The ultraviolet universe is invisible from the Earth’s surface, and most of what we see comes from a single orbiting observatory that may retire in a few years.

The IS Hubble Space Telescope still in good health and may last until the 2030s, but is gradually being pulled back in The Earth’s Atmosphere. No spacecraft has been able to visit Hubble since 2009, two years before NASA retired its space shuttle fleet. There are early stage plans to Restore Hubble again, possibly using a SpaceX Dragon vehicle. But in the meantime, Hubble’s eventual retirement could leave a big void.

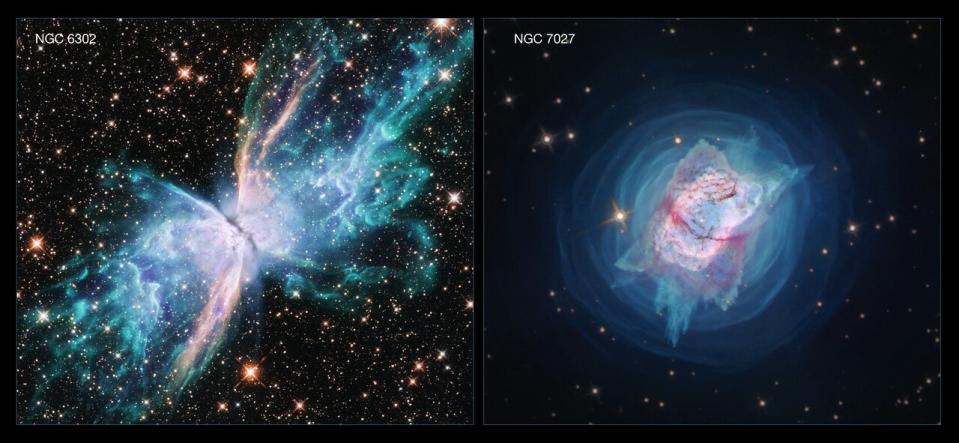

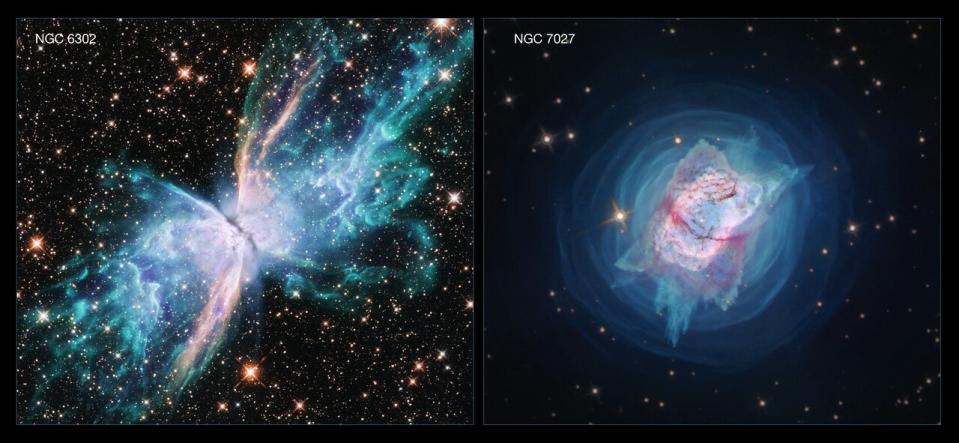

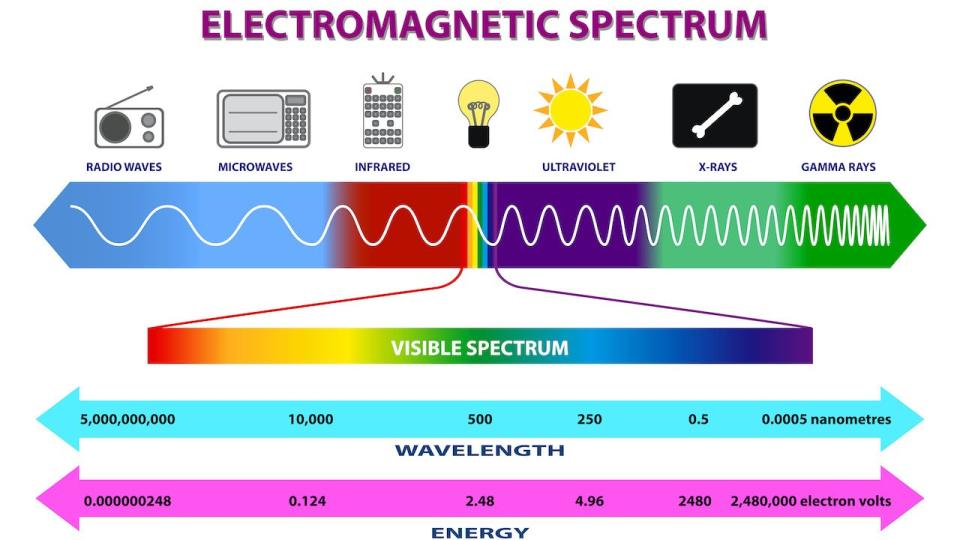

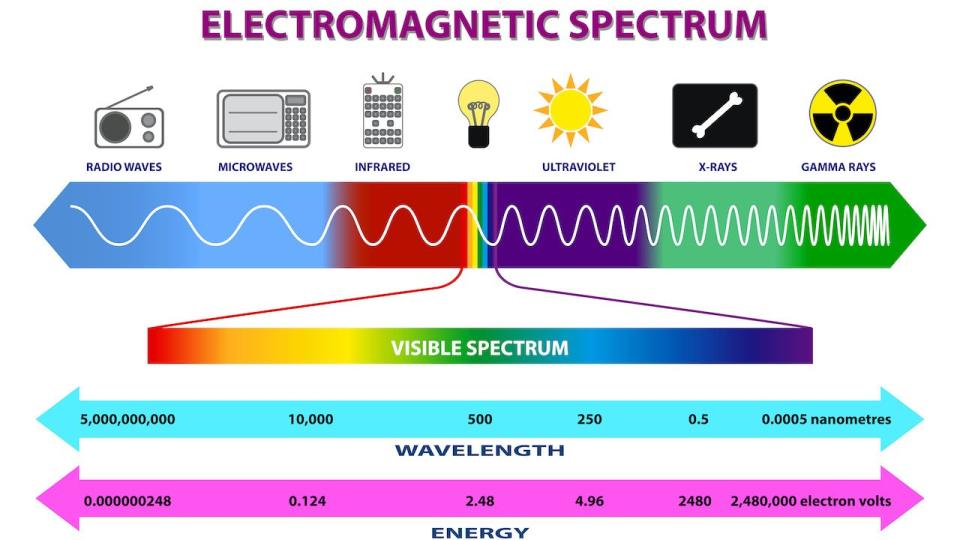

Hubble’s sharp eyes include ultraviolet vision. The Earth’s atmosphere blocks the most ultraviolet light, so it takes a space telescope to bring to light the young, hot stars that astronomers want to observe at those wavelengths — or are growing. black holesor deep explosions space. (There are other ultraviolet telescopes on spacecraft now, but they tend to be on limited missions that don’t reach the scope of the universe like Hubble does.)

So the time is now, claimed a team of 100 astronomers, to fund a new telescope to fly in 2029 with ultraviolet capabilities on board. The design is ready. The international and industrial partners are outlined. But what is needed is a commitment from the Canadian government to fund the next stages of the CASTOR telescope, which was considered a top priority by Canadians. astronomy communities in which final planning reportissued in December 2020.

