Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on exciting discoveries, scientific advances and more.

The Stonehenge Altar Stone, which is at the heart of the ancient monument in southern England, was probably transported more than 435 miles (700 kilometers) from what is now north-east Scotland nearly 5,000 years ago, according to new research.

The results of a new study, published on Wednesday in the journal Nature, overturn a century-old idea that the Altar Stone originated in present-day Britain. The Altar Stone, the largest of the blue stones used in the construction of Stonehenge, is a thick block weighing 13,227 pounds (6 metric tons) that sits in the center of the stone circle.

“This stone traveled an awfully long way – at least 700 km – and this is the longest recorded journey of any stone used in a monument at that time,” said study coauthor Nick Pearce, professor in the Department of of Geography and Earth Sciences at Aberystwyth University in Wales, in a statement.

The research directly addresses one of Stonehenge’s many mysteries and opens up new ways of understanding the past, including the links between Neolithic people who have left no written records, said authors of the study.

Construction on Stonehenge began as early as 3000 BC and took place over several phases, according to the researchers, and it is believed that the Altar Stone was placed within the central horseshoe during the second phase of construction around 2620 to 2480 BC.

The discovery of the origin of the stone suggests that ancient Britain and its citizens were much more advanced and were able to move huge stones, possibly by maritime means, the authors of the study wrote.

Unlocking ancient secrets

Substantial research has focused on the types of stone used to construct the iconic circle located in Wiltshire over the years, and previous analysis has shown that bluestones, a type of fine-grained sandstone, and siliceous sandstone blocks known as sarsens were used in the construction of the monument . The landmark is located on the southern edge of Salisbury Plain, which was inhabited as early as 5,000 to 6,000 years ago.

The sarsens came from the West Woods near Marlborough, which is about 15 miles (25 kilometers) away, and some of the bluestones came from the Preseli Hill area in west Wales, and are thought to be the first stones invited to the site. Researchers have categorized the Altar Stone with the blue stones, but its origins remain a mystery until now.

“Our discovery of the foundation of the Altar Stone shows a significant level of societal coordination during the Neolithic period and helps paint a fascinating picture of prehistoric Britain,” said study co-author Chris Kirkland, professor and head of the Mineral Systems Timescales Group at Curtin University. The Australian School of Earth and Planetary Sciences, in a statement.

“Transporting such a huge cargo overland from Scotland to the south of England would have been extremely challenging, suggesting that there was probably a sea shipping route along the British coast. This suggests long-distance trade networks and a higher level of societal organization than is widely understood in the Neolithic period in Britain.”

To better understand the origin of the Altar Stone, the researchers analyzed the age and chemistry of mineral grains from fragments of the stone itself.

The analysis showed the presence of zircon, apatite and rutile grains within the fragments. The zircon was dated between 1 billion and 2 billion years ago. But the apatite and rutile grains came between 458 million and 470 million years ago.

The team used the analysis of the ages of the mineral grains to create a “chemical fingerprint” that could be compared to sediments and rocks across Europe, said lead study author Anthony Clarke, a doctoral student from the Mineral Systems Timescales Group within the Curtin School. of Earth and Planetary Sciences. The grains best match a group of sedimentary rocks known as Old Red Sandstone found in the Orcadian Basin in north-east Scotland, which were completely different from stones found in Wales.

“The findings raise interesting questions, given the technological limitations of the Neolithic era, as to how such a massive stone was transported over vast distances around 2600 BC,” Clarke said.

The discovery was also personal for Clarke, who grew up in the Preseli Hills in Wales, the point of origin of some of the Stonehenge stones.

“I first visited Stonehenge when I was 1 year old and now at 25, I have returned from Australia to help with this scientific discovery – you could say I have come full circle at the a stone circle,” Clarke said.

But when it is determined that the Altar Stone now came from Scotland, many new questions arise.

