In a review published in the journal Communication Biology, researchers in the United States described the role and potential benefits of externally fermented foods in stimulating the expansion of the hominid brain. They further discussed the explanatory power of their “external fermentation hypothesis” and surveyed relevant food practices across human cultures.

Image Credit: Busker909 / Shutterstock

Background

Human brain volume tripled during evolution. Although brain enlargement has been studied in terms of its size and timelines, the mechanisms underlying this modification are not well understood. Various hypotheses have been proposed in this regard. The “expensive tissue hypothesis” suggests that the expansion of the human brain necessitated a redistribution of resources from the digestive system. This is evident in the fact that the human gastrointestinal tract is 60% smaller compared to primates. However, since the gut itself is responsible for absorbing nutrients, other studies have suggested that a larger brain size may support net fitness only if energy costs are adjusted through dietary changes, such as meat or tuber consumption to increase. Another potential dietary modification could be cooking, providing adequate calories and nutrition to support increased brain size and reduced gut size. However, the use of fire control would have required a fair level of cognitive ability, which could not have been present in hominins with a lower brain-to-body ratio.

Due to the limitations of the above hypotheses, there is still a gap in our understanding of the triggers of early encephalitis. Addressing this need, researchers in this review proposed the “external fermentation hypothesis” and discussed the evidence supporting it.

Internal fermentation

In the human gastrointestinal tract, particularly the colon, symbiotic bacteria break down organic food matter into nutrients such as short-chain fatty acids, a process known as internal fermentation. It provides additional energy from undigested fiber, improves the absorption of vitamins and minerals, and enables the breakdown of anti-nutritional factors (ANFs) present in food.

External fermentation and its role in brain expansion

On the other hand, external fermentation is when food is broken down by bacteria in the environment or on the surface of the food. External fermentation provides similar benefits as internal fermentation. It improves the health of the host’s gut by contributing to its microflora, improves nutrient absorption, improves the bioavailability of nutrients by breaking down ANFs, and helps convert poisonous substances into edible matter. In addition, external fermentation improves the host’s immunity as ingested probiotic bacteria colonize the gut and prevent the colonization of pathogens in the area.