“Hubble is almost 30 years old. It’s been a great workhorse, but it won’t last forever,” said CASTOR lead team member Sarah Gallagher, president of the Canadian Astronomical Society (CACSA) and an astrophysicist at the University of Western Ontario.

“We’re in a really beautiful position,” Gallagher told Space.com, “based on all the work we’ve done, and choosing to tailor the requirements so that it really fits this niche. that’s really exciting from a scientific point of view.”

Related: Jupiter’s Great Red Spot turns blue in new ultraviolet view from Hubble Telescope (photo)

CASTOR stands for Advanced Cosmological Survey Telescope for Optical and UV Research. The planned 3-foot-wide (1 meter) observatory is part of a new generation of telescopes that pack a lot of functionality into a small package. It would only cost something like $350 million USD ($480 million CAD) – almost equal to the average annual cost of Hubble, without the five space shuttle servicing missions. (The Hubble mission has cost a total of about $16 billion USD in constant dollars since its development began in 1977, according to NASA figures updated last month.)

Canadian astronomers want to lead the Earth-orbiting telescope, which is slated to fly about 500 miles (800 kilometers) high — twice the height of the International Space Station (ISS). Canada would contribute about 60% of the cost ($300 million CAD), with the balance coming from international partners. Large Canadian firms or branch companies like Honeywell, ABB, and Magellan are ready to start work when called upon to do so. United Kingdom Space Agency, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and space authorities in France, Spain and Israel want to contribute, with possibilities for a launch pad in India or South Korea.