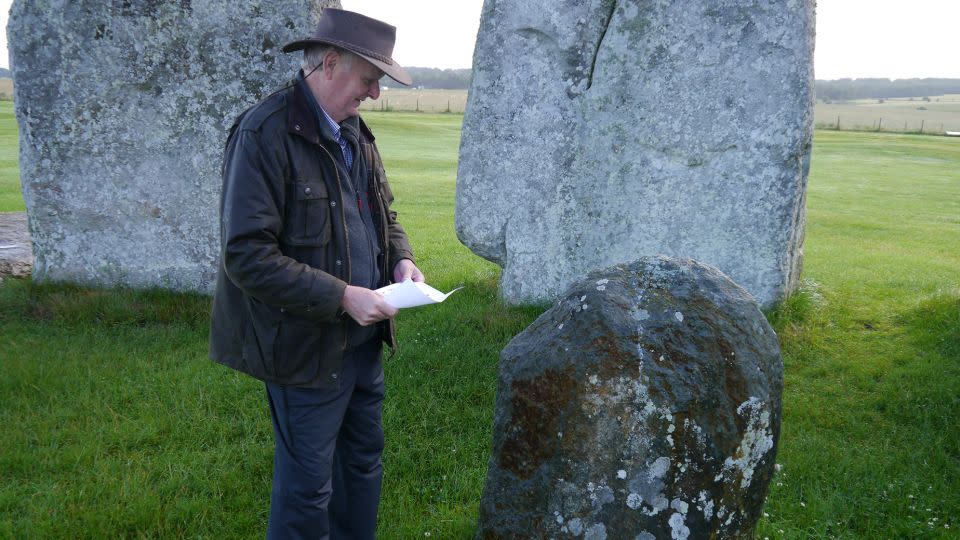

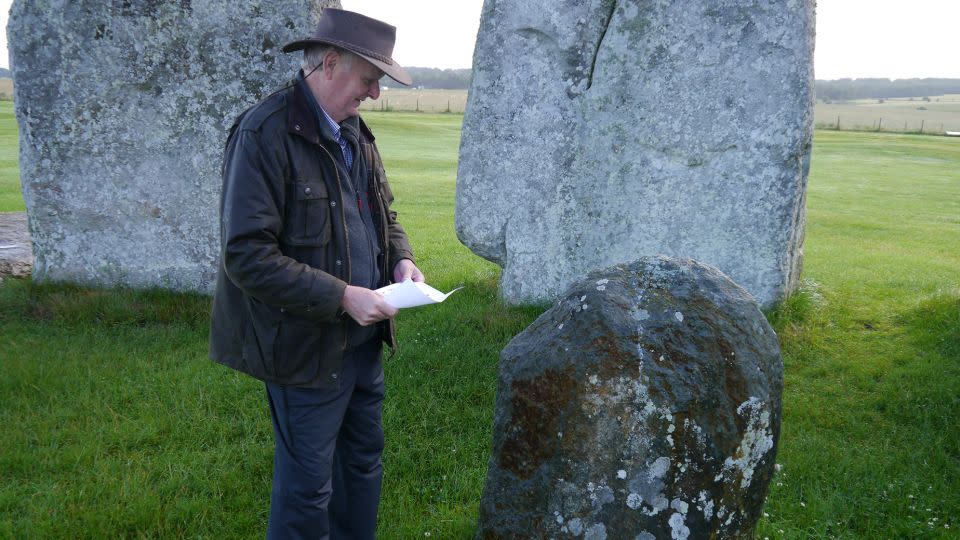

“It is very satisfying to know that our chemical analysis and dating work has finally solved this great mystery,” said study author Richard Bevins, professor emeritus in the Department of Geography and Earth Sciences at Aberystwyth University, in a statement. “The hunt will still be very much on to find out exactly where in north-east Scotland the Altar Stone came from.”

Joshua Pollard, professor of archeology at the University of Southampton, called the result “an amazing result”. Pollard was not involved in the research.

“The science is good,” Pollard said. “This is the team that was active in finding the small bluestones of Stonehenge using a battery of sophisticated techniques.”

Moving huge stones

Today, the Altar Stone is broken on the ground, with two stones from the fallen Great Trilithon structure lying on top of it. A trilithon is a pair of vertical stones with a horizontal stone lying across the top. The horseshoe shape of Stonehenge contains five trilithons, but the Great Trilithon was aligned with the solstice axis, so at the winter solstice, the sun appeared to be set between the two stones.

But researchers question whether the Altar Stone was once standing, as well as its purpose.

“One suggestion is that the stone is evidence of the dead, so the Neolithic people built stone circles as part of their rituals to honor their ancestors,” Bevins said.

Pollard referred to the Stone Altar as “an anomaly, located where the most sacred space within the monument should have been.”

But what exactly was the Altar Stone drive that reached Salisbury Plain in the first place?

At the time, Britain was covered in forests and other impassable geographical features that made it extremely difficult to transport the stone over land, the study authors said. But a sea route could be approved for sea transport, Clarke said.

“Incredible as it may seem, Stonehenge itself is an incredible monument,” Pollard said. “It looks more like the stones are drawn from sources ancestral to those who created Stonehenge – it consolidates the stories of historical lineages in one place.”

There are other examples of animals, objects and stones being transported that suggest that cargo could have been transported over open water during the Neolithic Period, the authors wrote in the study. Quarried stone tools have been found throughout Wales, Ireland and continental Europe, including a large stone grinding tool found in the county of Dorset which came from what is now central Normandy.

There is also evidence that shaped blocks of sandstone were carried on rivers in Britain and Ireland.

“Although the purpose of our new empirical research was not to answer the question of how it got there, there are clear physical barriers to transport on land, but a daunting journey by sea,” said Pearce. “There is no doubt that this Scottish source shows a high level of societal organization in the British Isles during the period. These findings will have huge ramifications for understanding Neolithic communities, their levels of connectivity and their transport systems.”

The authors agreed that some questions about Stonehenge may never be answered.

“We know why many ancient monuments were built, but the purpose of Stonehenge will always be unknown,” Clarke said. “And so we have to turn to the rocks. It is an enduring mystery.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com