Located in the Pyrenees mountains, La Molina is the oldest ski resort in Spain. It has the largest superpipe in the Pyrenees and its slopes have hosted high-profile events, from the Alpine Skiing World Cup to the World Snowboard Championships. But La Molina now faces an existential threat: a lack of snow.

As global temperatures rise, the resort, like many around the world, is forced to rely more on artificial snow.

But fake snow comes at a cost. It is water and energy intensive – a difficult combination anywhere but especially in a country grappling with long and severe droughts fueled by climate change.

That’s why La Molina will spend the next three years testing a new snowmaking technique that promises to be much less resource intensive, as well as being able to produce snow at warmer temperatures – increasingly important as some resorts approaching temperatures too hot to even fake. viable snow.

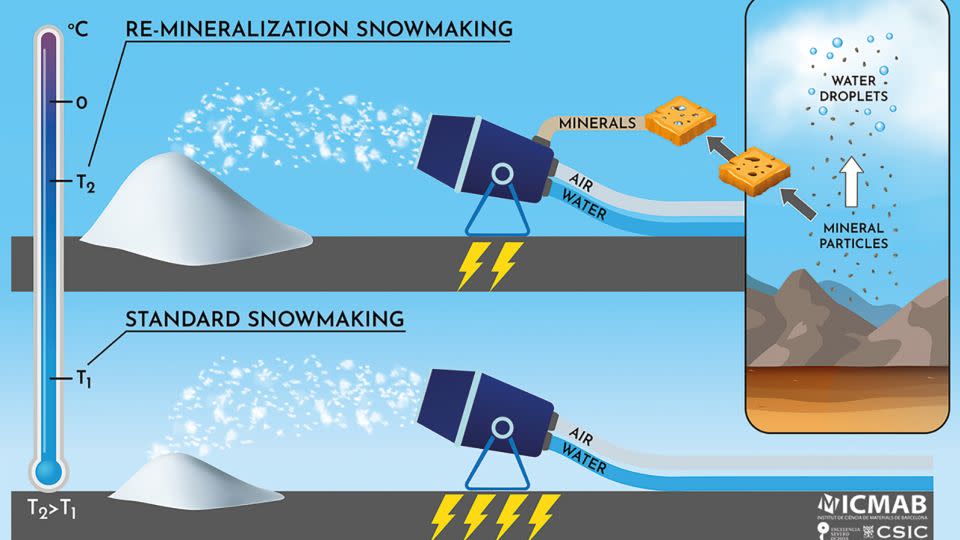

Called the Snow Laboratory, and run by the Barcelona Materials Science Institute (ICMAB-CSIC) and FGC Turisme, which manages public ski slopes, the project will make fake snow by adding a mineral to the water going into snow guns, the those machines. pumps out water and air at high pressure to create snow.

The idea is to imitate processes that occur in the clouds, said Albert Verdaguer, the scientist at ICMAB-CSIC who was in charge of the project.

Ice in the atmosphere is formed from water droplets in clouds through a process called “ice nucleation”. Pure water droplets can remain unfrozen in clouds at temperatures as low as minus 38 degrees Celsius. But ice nucleation can occur at much higher temperatures when the water droplets interact with particles in the atmosphere, such as aerosols or dust, causing them to freeze.

A few years ago, Verdaguer read a research paper that found that one mineral – feldspar – was extremely efficient at this process and could freeze water droplets at temperatures close to zero degree.

It set off a light bulb: What if felspar could help make snow more efficiently? “We thought, why don’t we take advantage of that?” he told CNN.

During laboratory tests, Verdaguer and his team found that the technique reduced energy costs by about 30% and was able to produce snow at temperatures about 1 to 1.5 degrees higher than traditional methods.

They were also able to get a better “conversion ratio,” Verdaguer said, referring to the volume of snow coming out of the guns in relation to the amount of water going in.

