-

In the 1800s, expanding empires and seafaring explorations required food that was reliably preserved.

-

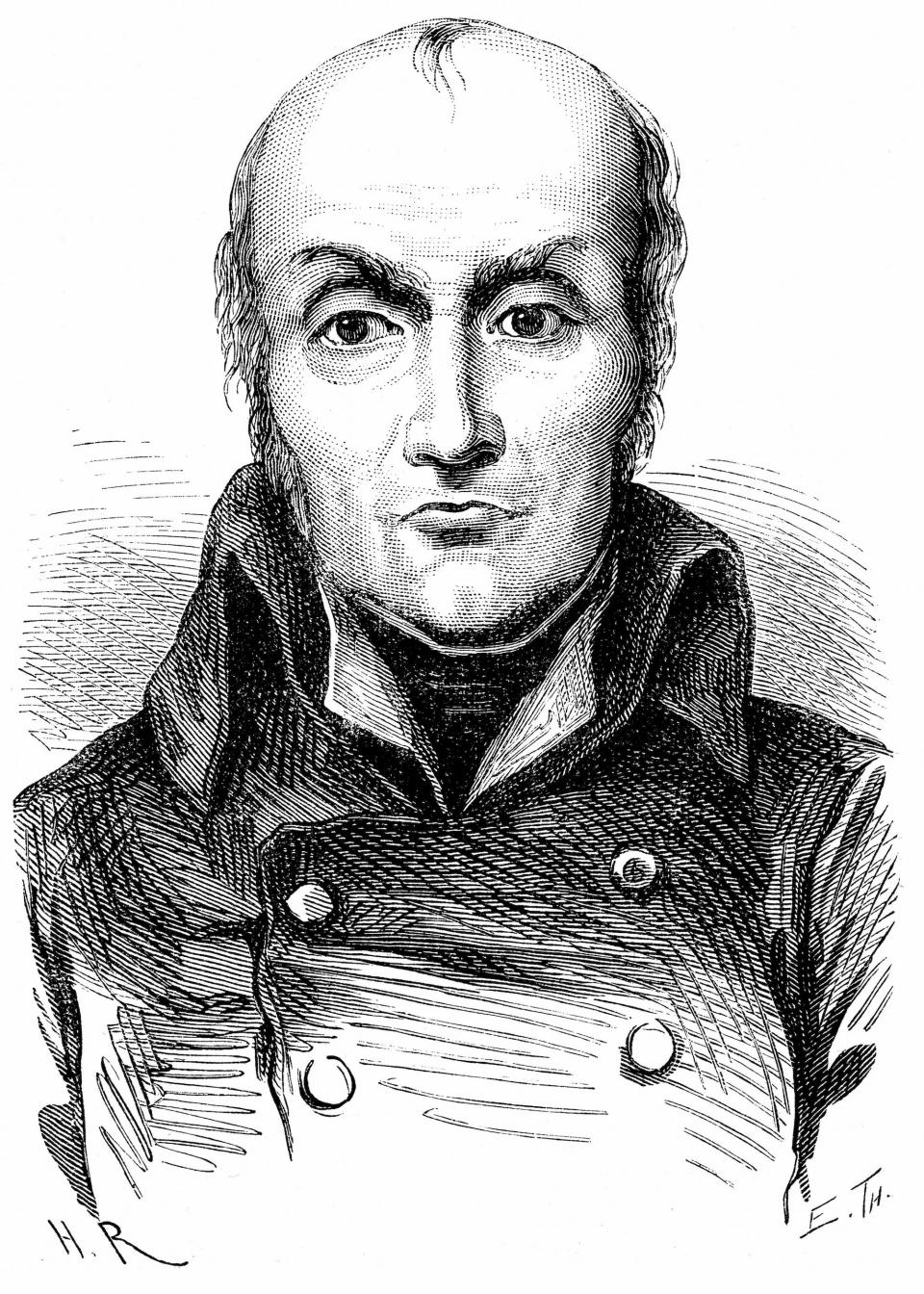

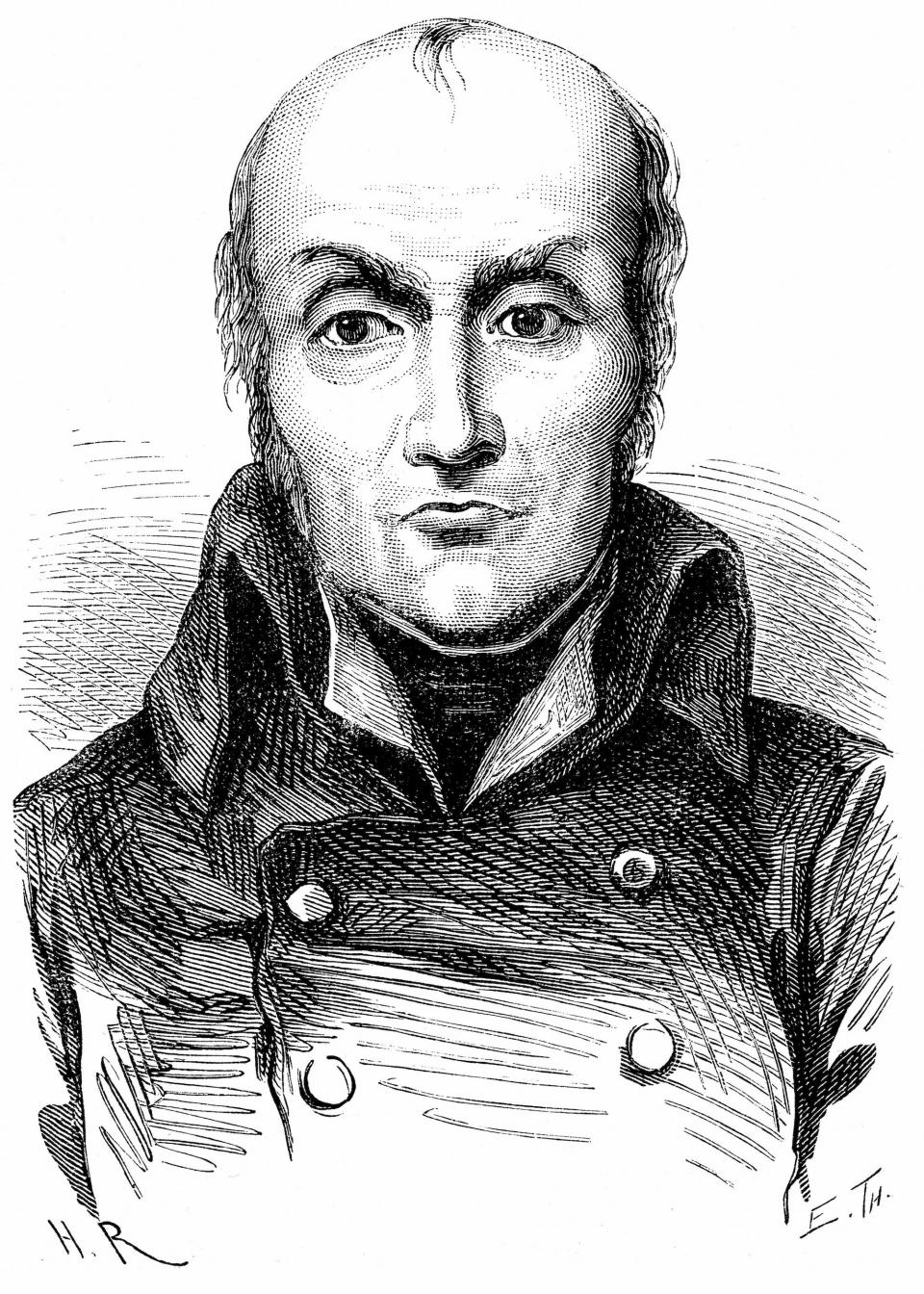

A candy maker was awarded 12,000 francs for his method of heating and sealing food in glass jars.

-

Bottles were heavy and fragile and were soon replaced by canned foods.

In 1815, the explorer and botanist Sir Joseph Banks wrote to a tinned food manufacturer saying that he had just eaten two-year-old tinned veal.

He called canned food “one of the most important inventions of the age in which we lived.” He also asked for a supply of concentrated consummé, because it was better than the soup he usually ate “at home or abroad.”

At the time, commercial tinned food was almost modern – almost on a par with Bank’s veal.

Finding a reliable method of preserving food was essential for colonized and warring nations. Among them was France’s Napoleon Bonaparte.

The search for ways to preserve food

Napoleon saw the effects of hunger and thirst as he led his army through southern Egypt in 1798.

