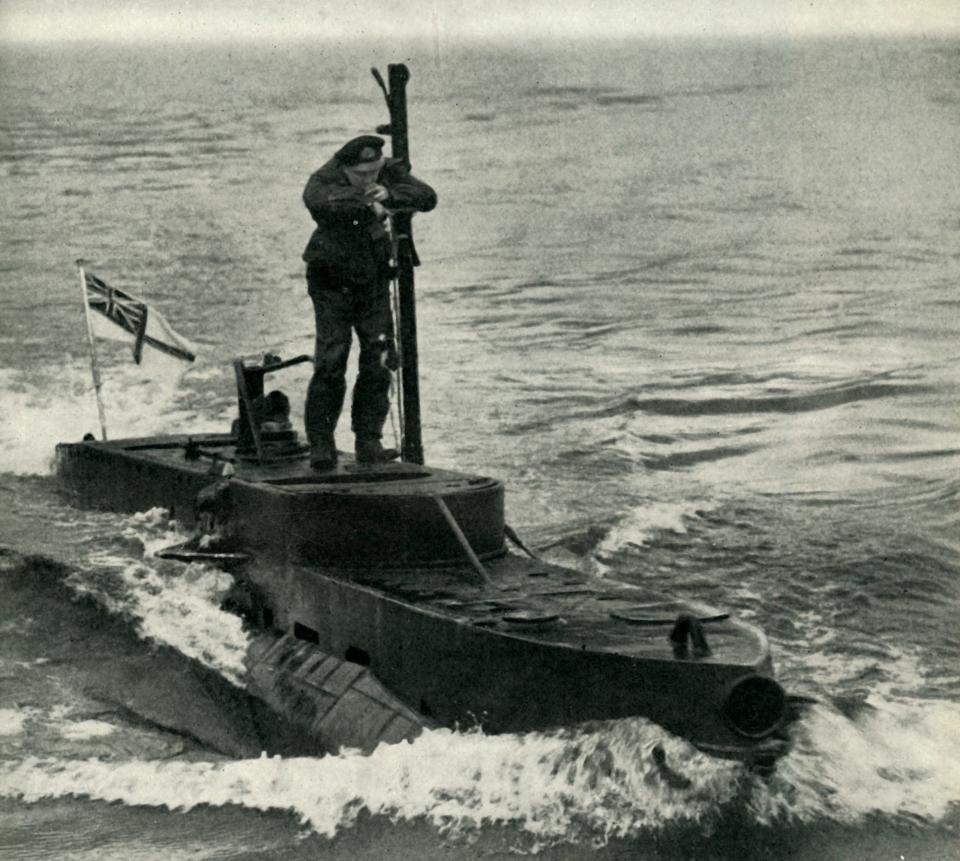

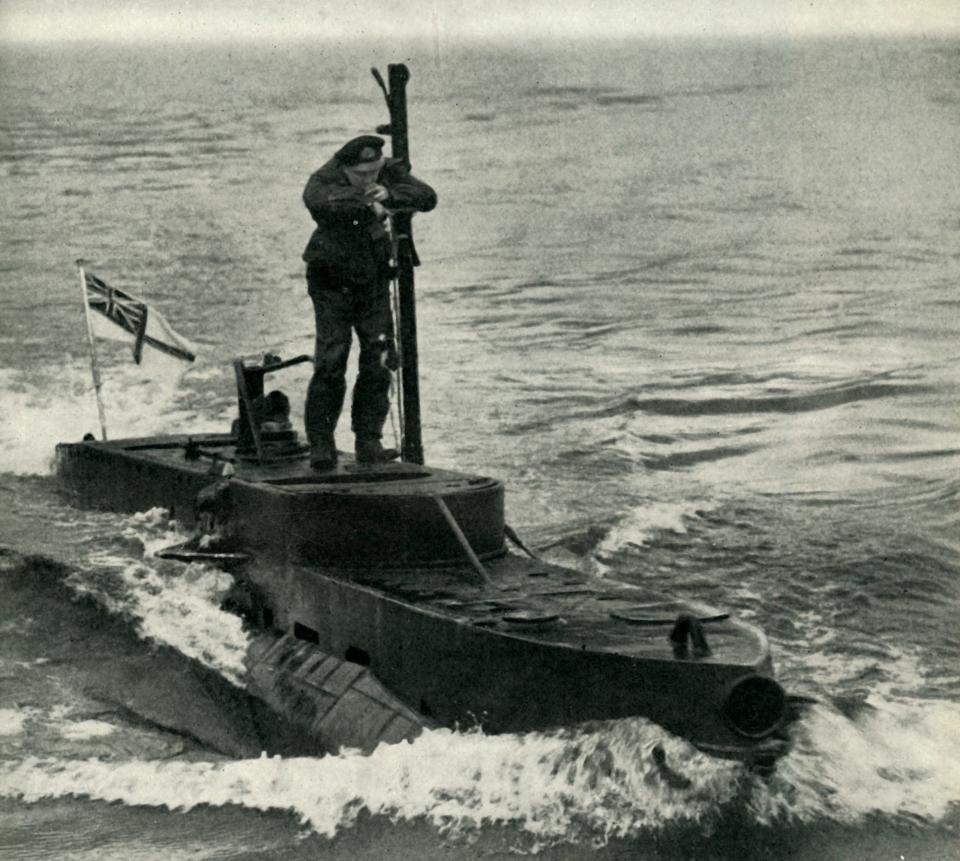

On January 18, 1944, a small submarine known as an X-vessel made its way from the English Channel to French waters undetected. For four nights, the subsurface came every 12 hours to let in fresh air.

