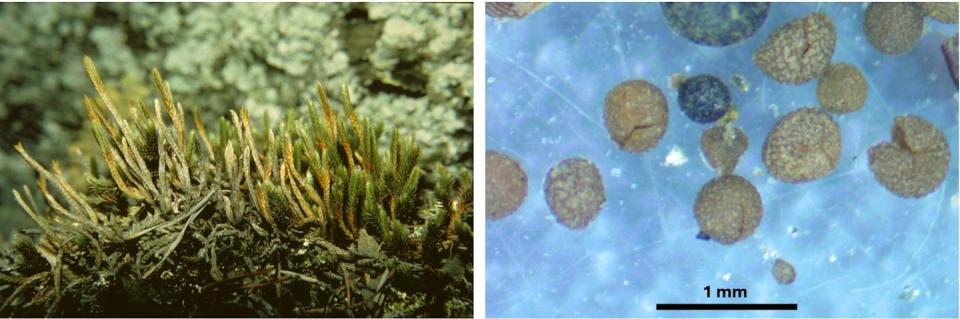

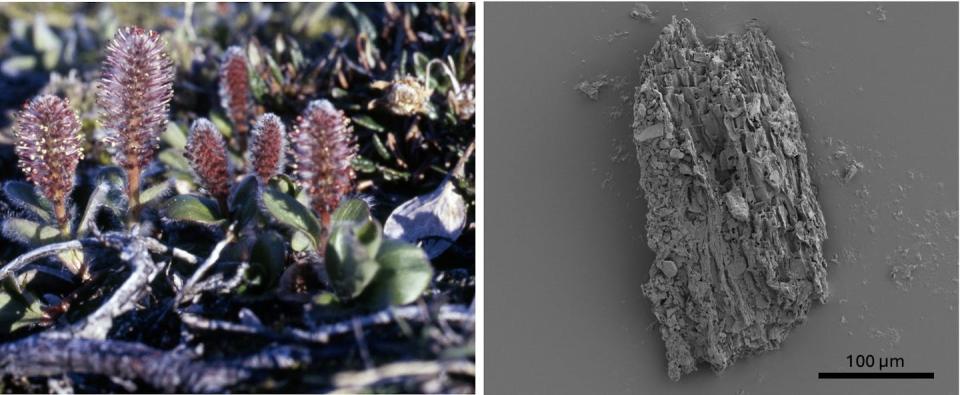

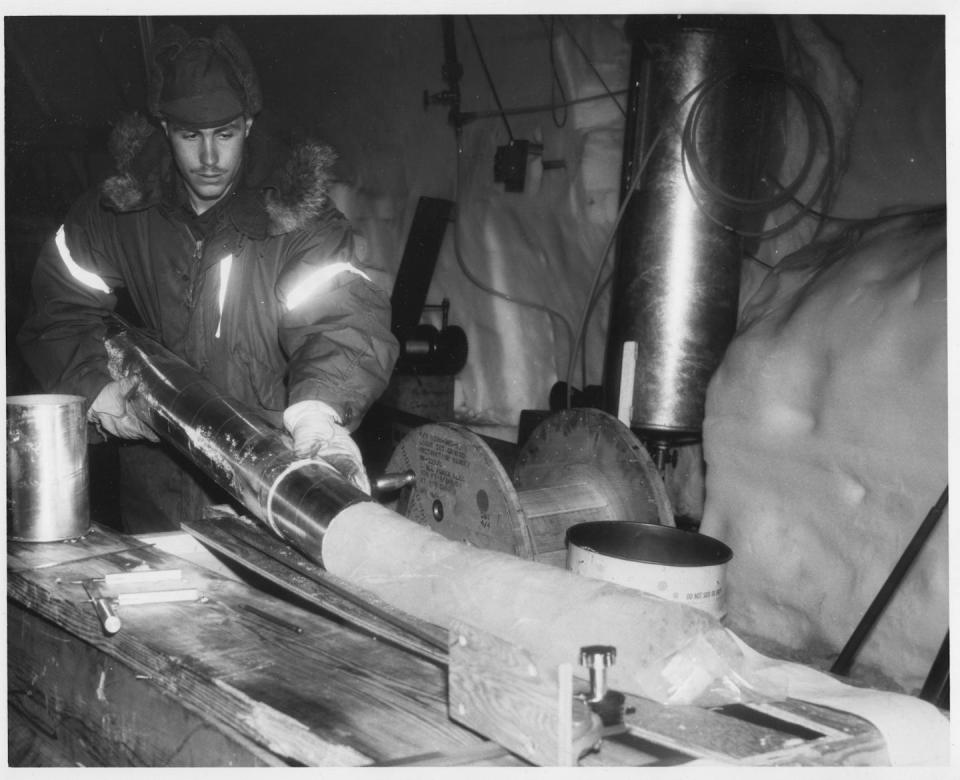

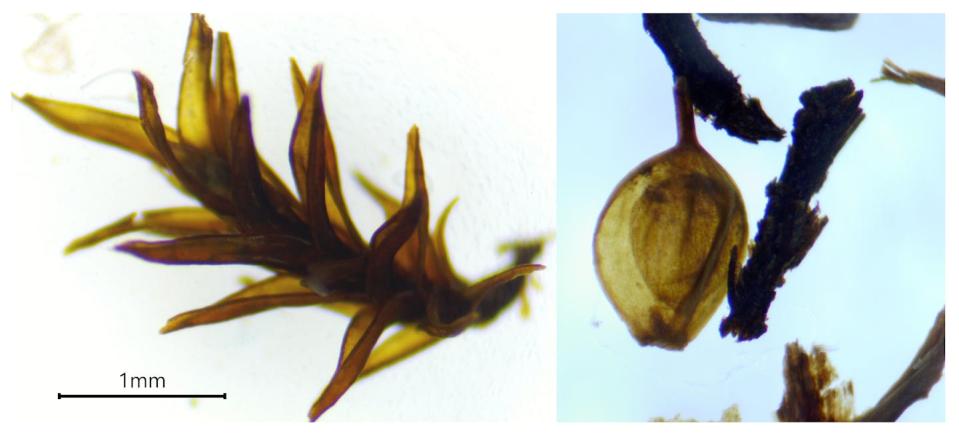

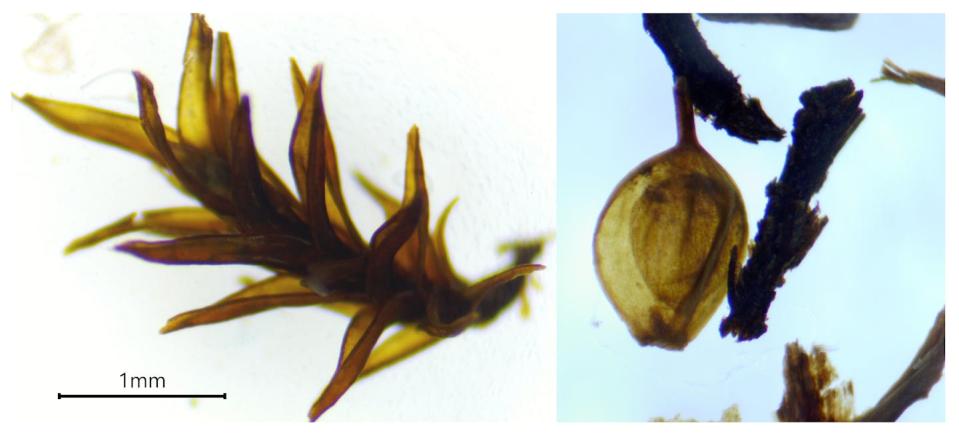

As we focused our microscope on the soil sample for the first time, bits of organic matter emerged: a tiny poppy seed, a compound insect eye, broken willow twigs and spikemoss spores. Dark colored areas produced by soil fungi were the biggest in our opinion.

These were clearly the remnants of an arctic tundra ecosystem – and proof that the entire Greenland ice sheet had disappeared more recently than people realise.