But the funding decision is currently before the Canadian Parliament, which is devising the country’s 2024 budget to be released in the spring. An August pre-budget submission from the CASTOR team argues that the mission would cement “Canada’s global leadership in astronomy” and allow the nation to finally lead an international astronomy project for the first time, after decades of research and contributions with other processions. efforts. There is also a large research team: there are representatives from the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), the National Research Council of Canada, the Astronomical Society of Canada and many universities in that country alone.

Canada, incidentally, has a reputation for making smart space bets with limited tax dollars in a country that can only host 40 million people. The Canadarm robotic arm series has held the national astronaut seats since 1984; in 2023 alone, that pledge promised to fund CSA astronaut Jeremy Hansen to the moon on NASA’s Artemis 2 mission, along with CSA backup astronaut Jenni Gibbons. CSA member astronaut Josh Kutryk will also fly to the International Space Station in 2025.

Related: Canada enters space with new lunar and ISS astronaut missions

This year also saw a flurry of other space announcements. There are promises to update Canada’s shipping rules support commercial rocket efforts. Canada also gave a funding commitment to expand and renew the long established Radarsat World critical observation series for military and climate change observations. He even promised a “lunar utility vehicle” to support it The free Artemis program, lunar astronauts, while continuing to fund a mini-rover that would launch in 2026. (The rover’s science team is led by fellow Western University professor Gordon Osinski, who regularly teaches geology to NASA and CSA astronauts , with some spaceflyers. accompanying him on trips to remote places here on earth.)

Although CASTOR has a smaller mirror than Hubble, the detector will observe a much wider swath of sky in both optical and ultraviolet light. Seeing so much of the sky at once in ultraviolet, for example, will allow astronomers to focus on parts of it the universe that changes quickly: “Often those are very exciting things, like things exploding. We love cosmic explosions,” Gallagher said. Such outbursts could be quickly detected by powerful ground-based instruments such as gravitational wave probes LIGO to follow up on the discoveries.

In addition, by studying ultraviolet wavelengths on a broad scale, CASTOR complements two other wide-field missions astronomers are working on. The IS European Space Agencyand Euclid telescope launched in July into deep space, and is already providing images in optical and infrared light. And, in 2027, NASA‘ looking for infrared Nancy Grace’s Roman Space Telescope Euclid will follow that Lagrange Point 2. That’s a stable gravitational orbit a million miles (1.5 million km) away from us on the other side the sun.

Gallagher says if the three telescopes could work together in real time, before Euclid’s main mission expires in 2029, that would be ideal – although CASTOR could always follow up on Euclid’s work after the fact if necessary.

“What’s so beautiful about having CASTOR, plus Euclid, plus Roman, is that they’re all focusing on different parts, different colors, so having all three of them together is the best all of them, because you get a lot more information,” she said. . The ultraviolet view would provide additional information on the galaxy populations (old and young stars), or sources of quasar which are powered by black holes.

“What interests me, in particular, are these things that change over time,” Gallagher continued. “So if you go back, and you revisit them over and over again to see them get a little brighter … you can look at how that changes as a function of color. And that can tell you about the overall structure of the system feeding the black hole.”

Phase 0, the mission analysis and identification phase for the telescope, in July, and the CASTOR team is busy gathering support for their budget submission. Many Members of Parliament were consulted. Letters of support came in from 13 different university research vice-presidents, along with the Canadian Association of Physicists. Gallagher herself met with representatives from across Canada at the annual Space Borne conference this fall, which brings together many of the scientific, government and industry communities, to continue the funding talks.

RELATED STORIES:

— Hubble Space Telescope: Pictures, facts & history

— Canadian Space Agency: Canadarm, the Artemis 2 lunar mission and astronauts

— What is Nancy Grace’s Roman Space Telescope?

“This is a well-researched project. A lot of the technology risk is retired. The science case is just as exciting. That’s why we were able to get these partners on board,” Gallagher said. But she admitted that getting funding for it is not guaranteed.

“Everybody we’ve talked to, honestly, is pretty excited about it. But it’s a tough budget cycle, and we understand there’s a lot of important priorities as well. But I think this is really the kind of thing where for Canada to be a leader in an exciting and world-class mission. The potential to train and inspire the next generation in all different fields is tremendous.”