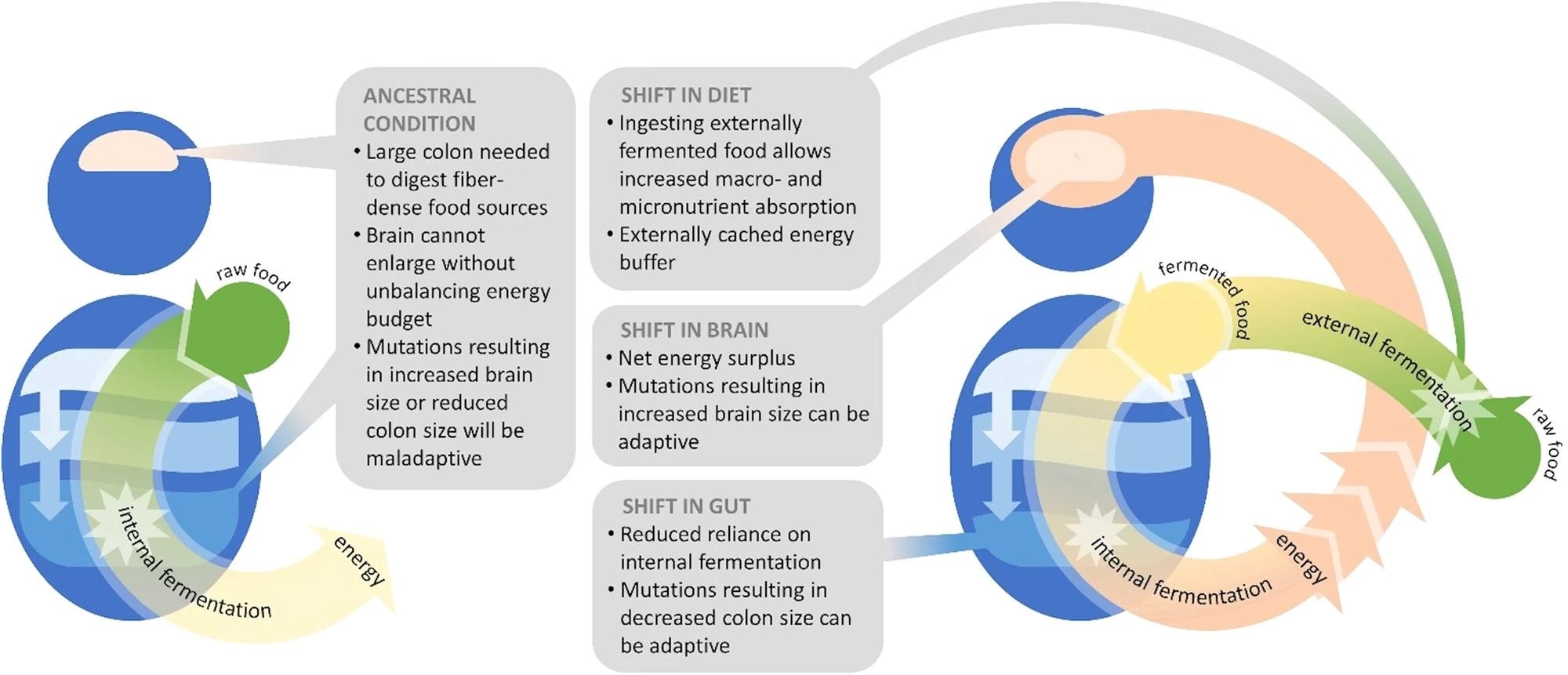

Diagrammatic representation of the External Fermentation Hypothesis.

Diagrammatic representation of the External Fermentation Hypothesis.

According to the researchers, the colon has shrunk by a significant 74% over evolution, indicating a reduced need to break down plant-derived food. The external fermentation hypothesis states that this change may be an adaptation after ingestion of externally fermented food.

The possibility of external fermentation was further debated, hypothesizing that early hominins may have been transporting and storing food, inadvertently initiating external fermentation. Over time, this practice may have evolved into a reinforced cultural phenomenon, contributing to brain expansion and cognitive development in hominins.

The explanatory advantages of the immediate hypothesis over others

Several explanatory advantages of the external fermentation hypothesis over previous hypotheses have been identified. Compared to dietary modifications such as tuber harvesting, meat eating, and cooking, eating externally fermented foods requires much lower cognitive capacity. Fermented foods offer all the benefits of cooked food and require no special planning, social coordination or attention. Fermentation seems more likely to be found than, for example, the fire required for cooking. Furthermore, fires need to be actively maintained, while fermentation is a passive process. Fermentation is a simpler alternative to other intensive food preservation techniques. The researchers suggest that hominins with lower cognitive abilities and smaller brains could achieve fermentation more easily than other methods.

Current fermentation practices

Today’s fermentation technology is highly developed and widespread. People around the world manage to ferment all kinds of food from different sources over different climatic conditions and time scales. The researchers compiled a list of examples and used them as evidence to support the plausibility, cultural acceptability and universality of fermentation.

Testing the hypothesis

To test the external fermentation hypothesis, the researchers propose different ways, including examining genetic changes related to metabolic, digestive and immune processes affected by external fermentation, analyzing olfactory receptor genes for potential positive selection associated with the detection of fermented food, and investigating changes in fermentation. human microbiome compared to monkey relatives. They emphasize the need for empirical research, including microbiological studies, comparative analyses, and genetic and genomic investigations, to support or reject their hypothesis.

Conclusion

The researchers in this review propose the “external fermentation hypothesis”, which suggests that the adoption of fermentation technology by early hominins was a key mechanism for the expansion of the human brain and reduction of the gut. They suggest that the conversion of gut fermentation to external practice may have been a significant innovation, setting the metabolic conditions for selecting brain expansion. This review provides new insights into the evolution of human diet and the anatomy of the gut and brain, seeking commentary and experimental trials to further validate the hypothesis.