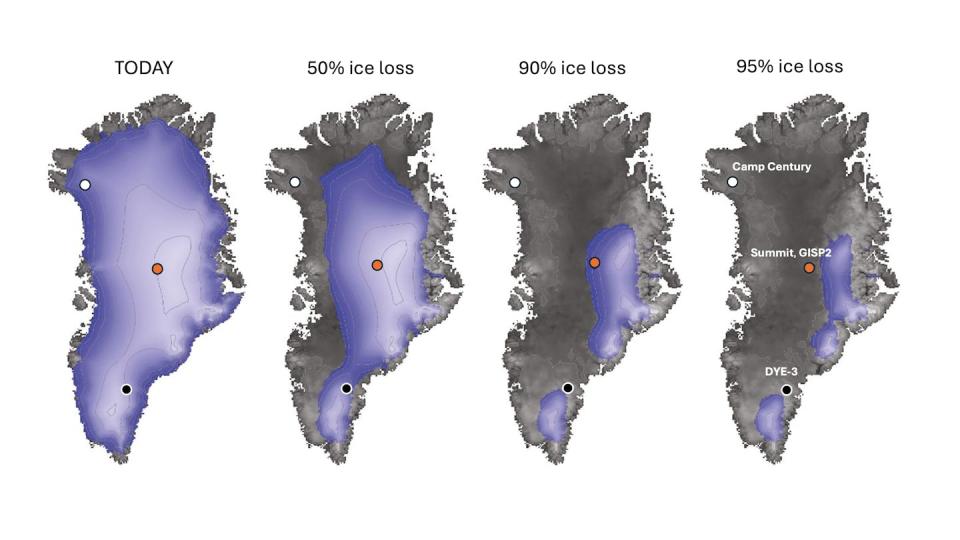

These tiny clues to past life came from an unlikely place – a handful of soil buried under 2 miles of ice beneath the tip of the Greenland ice sheet. Projections for the future melting of the ice sheet are unambiguous: Once the ice at the summit is gone, at least 90% of Greenland’s ice will have melted.

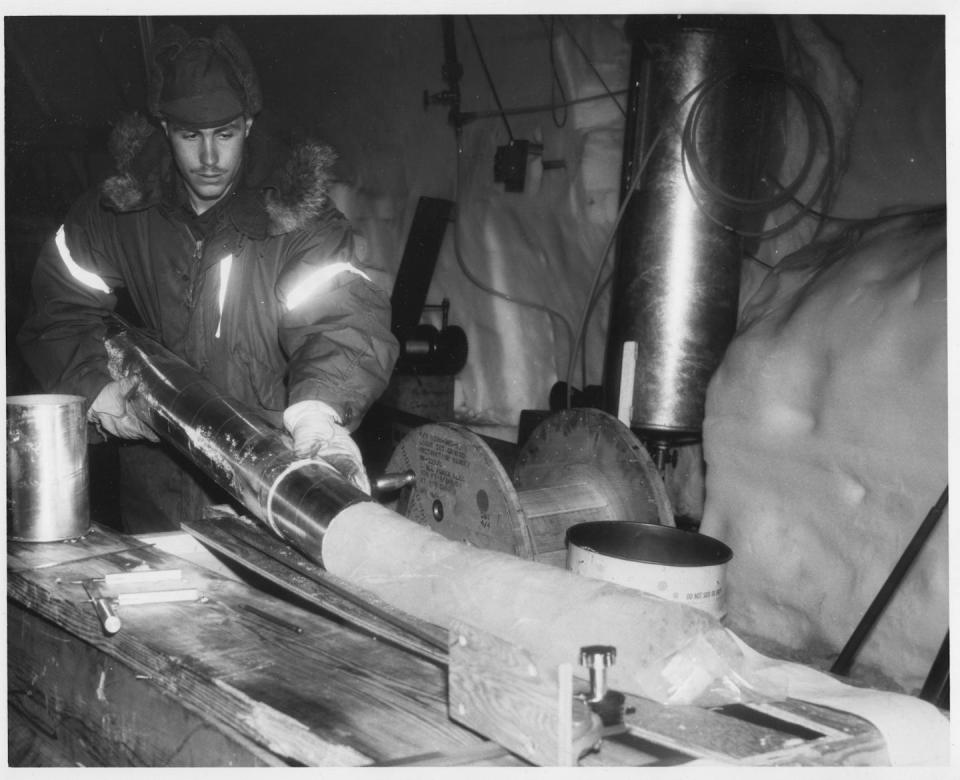

In 1993, drillers at the summit ice core completed the Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2, or GISP2, known as the two-mile time machine. The seeds, twigs, and spores we found came from a few inches of soil at the bottom of that core—soil that had sat dry, untouched for thirty years in a windowless Colorado storage facility.

Our new analysis builds on the work of others who, in the last decade, have abandoned the view that the Greenland ice sheet was continuously present from at least 2.6 million years ago when the Pleistocene ice age began. In 2016, scientists who measured rare isotopes in rock from above and below the GISP2 soil sample used models to suggest that the ice had disappeared at least once in the past 1.1 million years.

Now, by finding well-preserved remains of tundra, we have confirmed that the Greenland ice sheet had indeed melted in the past and that the land beneath had been exposed long enough for soil to form and tundra to grow there. That tells us that the ice sheet is fragile and could melt again.

Landscape with arctic poppies and spikemosses

To the naked eye, the tiny bits of past life cannot be discerned – dark flies, swimming between shiny grains of silt and sand. But, under the microscope, the story they tell is amazing. Together, the seeds, megaspores and insect parts paint a picture of a cold, dry and rocky environment that existed sometime in the past million years.

