Astronomers have discovered a quasar, powered by a supermassive black hole, in the infant Universe. Significantly, this quasar appears to be spewing molecular gas, the raw material needed to form new stars.

The discovery helps confirm theories about how star formation in some galaxies appears to have slowed to an almost complete end.

The quasar, known as J2054-0005, was spotted by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Northern Chile. We see it as it was about 12.8 billion years ago, when the universe was less than 1 billion years old.

Quasar, short for “quasi-stellar radio source,” is a name given to dense regions at the core of some active galaxies where a supermassive black hole overwhelms the feeding of surrounding matter and sends powerful jets of this matter to emit extremely bright light. to create.

Appearing as star-like point-like sources of light, when seen from far away quasars can be used to probe the conditions found in the early universe. Such regions have long been suspected of having a strong influence on the galaxies that surround them, but scientists say this is the first time we’ve seen hard evidence of suppression of star formation driven by outflows of molecular gas in the Universe. early, quasar-host. galaxy.

Related: The astronomers watch 18 ravenous black holes rip up and devour the stars

Stars form in massive clouds of molecular gas when a small region becomes too dense and collapses under its own gravity. This blob of pre-stellar gas continues to gather mass from the cloud, eventually becoming a protostar. The protostar continues to extract gas and grow until it is massive enough to fuel the nuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium at its core, the process that defines a full-fledged star.

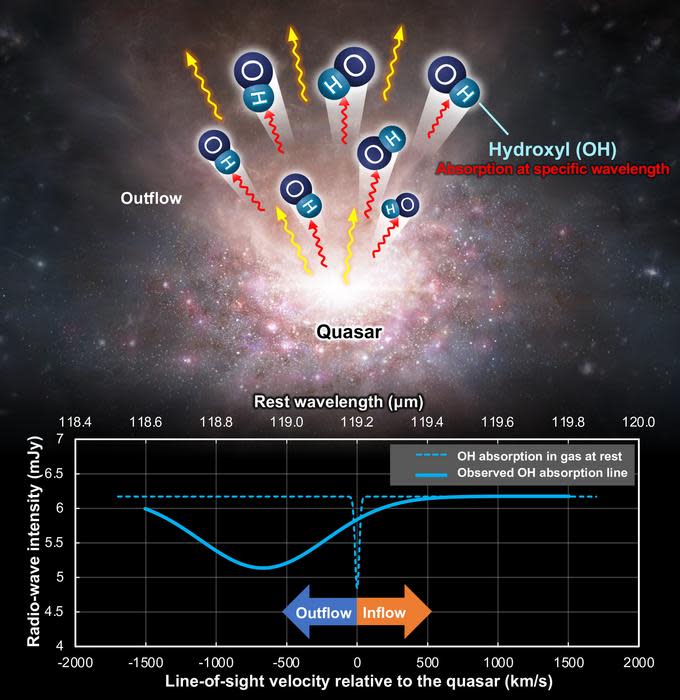

The richer a galaxy is in molecular gas, the more intensively it can give birth to stars with high concentrations, resulting in the production of large numbers of stars during so-called “starburst” periods. Conversely, if this gas is pushed out of a galaxy into interstellar space, faster than it can be consumed by the star formation process, these so-called molecular outflows suppress star formation.

“Theoretical work suggests that molecular gas outflows play an important role in the formation and evolution of galaxies from a very early age because they can regulate star formation,” said Dragan Salak, team co-leader and assistant professor at Hokkaido University, in a statement. “Quasars are particularly energetic sources, so we expected that they could generate powerful outflows.”

In the shadow of a quasar

J2054-0005 was chosen as the observational target to investigate these outflows and their consequences because it is one of the brightest quasars in the very distant universe, according to Takuya Hashimoto, co-director of the staff and assistant professor at the University of Tsukuba.

ALMA, meanwhile, which consists of 66 high-precision antennas comprising a single telescope, was chosen to observe J2054-0005 because the team believes it is the only telescope in the world with sufficient sensitivity and frequency coverage to out- detect the molecular gas flow of the targeted quasar.

The team detected the outflowing molecular gas through light absorption patterns, which means the researchers did not see the microwave radiation that comes directly from the bonded oxygen and hydrogen atom molecules, or “hydroxide” (OH) molecules that it contains. .

“Instead, we saw the radiation coming from the bright quasar – and absorption means that OH molecules happened to absorb some of the radiation from the quasar,” said Salak. “Thus, it was like revealing the presence of a gas by seeing the ‘shadow’ it cast in front of the light source.”

Related Stories:

— The black hole announces itself to astronomers by violently ripping stars apart

– Record breaker! Closest to Earth is the Uranus black hole

— NASA’s X-ray observatory reveals how black holes swallow stars and throw away matter

The team’s findings represent the first strong evidence of molecular outflows from quasars in the early universe, confirming how star formation slowed during cosmic infancy.

“Molecular gas is a very important ingredient of galaxies because it is the fuel for star formation,” Salak said.

The team’s research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal.