-

NASA’s TIMED satellite narrowly avoided a collision with the dead Russian Cosmos 2221 spacecraft this week.

-

In a worst-case scenario, the collision would send 7,500 bits of debris into low-Earth orbit.

-

Satellite collisions are becoming more likely as the amount of space junk in low-Earth orbit increases.

Two satellites in space nearly collided Wednesday in a terrifying encounter that LeoLabs, a satellite tracking company, called “too close for comfort.”

NASA’s Energy and Dynamics and Ionospheric Thermal Energy and Dynamics (TIMED) satellite passed by Russia’s defunct Cosmos 2221 spacecraft less than 65 feet. That’s shorter than the length of a tennis court.

Both of these satellites are non-portable, meaning neither the US nor Russia have control over where they go.

If they collided, it could destroy both satellites, blasting 2,500 to 7,500 pieces of space junk into Earth’s orbit that would now be zooming around our planet at thousands of miles an hour, faster than bullets .

The fragments would not be a danger to life on Earth, as anyone who entered our atmosphere would have burned up during free fall.

But the life of the space flight and the astronauts would be in danger because of the debris that could be in low Earth orbit much more treacherous.

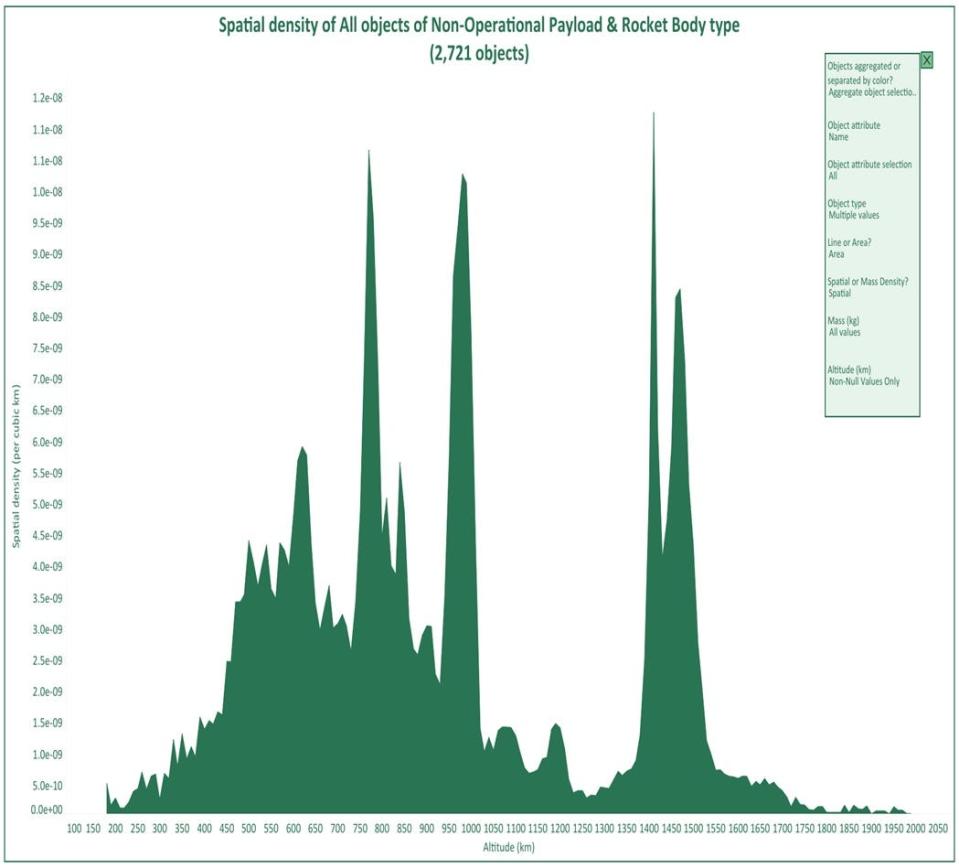

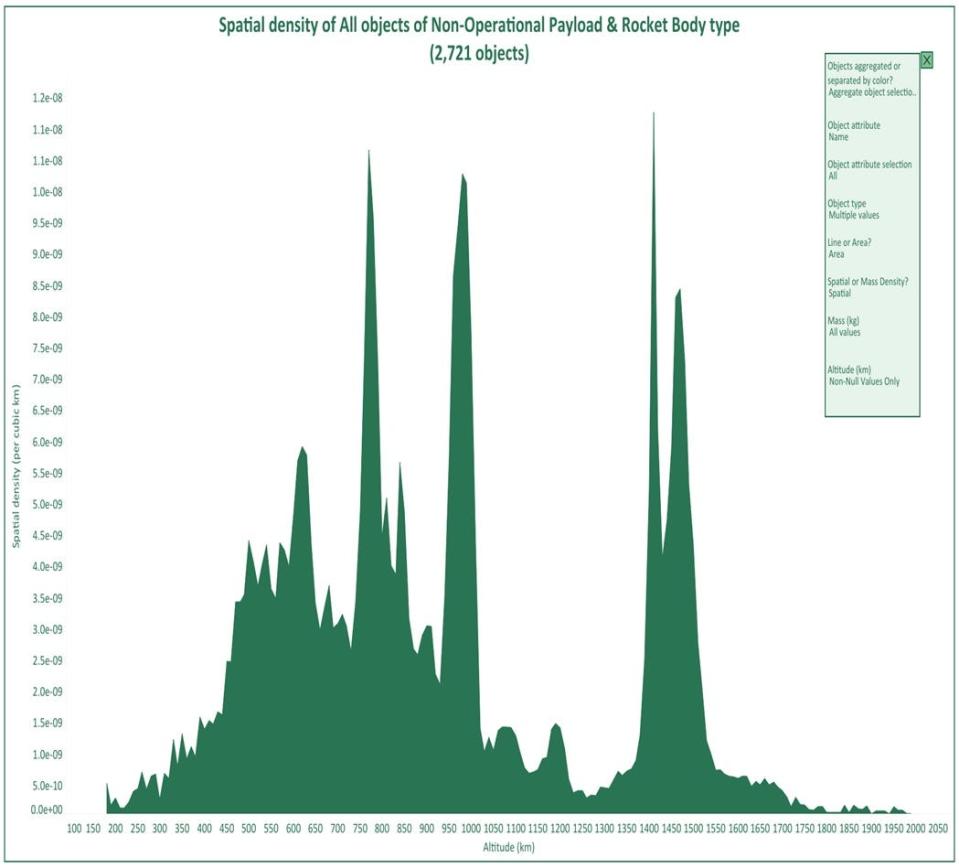

“There are ‘bad neighborhoods’ where these massive derelicts are preferentially piling up,” LeoLabs Senior Technical Fellow Darren McKnight told Business Insider in an email.

Avoiding collisions in these crowded areas is becoming increasingly difficult as the number of objects in Earth’s orbit increases each year.