Usually, it’s about 75%, he said, because some water stays in the gun or it doesn’t freeze and it’s blown. The Snow Lab hopes to increase that to 90%.

About the size of a can of coke of feldspar — an abundant mineral that makes up about 60% of the Earth’s crust — would keep two snow guns going all season, Verdaguer said.

An industry at risk

Spain has been struggling with scorching heat waves and drought for years, and Catalonia, the region where La Molina is located, has been hit particularly hard. It is “one of the most severe droughts in recent years,” said Ramón Pascual Berghaenel, a meteorologist at the Spanish weather agency AEMET.

But La Molina is far from the only ski resort trying to carve out a future in a warmer and drier world. An unusually warm winter last year left ski resorts across Europe without snow, and this year, resorts in the Indian Himalayas were empty due to a lack of snow that kept tourists away.

“Obviously, there are shifts and changes from year to year, but the long-term trend (for snow) is decline,” said sports ecologist Madeleine Orr, who is not affiliated with the Snow Lab. Over the past four decades, human-caused global warming has reduced snowfall across much of the Northern Hemisphere, a recent study shows.

These changes mean that artificial snow, which has been used by resorts for many years, is gradually becoming a lifesaver. “The best estimates right now are that 95% of ski resorts depend to some degree on snowmaking to stay viable,” Orr told CNN.

But as temperatures rise, there are questions about how viable the snow will be in the future. When it is not cold enough, the machines will not work.

That’s why Snow Laboratory’s new technique is so attractive.

The science makes sense, said Jordy Hendrikx, chief snow scientist and chief scientific adviser for Antarctica New Zealand. “It’s a question of whether that can be scaled,” Hendrikx, who is not affiliated with the Snow Lab, told CNN.

That’s exactly what La Molina’s project aims to do – see if the lab results can be replicated in real life.

For the past few weeks, Verdaguer and colleagues have been setting up the snow guns at the resort. The water will come from a reservoir that fills with melted snow from the mountains in the spring and is not used for drinking water.

As well as testing the effectiveness of snowmaking, the project will carry out environmental tests to ensure there will be no adverse effects. Verdaguer is confident that it won’t, as feldspar is already widely used in the manufacture of glass, ceramics and paints.

“If this new technology is able to produce snow with less water, and without adding additional chemical agents … that could be a huge win,” Orr said.

But Hendrikx warned that even if the technique lives up to its promise, it may not be enough. As temperatures and humidity levels continue to rise, he said, “the improvement you have to make is going to have to be quite significant over what the natural environment is producing.”

More broadly, Hendrickx believes snowmaking is “maladaptation,” an attempt to adapt to climate change that could ultimately have adverse effects. “You are solving a problem locally, but you are increasing the problem globally through your energy use.”

Resorts could use green energy for fake snow, but as the world warms up, Hendrikx said, it could be argued that this clean energy could be better used elsewhere, “other than snow that make up a very small percentage of the population.”

And this hits a bigger problem: Declining snowpack is a problem far beyond the ski industry. “Snow is our water tower,” Hendrikx said, serving as a free store when people need it most. If it falls as rain, or melts earlier than normal, “we don’t have that much later in the spring and summer when we really need it.”

Hendrikx finds out why resorts make snow. Mountain economies depend on it. and Tourists have come to see snow as a resource that can satisfy their desire to ski or snow on powdery white slopes at certain times of the year.

Ultimately, resorts aren’t going to stop making snow anytime soon, he said, so “anyway we can find more efficient ways to do that, let’s go for it,” he said.

Over the next three years, Snow Laboratory will test its technique at La Molina but also eventually at two other ski resorts in the region to find out how well it works under different conditions.

The hope is that this technology will give struggling mountain communities that rely heavily on snow some breathing room, Vedaguer said.

“We don’t want all the ski resorts to be closed in five or 10 years, and we don’t have time to really think about something for the regional economy,” he said. “This is just to give us some time.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com