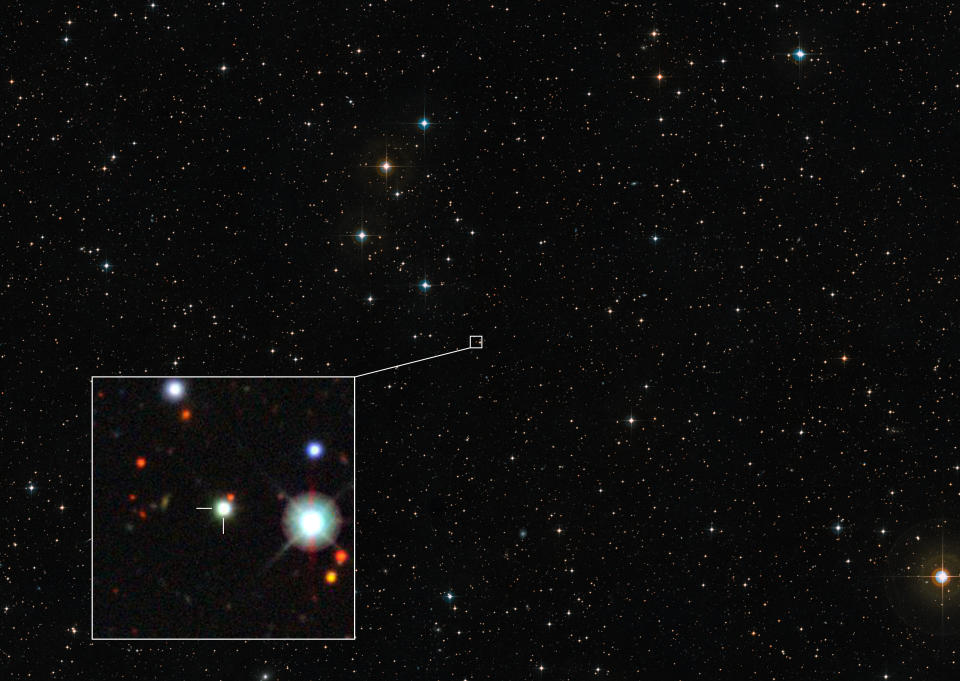

Newly discovered quasar is a real record breaker. Not only is it the brightest quasar ever seen, but it is the brightest astronomical object in general ever seen. It’s also powered by the hungriest and fastest-growing black hole ever seen – one that consumes the equivalent of more than the mass of one sun per day.

The quasar, J0529-4351, is so far from Earth that its light took 12 billion years to reach us, meaning it appears as it did when the universe was 13.8 billion years old just under 2 billion years age.

The supermassive black hole at the center of the quasar is estimated to be between 17 billion and 19 billion times the mass of the Sun; every year, it eats, or “acreates” the gas and dust equivalent to 370 solar masses. This makes J0529-4351 so luminous that it would be 500 trillion times brighter than our super star if placed near the sun.

“We have found the fastest growing black hole to date. It has a mass of 17 billion solar masses and eats directly above the sun per day,” team leader and Australian National University astronomer Christian Wolf said in a statement. msgstr “This is the most luminous object in the known universe.”

J0529-4351 was first seen in data more than 4 decades ago but was so bright that astronomers failed to recognize it as a quasar.

Related: The Event Horizon Telescope spies jets erupting from a nearby supermassive black hole

How a quasar has fascinated astronomers for 44 years

Quasars are regions at the core of galaxies that harbor supermassive black holes surrounded by the gas and dust that feed these voids. The violent conditions in the disks of matter around these active black holes, called accretion disks and generated by the massive gravity of the matter, heat the gas and dust and cause it to glow brightly.

In addition, any material in these discs not accreted by a black hole is sent to the poles of the cosmic titan, where it is blasted out as a jet of particles at the speed of light, which also generates powerful light. As a result, quasars in these Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) regions can shine brighter than the combined light of billions of stars in the galaxies around them.

But even among these very bright events, J0529-4351 stands out.

The J0529-4351 light comes from the massive accretion disk feeding the supermassive black hole, which the team estimates is about 7 light-years in diameter. That means crossing this accretion disk would be equivalent to traveling between the Earth and the sun about 45,000 times.

“It is surprising that it has remained unknown until today when we already know about a million smaller quasars. It has literally been staring us in the face until now,” said a team member and Australian National University scientist Christopher Onken said in the statement.

J0529-4351 was first spotted in the Schmidt Southern Sky Survey, which dates back to 1980, but it took decades to confirm that it was originally a quasar. Large astronomical surveys deliver so much data that astronomers need machine learning models to analyze it and sort quasars from other celestial objects.

These models are also trained using currently detected objects, which means they can miss candidates with exceptional properties like J0529-4351. In fact, this quasar is so bright that models have mistaken it for a star located relatively close to Earth.

This misclassification was seen in 2023, when astronomers realized that J0529-4351 was, in fact, a quasar, after viewing the region of the object using the 2.3-meter telescope at the Siding Spring Observatory in Australia.

The new discovery that this is actually the brightest quasar ever made when the X-shooter spectrograph instrument on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) followed J0529-4351 in the Atacama Desert region of Northern Chile.

RELATED STORIES:

— The supermassive black hole of the M87 galaxy spews jets at near-light speed

— Vampire black hole is ‘cosmic particle accelerator’ that could solve astronomy mystery

— The first ever imaged black hole has complex magnetic fields and scientists are thrilled

Astronomers are not done with J0529-4351 yet.

The team thinks that the supermassive black hole at the heart of this quasar is feeding close to the Eddington limit, or the radiation it emits should push gas and dust away, cutting off the black hole’s cosmic larder.

Further detailed investigation will be required to confirm this. Fortunately, however, the greedy supermassive black hole is the perfect target for the upgraded GRAVITY + instrument at the VLT, which will improve the high-contrast accuracy on bright objects.

J0529-4351 will also be investigated by the upcoming Very Large Telescope (ELT), currently under construction in the Atacama Desert.

However, the thrill of finding something new and exciting is what motivates the team leader behind this great discovery.

“Personally, I simply like the chase. For a few minutes a day, I feel like a child again, playing a treasure hunt, and now I bring everything to the table that I have learned since then,” said Wolf.

The team’s research was published on Monday (February 19) in the journal Nature Astronomy.