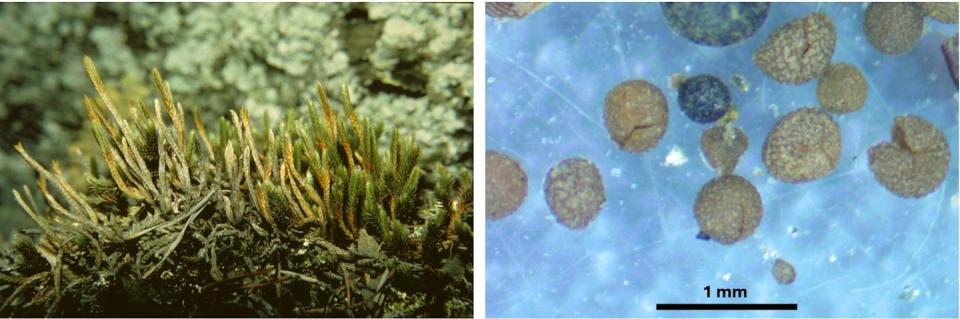

Above ground, Arctic poppies grew among the rocks. Atop each stem of this small but sharp herb, a single clustered flower tracks the Sun across the sky to make the most of each day’s light.

Tiny insects buzzing over mats of small rock spikemoss, crawling across the gravel surface and carrying spores in summer.

In the rocky soil were dark spheres called sclerotia, produced by fungi that combine with plant roots in the soil to help both get the nutrients they need. Nearby, a willow bush has adapted to life in the harsh tundra with fuzzy hair covering its stems.

Each of these living things left clues in that handful of soil – evidence that told us that Greenland ice had once been replaced by a harsh tundra ecosystem.

Greenland ice is fragile

Our findings, published on August 5, 2024, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, show that Greenland ice is at risk of melting at lower concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere than today. Concerns about this vulnerability have prompted scientists to study the ice sheet since the 1950s.

In the 1960s, a team of engineers extracted the world’s first deep ice core at Camp Century, a nuclear-powered Army base built into the ice sheet more than 100 miles off the northwest coast of Greenland. They studied the ice, but had little use for the chunks of rock and soil brought up to the bottom of the core. These were stored and then lost until 2019, when they were rediscovered in a laboratory freezer. Our team was among the scientists called in to analyze them.

In the soil of Camp Century, we also found the remains of plants and insects that were frozen under the ice. Using rare isotopes and luminescence techniques, we were able to date them to a period around 400,000 years ago, when the temperature was similar to today.

Another ice core, DYE-3 from southern Greenland, contained DNA that showed spruce forests covered that part of the island at some point in the past million years.

The biological evidence makes a convincing case for the vulnerability of the Greenland ice sheet. Taken together, the results of the three ice cores can only mean one thing: With the exception of a few mountainous areas to the east, the entire island’s ice must have melted over the past million years.

Lose the ice board

When the Greenland ice is gone, the geography of the world changes – and that’s a problem for humanity.

As the ice sheet melts, sea levels will eventually rise more than 23 feet, flooding coastal cities. Most of Miami will be under water, as will much of Boston, New York, Mumbai and Jakarta.

Today, sea level is rising more than an inch every decade, and in some places, several times faster. By 2100, when today’s children are grandparents, global sea levels will likely be several feet higher.

Using the past to understand the future

The rapid loss of ice is changing the Arctic. Data about past ecosystems, such as we have collected under the Greenland ice sheet, help scientists understand how the ecology of the Arctic will change as the climate evolves.

When temperatures rise, bright white snow melts and ice shrinks, revealing dark rock and soil that absorbs heat from the Sun. The Arctic is getting greener with each passing year, melting the permafrost below and releasing more carbon to warm the planet even more.

Human-caused climate change is on pace to warm the Arctic and Greenland beyond their millions of year-old temperatures. To save the Greenland ice sheet, studies show that the world will have to stop greenhouse gas emissions from its energy systems and reduce carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere.

Understanding the environmental conditions that triggered the last retreat of the ice sheet, and how life on Greenland responded, will be critical to understanding the risks facing the ice sheet and coastal communities around the world. here to measure.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization that brings you reliable facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Paul Bierman, University of Vermont and Halley Mastro, University of Vermont

Read more:

Paul Bierman receives funding from the US National Science Foundation and the Gund Institute for the Environment.

Halley Mastro receives funding from the US National Science Foundation and the Gund Institute for the Environment.