When he came to power in France, Napoleon promoted doctors and scientists to positions of power to solve problems like this.

Those men then formed organizations and “supported research related to the preparation and preservation of food that could benefit the French army and navy,” writes historian Jennifer J. Davis in “Defining Culinary Authority.”

In 1809, one such organization, the Société d’encouragement pour l’industrie nationale, held a competition searching for methods of food preservation.

Nicolas Appert – who has been sealing food in corked jars for several years and has been experimenting with heating and bottling food for over ten years – accepted the award.

The Appert method of food preservation

Appert has been in the food industry almost since childhood. His father was an innkeeper and brewery owner, and worked in distilleries and wine cellars before opening his own patisserie.

The heating process required to make candy as well as the bottling process for wine and beer may have influenced his method of food preservation. He described himself as someone who was raised “in the art of preparation and preservation” and “lived, as it were, in breeches, breweries, storerooms, and champagne cellars.”

In 1795, he began trying to preserve different foods. He used empty champagne bottles, then specially made glass containers. After sealing them, he boiled the entire bottle and its contents in a water bath.

Appert wasn’t sure exactly why his method worked, but he believed that limiting his exposure to air and the heat of the water “were both absolutely necessary.” He was right on both counts.

In addition to bottling vegetables and fruits such as asparagus, cauliflower, peaches, and cherries, Appert also partially cooked some dishes before bottling and heating them. He made seasoned eel, mutton tongue, meat broth, and egg in bechamel sauce.

To ensure that his food retained the correct colour, aroma and taste, he tested different times and temperatures to heat different dishes. Many of them would probably fail food safety inspections, like the beef jelly that only needed to be heated for 15 minutes.

A day’s wages could be expensive for all welfare jars. For those who could afford it, they could open the can (which was really a chore until the can opener was invented decades later) and enjoy vegetables fresh green almost in the middle of winter.

Why didn’t Appert’s method catch on

In 1810, the French Ministry of the Interior paid Appert 12,000 francs to print a description of his conservation process “to spread the knowledge.” His book, “The Art of Preserving Animal and Vegetable Substances For Some years,” sold thousands of copies.

“Appert has found a way to fix the seasons,” according to one paper. Authors of elite cookbooks recommended his process.

Folklorist Danille Elise Christensen noted that the “water bath procedures without sugar” appeared in cookbooks written by women as early as the 1680s. Stories that focus on Appert and ignore Mary Mott, Sarah Martin, and others “valorize ‘scientific’ over and against ‘home’ knowledge,” Christensen wrote.