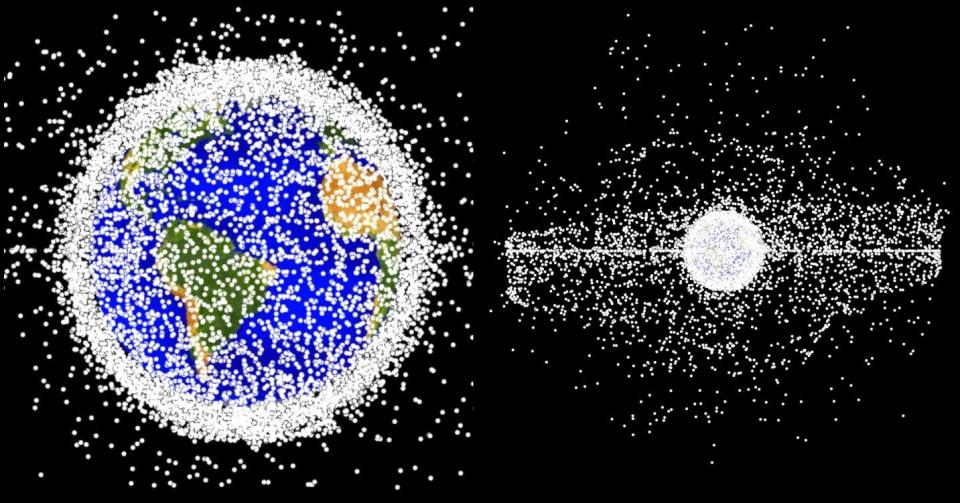

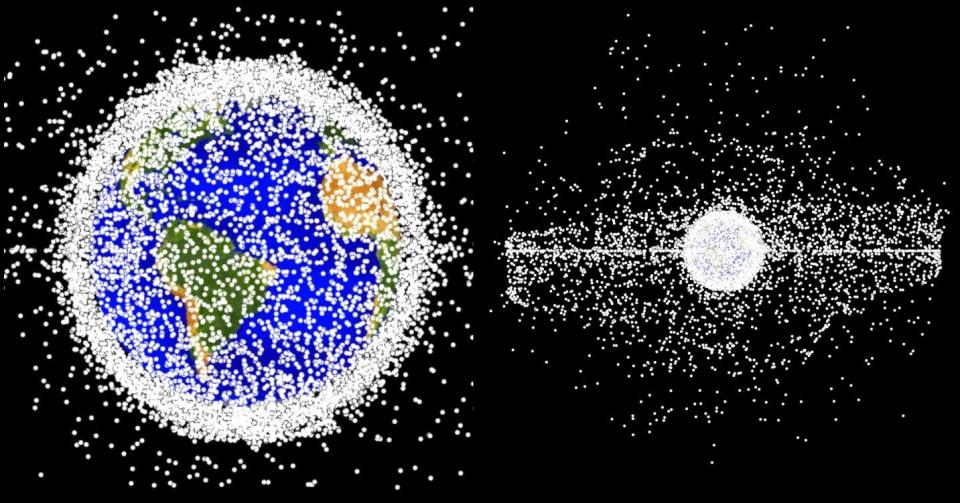

Earth’s orbit is getting crowded

Near-collisions between large space objects like this are rare, but it only takes one to completely change the landscape of Earth’s orbit and endanger countless other satellites, space telescopes, and even the International Space Station.

For example, two satellite collisions that occurred in 2007 and 2009, respectively, increased the amount of large debris in low-Earth orbit by about 70%.

And with the advent of mega-constellations of internet satellites, such as SpaceX’s Starlink and Amazon’s Kuiper, the number of objects in low-Earth orbit is increasing more and more every year, increasing the risk of collisions.

In 2007, scientists considered about 10,000 low-Earth objects. By 2021, that number had doubled. And most of it isn’t even useful – it’s space junk.

According to LeoLabs, about 70% is debris from damaged or abnormal rockets, satellites and non-operational payloads.

That’s just what’s cataloged, though.

The European Space Agency estimates that there are nearly 1 million bits of debris between 1 cm-10 cm orbiting the Earth, and another 130 million bits smaller than that.

Space junk is so pervasive that the International Space Station sometimes has to navigate around it.

In March 2023, the ISS dodged objects twice in one month, once to avoid a collision with a satellite and then again to shake off debris a few days later.

Even the smallest debris can damage the space station and endanger astronauts, although no astronaut has lost their life from space debris (yet).

The race to clean up space

The consequences of space debris are very real, so much so that the worst case has a name: Kessler syndrome.

In this case, a collision starts a chain reaction, generating a catastrophic domino effect that produces so much space debris, no spacecraft can safely leave Earth for hundreds or even thousands of years.

However, preventing collisions today can offset a case of Kessler syndrome in the future. And some governments and private companies have tackled the problem.

New space industry norms and even new policies in some countries are encouraging satellite operators to design their spacecraft to self-destruct when they die, by forcing themselves into a free fall that causes them to burn up in the atmosphere.

Last year the Federal Communications Commission – the US agency that regulates most communications satellites – took its first-ever enforcement action on space debris when it fined Dish Network $150,000 for failing to properly dispose of a retired satellite.

Some governments seem less concerned. India and Russia have tested anti-satellite missiles by destroying their own satellites in orbit, creating new clouds of debris.

For old, inoperable spacecraft roaming loose in orbit, like Cosmos 2221, NASA is outsourcing research and development to private companies to collect them.

In September 2023, the space agency awarded TransAstra $850,000 for their “Flytrap” space debris capture bag concept – basically, giant high-tech trash bags that would catch lots of junk.

Outside the United States, other companies are coming up with their own innovative disposal solutions. The Japanese company Astroscale has designed a spacecraft with a magnetic plate that can attach to dead satellites and drag them into free fall.

But these space-clearing technologies are still being tested. The European Space Agency plans to be the first to remove debris from Earth orbit with its Clearspace-1 mission, due to launch in 2026.

Meanwhile, LeoLabs hopes its precise data on objects in orbit will help satellite operators predict and avoid near-collisions like the one that happened Wednesday.

Read the original article on Business Insider