Astrobotic is still excited about the moon Falcon, despite the failure of the probe’s initial mission.

Peregine launched January 8 on the first flight of United Launch Alliance’s (ULA) new Vulcan Centaur rocket. Although the launch was successful, Hawk suffered a propulsion anomaly just hours into its mission that caused significant propellant leakage. It soon became clear that the Falcon would not reach the moon and would fall back to Earth, and the lander finally re-entered the atmosphere and broke up over the Pacific Ocean on Thursday (January 18). Astrobotic kept the community informed throughout the mission, posting updates multiple times a day on how the hapless lander was doing.

Despite the premature conclusion of the mission, Interstellar CEO John Thornton is proud of how well Peregrine performed. “I know it’s very easy to focus on the failure and the one thing that failed on the spacecraft, and we’re all going to dream about that for a long time,” Thornton said during a media teleconference on Friday ( Jan. 19).

“But many have worked,” continued Thornton. “And that’s something I’m very proud of. Astrobotic designed and built hardware like avionics and software architectures and systems and other parts of the spacecraft – they all worked.”

Related: Astrobotic loses contact with moon landing hawk

Thornton explained the Hawk anomaly, describing how a valve that separated the helium and oxidizer in the lander’s propulsion system did not reseal properly. This problem allowed a helium rush to enter the oxidation tank, raising the pressure to the point where the tank ruptured.

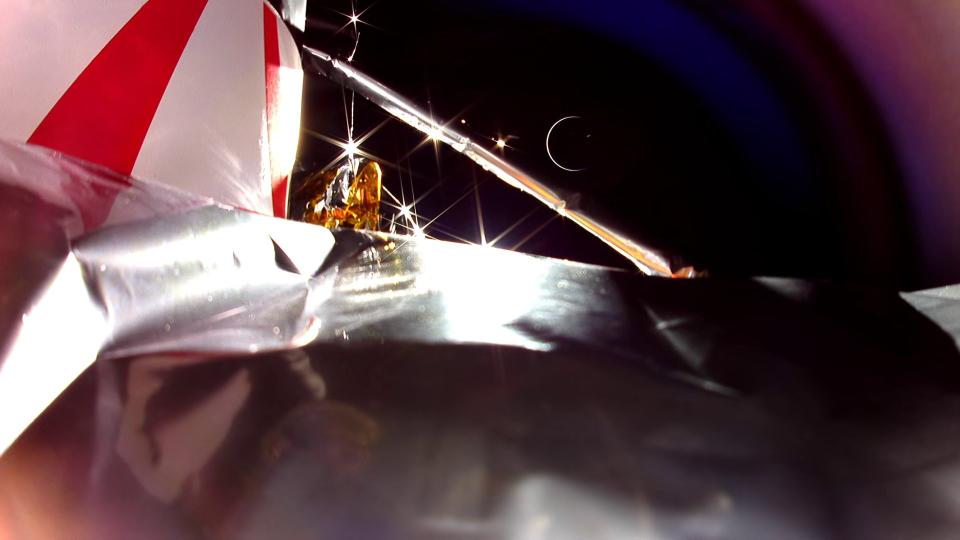

When the Astrobotic team realized what had happened, emotions immediately took over, Thornton said. However, this anomaly gave Astrobotic’s flight engineers incredible moments of ingenuity as they made improvised maneuvers to point the spacecraft’s solar panels towards the sun and even after taking a picture of Earth.

Thornton described how, to take the picture, Astronomy mission controllers had to turn the spacecraft so that a strut blocked the sun in the camera lens, likening it to using one finger to touch the sun. block out the person’s field of vision.

“That was a big emotional moment,” Thornton said. “Because I think that represents the best part of Constellation.”

Thornton added that mission controllers were able to use the doomed lander’s propellant leak to help them set the craft on a safe re-entry over the Pacific Ocean. “And the last move was really smart, because the leak was at that point and they figured out that if we could turn the spacecraft, we could basically use the leak to our advantage because a small continuous driving maneuver that could push us. further out in the ocean.”

The decision to send the Hawk on their way to re-enter across the ocean was not made lightly. Thornton said the company weighed the benefits of trying to stay on the landing course, but ultimately it was too risky and had the potential to create dangerous space debris.

“Theoretically, we could have done it maybe around the Earth and could have come back out to the moon. At that point, it would be a blow it’s anybody’s guess what could have happened,” Thornton said during the teleconference. “Maybe we could have made an impact. Maybe we would have missed the moon. Maybe we would have had enough fuel to maybe get into lunar orbit.

“It’s really a hypothetical world. At that point, we just don’t really know what would have happened.”

Some of the Peregrine payload also performed admirably despite not reaching their destination. A radiation detector built by the German Aerospace Center (DLR) was able to collect 92 hours of data related to the radiation environment in cislunar space, and two instruments built with NASA, the Neutron Spectrometer System (NSS) and the Transfer Spectrometer Linear Energy (LETS). ), they were also able to measure this radiation during Peregrine’s flight.

But many of the payloads were unable to fulfill their intended uses at all, such as the on-board lunar rovers or the controversial memorial payload containing human remains. Dan Hendrickson, Astrobotic’s vice president of business development, thanked the payload crews for their support during the mission, noting that customers “all knew the challenges and risks that about the moon mission and how hard it really is” to put a spacecraft on the moon. .

“When they came to the table, they implicitly understood that, but we didn’t take any chances. And we explained and explained all those challenges and risks as they were,” Hendrickson said. “And to their credit, they still signed up.”

Peregrine was the first mission contracted by NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, which aims to accelerate lunar science by partnering with private companies such as Astrobotic to send scientific experiments to the moon.

RELATED STORIES:

— ULA’s Vulcan rocket launches private US lunar lander, 1st since Apollo, and human remains on first flight

— Intuitive Machines’ private lunar lander launches for January 2024

— The launch of the 1st Vulcan Centaur rocket looks amazing in these photos and videos

Joel Kearns, associate deputy administrator for exploration in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said that “failure is often part of the road to success” and that the agency remains committed to CLPS despite Peregrine’s fate. “We are taking a risk posture [in which] New companies will innovate, push the envelope, and we’ll learn and grow from every flight,” Kearns said during today’s briefing.

The next mission contracted under CLPS will be launched soon: The lander Nova-C has been built by the Houston company Intuitive Machines to be launched towards the moon on top of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket in mid-February.