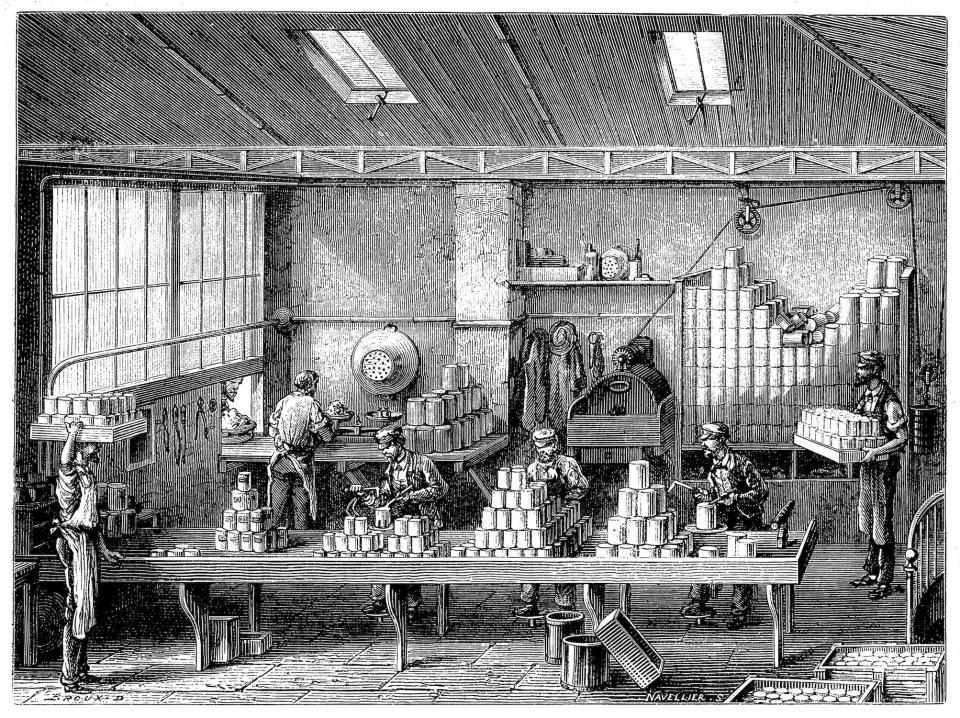

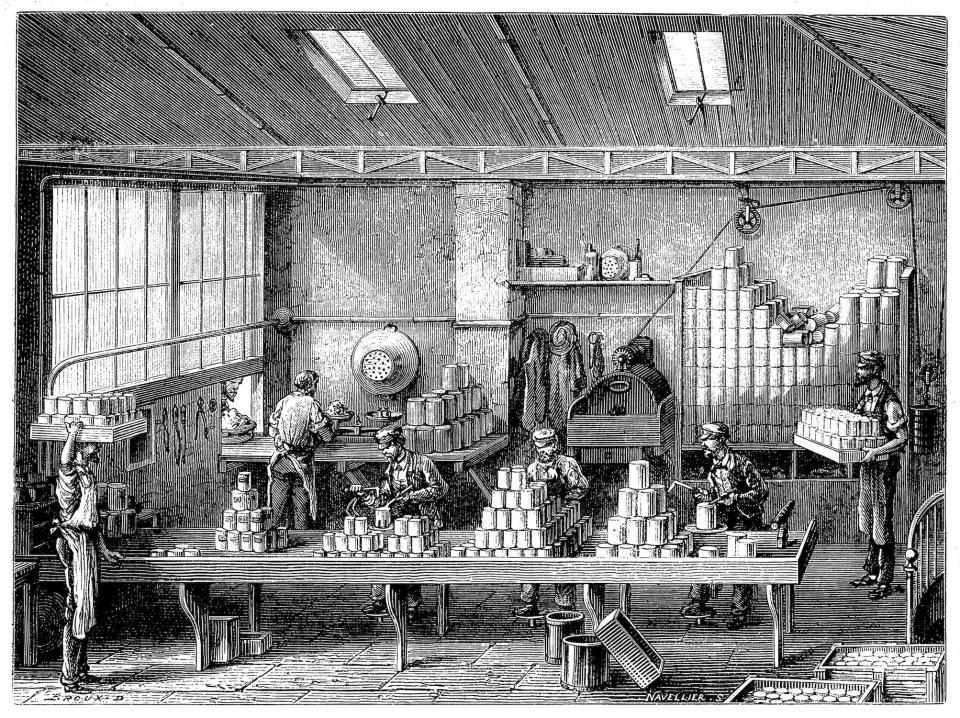

Appert was able to scale his technique, at one point employing fifty chefs to make his improvised dishes.

Other processes, including drying and the use of salt and sugar to preserve foods, followed after Appert published his book. His method was not “widely used on a scientific or industrial level” outside his own factory, according to Davis.

Although Appert’s cache had been tried by the French navy before he wrote his book, his fragile glass bottles were impractical for sea voyages. Within a few years, another French citizen, Philippe de Girard, went to London and patented his idea for a tin can through an intermediary.

From glass bottles to tin cans

Bryan Donkin bought the patent for £1,000, and it was he and his partners who enjoyed the Banks consummé. The cans could weigh as much as 20 pounds, but were heavier than Appert’s bottles.

The industry began to spread almost immediately. By the 1820s, the US had a few canneries, and the country’s first patent for tin cans was granted in 1825.

This was decades before Louis Pasteur developed his method of pasteurization and realized that bacteria were the cause of contamination. His technique significantly reduced the number of bacteria without completely sterilizing the food – that is, killing everything.

Botulism has been called “the disease of civilization.” Fatal outbreaks were caused by sausages and smoked ham. Improperly canned food can also tempt the bacteria.

It is one of the many reasons why commercially sold canned goods have waxed and waned in popularity in the centuries since Appert’s first experiments.

Despite his early success, Appert struggled with debt. When late in life he was under threat of expropriation, he wrote to the Ministry of the Interior, “I gave my life to science and humanity. You are taking the place I thought should be mine.”

Although he was evicted from his laboratory in 1824, the Reform government paid him 4,000 francs a year for ten years “in recognition of his service to the nation,” according to Davis.

Read the original article on Business Insider