Danny Sapani is the undisputed heavyweight of British acting. Although he has a fair share of TV credits, with notable roles in Killing Eve, the horror drama Penny Dreadful, and the sci-fi series Halo, he has yet to be cast in something that makes him a household name.

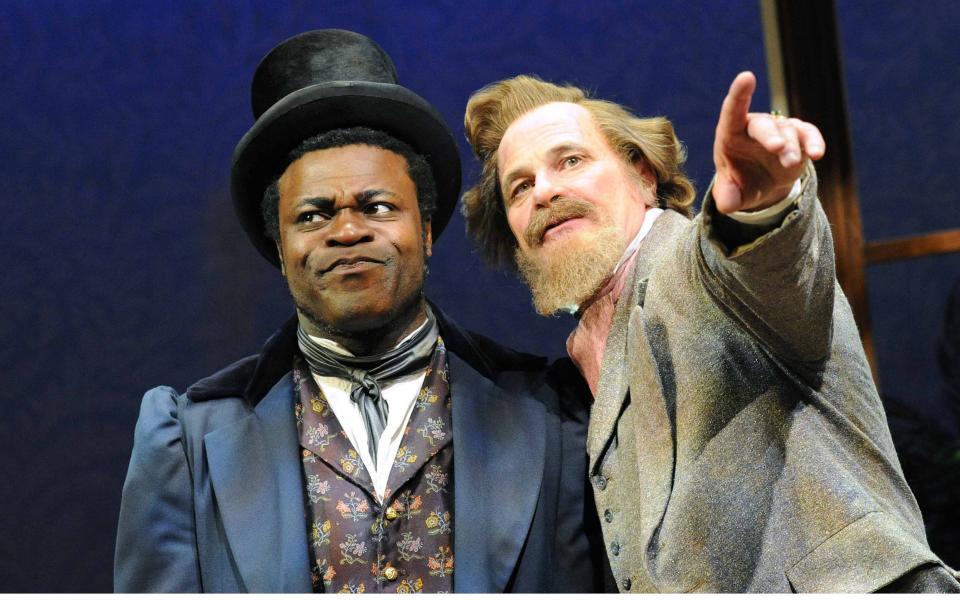

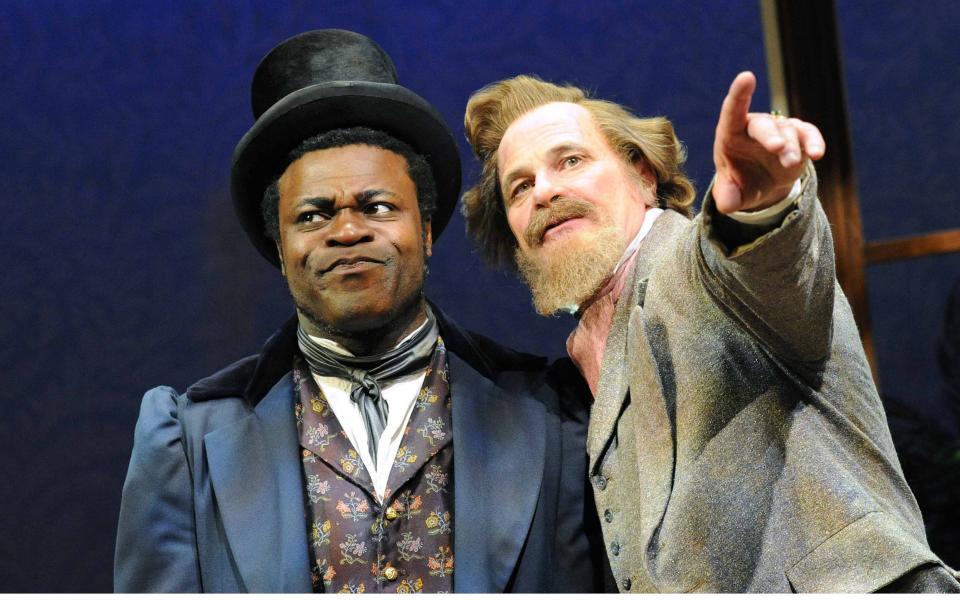

But even without small screen fans, his army of fans continues to grow, due to his exceptional stage work. In the last ten years, he has been forced as a conflicted, missionary-educated emigrants returning to Africa in Lorraine Hansberry’s Les Blancs, and riveted as the aloof, doomed Jason, opposite Helen McCrory, in Medea – both at the National. And he looked us up in the middle pandemonium alongside Adrian Lester in Lolita Chakrabarti’s Hymn, about male friendship, at the Almeida.

The team’s artistic director, Rupert Goold, is “an actor’s actor, with vital reserves of mystery and power”, referring to the way Sapani attracts unexpected attention. And he’s growing fast, too: “Some actors can become smaller or easier with age, but Danny has become deeper and more resonant.”

Now, the Almeida is the platform for Sapani’s biggest challenge to date, King Lear, directed by the South African visionary Yaël Farber, who provided a wonderfully atmospheric Macbeth there in 2021.

It is usually seen as part of Everest. Naughty? Sapani smiles as we meet early in the morning before rehearsals. “It’s so emotionally and physically hard, I’m not getting much sleep. I’ve gone from thinking ‘I’ll give it a try’, to ‘Oh, s–t, what have I done?’”

In a way, however, it is the result of a lifelong passion for Shakespeare, and Sapani has accumulated a lot of experience: playing Othello in Scotland when he was fresh out of drama school, Brutus in a Globe Julius Caesar (1999), and Macbeth in the acclaimed 2004 production Out of Joint set in a volatile African state. And much more besides. Her passion started early.

When he was about eight years old, growing up in Hackney, he would uncover his father’s material from Ghana, taking particular interest in one of the drawers under the drinks cabinet. “I’d reach in, like you do when you’re that age,” he explains, “and there were two books in that drawer – one was the Bible, and the other was Shakespeare’s Complete Works.” He looked at this brave new life: “I did not understand what I was reading, but it entered my consciousness.” Studying Romeo and Juliet for English literature at A-level confirmed the genius: “I thought ‘This is me, this is my life.’”

It is alarming, indeed shameful, that Sapani, 53, is in select company when it comes to Black Lears in the UK. The 19th-century African-American fan Ira Aldridge, who moved to England and toured the Continent, included Lear as part of his repertoire, but he hardly established a new template. Since the early 1990s, Ben Thomas has been there, standing in for Norman Beaton (of Channel 4 Desmond’s anniversary fame), the Talawa theater company in London, and Don Warrington (of Rising Damp fame, again for Talawa) at the Manchester. Royal Exchange. The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air’s Joseph Marcell came over to promote the 2014 outdoor Globe tour.

That’s an indictment, isn’t it? “Yes, it is,” he agrees. “We have a long way to go. It is sad to say that we in this country are caught up in all sorts of issues of color-blind solutions and color-visible solutions, and we still don’t have a solution to them. But we have an Asian Prime Minister and half the Cabinet is colored. So it feels right to tell the story in a modern style with a head of state of color.”

When I spoke to Derek Jacobi before his (Donmar) King Lear in 2010, he suggested that playing Hamlet was a very important rite of passage, allowing you to join the “classical club”, which ultimately confirmed your membership. with Lear. Hamlet says, according to Sapani, “he was not on the table” when he was young. It reminds me of Adrian Lester having to go to Paris, and work with Peter Brook, to get his chance at the role.

Farber (who also directed Sapani in Les Blancs) is clear: “We impoverish ourselves by imagining these roles as the exclusive domain of people who look special.” That said, her approach is to look at the universal aspect and psychological complexity of Lear’s tragedy, and race is not at the forefront. “It seems like a play about the unconscious,” says Sapani. “The play talks a lot about nothing – ‘nothing will come of nothing’ – and it seems that, at some deep level, Lear has decided to give everything away to find his true spiritual place. as a person, to understand his soul. .”

Sapani is married and has four children (two daughters, two sons, aged between seven and 23; and a half-sister aged 27). If there is a personal way into the role, it lies with his father, who was in the civil service in Ghana before moving to the UK, where he was a vintner (Sapani was the fourth of six children, and the first born ). here). He died in 2017. “I watched him decline from being a very powerful person to a shell of himself. The last thing he said to me was, ‘I’m sorry, I can’t talk right now, but thank you for coming.’ He was standing in his Y-fronts. It was as if that image was somehow prophetic about my playing Lear. this [performance] it is a tribute to his spirit and complexity, but especially to his weakness.”

It’s hard not to think about death even in your early 50s, he says. “When you hit 50 years old, it’s like walking down a sniper’s alley,” he jokes. “All kinds of health issues come into play. An impending mortality feels present.” He is still mourning the loss of Helen McCrory, aged 52, “We knew each other before Médé. We were close, and I think about her a lot doing this. Working with her was a highlight of my career. She was meticulous about every detail and changed the way I worked.”

Even in the cubby hole of a room at the Almeida, Sapani’s presence and warmth put you at ease, but also a little surprised. It is also fairly striking. He says: “Diversity is a word that is bandied around us and embraces anyone from a BAME background. But everyone has some kind of different story, even if they’re from Eton.”

As for the increasing prevalence of racial cross-casting, when I ask if it’s okay for a black actor to play, say, Churchill, he replies: “Yes. But by the same token, you should open the door for someone from a white background playing Kwame Nkrumah [the 1950s Ghanaian prime minister]. To be credible, you can’t do it one way, but not the other way.”

If he has any resentment for the breaks he didn’t get, he has no trace of anger. When I ask if he’s jealous of black actors coming into a more inclusive industry today, he shakes his head: “No, I’m excited. It’s a great time to be an actor. We’re in a place where there’s a lot more opportunity for everyone.” Future plans? “Well, I can sing and I’ve never done a musical,” he says. “But right now, I have this mountain to climb.” And who could argue with focusing on that?

‘King Lear’ runs from 8 February to 30 March at the Almeida, London N1; almeida.co.uk