The submarines were on a reconnaissance mission. Two British Army officers aboard the sub swam ashore to mark landmarks and dug mines recently, gathering intelligence for the troops who would invade the Normandy beaches on D-Day, five months after after that.

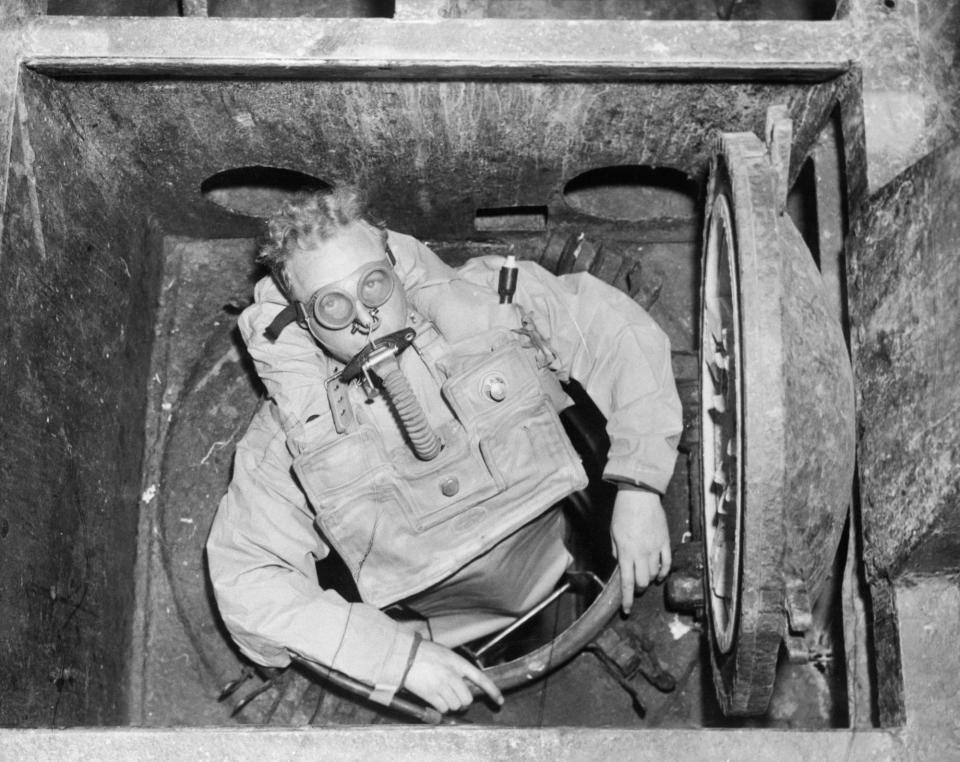

The small group of scientists aboard the sub conducted hundreds of experiments on themselves to find out how long the X-craft could stay underwater with the occupants breathing their own expelled carbon dioxide.

They locked themselves in hyperbaric chambers, where they breathed carbon dioxide, pure oxygen, and other gases to learn how best to breathe underwater.

These scientists carefully documented the dangers of breathing regular air and pure oxygen at different depths – helping to pave the way for modern divers, who often use different gas mixtures depending on how deep and they are going.

In her new book, “Chamber Divers: The Untold Story of the D-Day Scientists Who Changed Special Operations Forever,” Rachel Lance tells the story of the many injuries and near-death experiences the researchers endured, from a broken spine to fall lung.

The British Admiralty, which commanded the Royal Navy, used the scientists’ data to help the troops pilot small submarines, dismantle underwater obstacles, and carry out other reconnaissance missions. All these tasks were vital to the D-Day mission.

The many dangers of diving

By the 1940s, diving was popular but required a heavy suit and large helmets. Anyone going underwater for long periods needed a cable to attach them to a boat and provide a constant supply of air.

Experts have already known about the dangers of decompression sickness, also known as the bends, for many years. When a diver surfaces too quickly after a deep dive, nitrogen bubbles can flood the bloodstream due to the pressure change. The formation of bubbles blocks blood flow and, in the most serious cases, can lead to death.

But that was not the only concern of the British Admiralty regarding underwater travel. In 1939, the submarine Thetis sank during a diving test. Although four escaped, the other 99 trapped on board died of causes unknown at the time. Having breathing apparatus on board was not enough to save them.

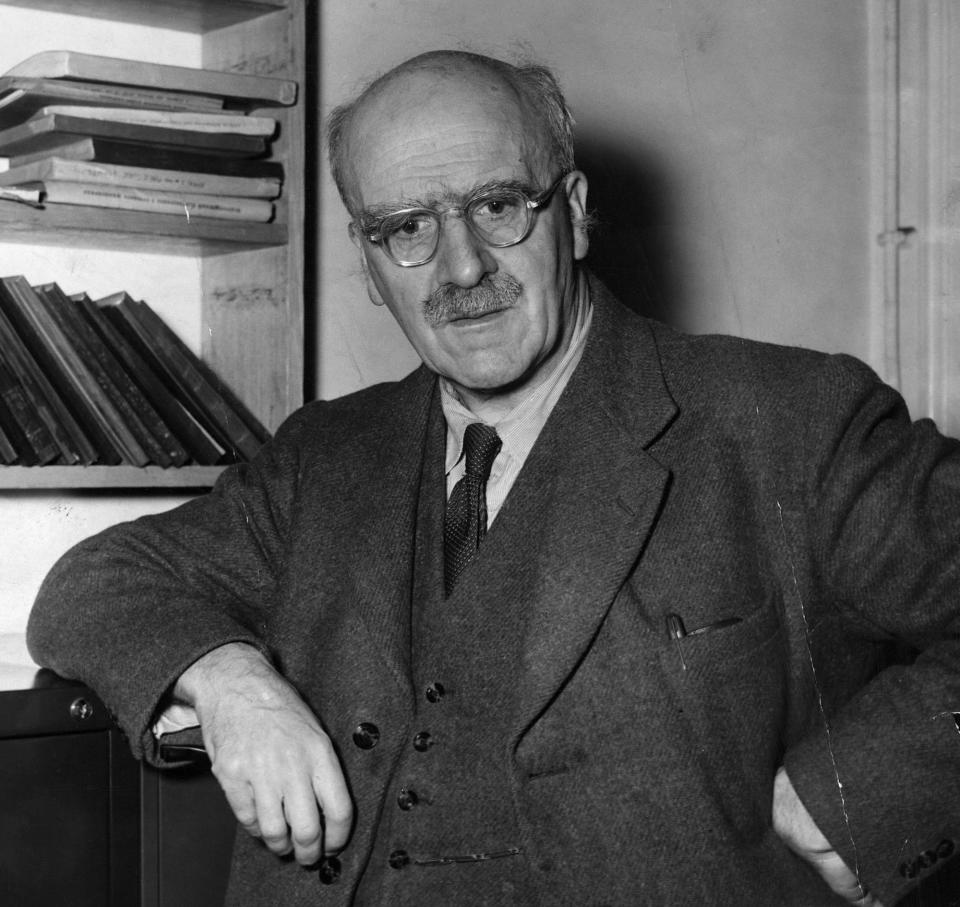

An engineer investigating the disaster asked for help from John Burdon Sanderson Haldane, who worked in the genetics department at University College London, to find out what happened. Haldane participated in his physiologist father’s experiments on decompression sickness and breathing various gases in his laboratory at home since he was a child.

Haldane and a handful of fellows from his laboratory quickly set to work conducting experiments in hyperbaric chambers. They were the guinea pigs.

Pure oxygen can be poisonous

Haldane and his fellow scientists looked at different levels of carbon dioxide and oxygen to see how their bodies responded at different levels of pressure. CO2 would give them headaches, make them tired, and make them hyperventilate.

It was the excess CO2 that killed those aboard the Thetis, Haldane realized, and future crews would need a way to absorb the gas.

Pure oxygen could be just as poisonous. It caused violent seizures, vomiting and impaired vision. The researchers would see flashes of color they called “dazzle.” Haldane injured his back during a seizure, and another researcher dislocated his jaw.

The seizures were bad enough in a dry hyperbaric chamber, but one of the researchers almost breathed oxygen and drowned in the water.

During the researchers’ tests, breathing regular air – which is mostly nitrogen – at increased pressure caused a phenomenon known as nitrogen narcotics.

It was strong enough that “no great confidence should be placed in human intelligence under these circumstances,” wrote Haldane and Martin Case, another researcher. Although the phenomenon was not new, the fact that scientists were struggling to do math problems under its effect showed that it could be fatal for divers trying to do simple tasks.

Finally, the researchers began mixing oxygen and air to find an ideal composition that would allow divers and submarine crews to breathe without side effects such as seizures or vision loss.

Haldane and other members of his laboratory performed a total of over 600 experiments on themselves. The British Admiralty used their data when equipping its X-craft submarines and giving out customized mixtures of oxygen and air based on the depth of their dives.

The documents chronicling the work of Haldane and his fellow scientists were declassified in 2001, well after many of them had died. Not only did their dangerous experiments contribute to the D-Day invasion, but they contributed to the science behind scuba diving today.

Read the original article on Business Insider